Jayani’s Big Gamble

by Tom Durwood

Part 1 appears in this issue.

conclusion

“One last thing, Jayani,” he said. “Those old ovens are your oasis’ treasure. If you can restore them, all the tribes of the Northern Valleys will seek you out.

“Those main ovens, with shelving, could hold twice as much meat. And ceramics in all the small ones. You can do the delicate work as well as the volume work. Higher margin.”

“To what end?” asked Jayani. “Zrimat keeps it all.”

“It doesn’t have to be that way.” He explained his idea. He said it works well among the Ottomans, and in the larger villages, those with Western ways. “You can charge well for such work. Enough for the British surgeon. But first you need to calibrate the volumes. Those volumes interior to each separate oven. With accuracy. If you lose control over the volumes, if the heat becomes uneven”

“But how can I measure those spaces?” Jayani asked. “They are irregular.”

“They are varied,” the Arab corrected. “Each has a dimension that can be calculated and recorded. The contours follow specific shapes. You’ll see.” He took out paper from a satchel the servant carried. He drew on it.

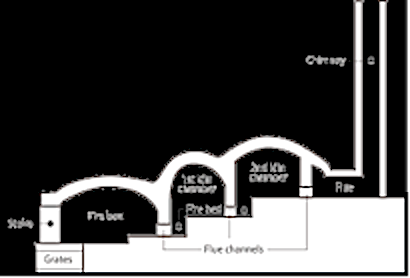

Here is what he drew:

4. A Proposal

Without mathematics, there’s nothing you can do.

Everything around you is mathematics.

Everything around you is numbers.

— Shakuntala Devi

“Did you say you wish to rent the ovens?” asked the Council Chief, Ajmal.

Ajmal did not sound angry, or surprised, she sounded like she wanted clarity. Ajmal was a stout woman, tall, solid, big-shouldered and sharp-eyed.

“At night?” asked another of the Council. “Is that what you said?”

“Yes, Elder,” said Jayani. “I propose to rent the ovens each night. For a fortnight.”

“What hours?” asked Amjal.

“Midnight to dawn,” replied the girl Jayani.

The evening sun was low on the horizon. The Council fire burnt steadily.

“What price can you offer, dear?” asked Ajmal.

“Five hens. Two roosters. And two bushels of rice.”

“So much?” asked the stablemaster. “Quite a gamble...”

Not with the Venetian gauge, Jayani wanted to say, in response.

“This gambit is all for your Aunt,” said Saraya, the seamstress. “This is for the doctors’ fees.”

Jayani made no reply.

“I know those ovens,” continued the girl, at length. “And my proposal is an honest one. Well this serves the qabila,” she declared.

She was smart to use this phrase, much beloved among the Ahichhatra, a phrase that might translate today to “the common good.”

Hands akimbo, Jayani spoke no further. She had taken the Arab’s idea to challenge the village Elders, betting on her own talents, putting the Council in a perfect position: profit without risk. All of the risk was now Jayani’s to bear.

The slender figure stood, silhouetted against the full moon.

Along the perimeter, near the watchtowers, a pair of donkeys brayed in some nocturnal episode among the livestock. One of the older cows lowed. Was that a camel, snickering?

“Such an arrangement is without precedent,” protested Zrimat. “Besides, the ovens need to recover at night. The... the mortar can become fatigued. It is well-known that the clay and mortar... can get fallow.”

“No, it isn’t! It isn’t ‘well-known’ at all!” called the terrace-slope farmers, who despised Zrimat. “You just made that up!”

There followed a lively discussion.

Jayani was asked to wait by the ovens.

The Council voted.

She was called back.

“The Council grants your request, young lady,” said Amjal. “Starting Saturday. The payment is due Friday noon.

“We ask that you donate half the profits of this enterprise, if it is such, to the village. It will go toward stone improvements around the springs.”

The fire crackled.

“Agreed,” replied Jayani.

5. Experiments With the Various Kilns:

Volumes of a Tandoor

Mathematics, for all its abstractions,

is a communal and human activity.

— Eugenia Chang

“Those missing shelves,” said the mason, a Samanid man as thin as a shadow. He had stopped on his way from the quarries and rested his brimming wheel-barrow to regard the oven banks. He had not spoken for some time.

“They’re for cakes.”

This remark changed everything.

“Here.” He pointed a long index finger. He pointed to the rusted, dust-covered hinges along the upper walls on either side of the open furnace, and the long metal supports, unused for many years.

Dark-eyed Jayani knew exactly where he was looking. She carefully closed the stove doors and opened them again.

Jayani had long imagined an upper section to the much-used meat kilns, a sort of internal balcony. Such an addition to the ovens’ capacity would dramatically increase their output. A boon to her productivity. She would have to make sure the heat patterns were unchanged... But it could not be regulated.

“I saw the furnaces at Sunak,” continued the mason. “There, the bakers shunted the excess heat of the big stacks in ways so as to fire the confection ovens. Like overflow,” he added, “like a dam.”

“It is well considered, artisan,” said the mason to Jayani as he bent and raised his stone-filled wheelbarrow once more. “You will solve the problem, of that I am sure. May the coral-crowned Queens of Khurasan guide you.”

Jayani was already drawing a new configuration based on his suggestion — she could amend the Venetian device — and only managed to shout her thanks when he was almost out of sight.

He heard, and waved.

* * *

A fully-grown camel weighs 1300 pounds.

A camel can drink two hundred liters of water in three minutes.

A camel has a third, transparent eyelid that serves to dislodge dust from its eyes.

Most livestock lose 20 to 40 liters of water per day. Camels lose a mere 1.3 liters of fluids every day.

That evening, Jayani and Third Aunt and one of the mother camels watched from their porch as the calf Al-Layth ibn Al-Saffar attempted to lie down for her rest.

Tentatively, the very young beast bent one knee. She stood back up, dissatisfied with the knee-bend. After several tries, she managed to get a front knee solidly planted on the ground. She quickly followed it with a second knee.

Then the back legs lowered, and her full weight fell. Finally, the calf rested her neck and head on the ground, legs folded neatly under the torso. Huh.

Everything in its place, thought Jayani. Just so...

* * *

“Do you mean tasbih?” asked Saraya, the seamstress, coming down sharply on that last word, for that would have meant something.

“No, not tasbih,” replied Jayani. She had not brought the topic up in the first place, and cared not to explain it, nor to show how much she knew. “Like tasbih, but not the same.”

Jayani stoked one of a small bank of clay ovens. She shut the chamber doors. She deftly checked the temperature at either end, and on the top and bottom. She made careful notations.

“Then what?” asked the woman. “This divination must come from somewhere.”

“Geometry,” said Jayani.

“And is that the Arabic system? Is it that which the Pharaohs used?”

Jayani nodded that it was, indeed.

“Ah!” said Saraya. She nodded, satisfied. Everyone needs to understand.

* * *

“See this?” Jayani asked Ganesh. She held up the door of a cylindrical stove.

It had taken nine hours to disassemble and clean and reassemble the various ovens in the wall of kilns. Jayani had paid two of the young shepherds to help.

“We have to find out how much it holds.”

“Can’t we just look at it and tell?” asked little brother.

“No, we can’t just guess. We need to know for sure. We need to know exactly. So all we do is measure the width, the length, and the height. Now multiply these three.” Volume.

“And when we have an irregular shape within the box, we simply subtract its volume... like so.”

Ganesh nodded, satisfied at the process. “What do you mean ‘multiply’?” he asked, after a minute.

Several times, when Ganesh and Third Aunt were asleep, Jayani explained her tables to the camel calf, Al-Layth ibn Al-Saffar.

Al-Layth ibn Al-Saffar was well pleased, nodding and chewing as the girl spoke, letting the stream of murmured words splash over her.

The camel calf seemed to favor simple addition and subtraction, and tended to ignore anything to do with multiplication or geometry. She sought to spit on the tablet and abacus whenever Jayani brought up triangles.

* * *

Calculating Kiln Volume

1. Volume of a sprung-arch kiln: Volume = Width x Depth x (height of the side wall + 2/3 of the rise)

2. Volume of a catenary kiln: Volume = Depth x Arch Area (4/3 height x 1/2 base width)

* * *

Late that evening, one of the camels, a popular female named Eshanamaaz, brayed, asking to be let out, back into the pastures, to graze some more.

“Because you’re so special, is that it?” called Jayani.

The air was rich with odors of meats stewing at a low flame, stewing overnight, and smoke from the fires in the lookout towers.

“Request denied. Go to sleep.”

6. A Gamble Pays Off

These things tend to escalate.

— Julian Broudy

Word spread in the countryside.

Travelers along the northern highway of Uttarapatha took a growing interest in the girl Jayani and her ovens. The bold gamble she had taken intrigued pilgrims and camel-drivers, always eager for a good story. At various times of day, all manner of the curious crowded the tandoor, the communal ovens of the oasis called Ahichhatra.

The onlookers took pleasure when a Turkish tea set emerged from one of the European stoves in a molten lump. Such a thing!

They inquired respectfully about the mathematics, and the designs and distinctions and capacities among the many ovens and kilns, until Jayani took to locking the gate to the tandoor compound. Too many distractions and she would ruin a necklace, or an urn, or a slab of precious fragrant meat in the broiler.

Jewelry emerged from the kilns of Ahichhatra, running day and night, and slabs of mutton, roasted grain, smelted silver, and more.

Her constant experimentations with charts and volume and equations gave rise to improvements, with Jayani moving things here and there, making adjustments. Each was noted by the onlookers. She developed a team of boy porters to carry merchandise to and from the ovens down the foot paths to the Bakhari Road with its many caravans and wagons and travelers.

An elderly apothecary came to her with minutely detailed instructions for simmering certain custom-brewed medicines. A family of toolmakers came over the Sijara with curved blades for swords.

So many customers. So much money. Would it be enough to pay for the English doctor? She had heard tales of such transactions going wrong.

Official agents of the Achaemenid asked her to mint a batch of the gold quarter svana coins, and the small, square bronze purana, as well as die-struck saurashta, the face of which caused some uproar among the Gandhara veterans who craned their necks to see.

* * *

“We forgot to calculate the differences in slope,” concluded Jayani one afternoon. This realization was followed by a string of oaths.

Only the camel calf they had named Al-Layth ibn Al-Saffar, who had taken to following Jayani everywhere, was there to hear.

“It is a mistake we can correct, loyal one,” Jayani told the young camel, once she had calmed down.

If she had been worried, the young camel gave no sign of it, but continued to work her jaws unevenly on a wad of grass as she stood patiently, close by her companion, the girl Jayani.

7. Conclusion

The power of pure thought has shaped

our world for over two millennia.

— Jim Al-Kahlili

Three days later, the English surgeon Beekman arrived with the Persian caravan. He brought two wagons and full regalia.

A big-boned red-headed storm of a man, Beekman shook Jayani’s hand with both of his. “Salim Abdallah al-Ayyashi told me to do my best work for you,” Beekman told her with a smile. “Now where is the patient, my girl?”

Jayani took him to meet Third Aunt. He peppered her with specific questions about the nature and angle of the camel’s fall, her numbness, and more.

Jayani paid the fee, in full, in advance.

The crew of English nurses and workers set about busily striking medical equipment from the wagons. Within an hour, they had constructed a tent hospital on the sandstone plaza by the springs, complete with operating table, reflectors, medical charts, and arrays of glass-vialed antiseptics everywhere. Obsessed with germs, two nurses mounted drips alongside the reflectors, air pumps, and basins of bright-smelling quinine.

The surgery began.

* * *

Ahichhatra’s villagers crowded around the hospital tent. One of the shepherds’ wives narrated, giving her interpretation of events, eliciting reactions at each incision.

The operation seemed to take forever.

The red-headed doctor emerged from the tent flaps. “The hip broke fairly cleanly,” he told Jayani, “limited shattering. So some luck there. I cleaned out the shards, that’s what took time. They would certainly have become infected soon, and then it would be too late. I’ve lined up the bones properly and pinned the hip-pieces in place with screws and rods.

“She’ll need rest, quiet, plenty of greens, and as much dairy as she’ll eat. You have cows, yes?

“Yes, janaba,” answered Jayani. “And her spine?”

“A bad bruise, no more,” replied the Englishman. “No damaged disc, no broken vertebrae. We were prepared to do a laminectomy, but that would have been pointless, of course. No, no complications. Spine intact. Hip cleaned out and repaired. She may limp, but the joint is well repaired.”

The Englishman glanced at the shepherd’s wife, who was listening and translating her version of his words to the assemblage.

“You have saved her life, young lady,” concluded Beekman.

“No better care could you have gotten her, East or West,” added one of the nurses as she handed Jayani a large menthol-smelling basket of ointments, soaps, bandage dressings, salves for the recovering patient and liniment for Jayani’s hands.

* * *

The villagers gathered in the plaza, also placing prepared food on tables outside their homes.

“It seems,” commented Amjal, “that our Jayani’s little gamble has paid off.”

“Mine and mine alone,” an angry Jayani retorted. “Did a single neighbor offer to loan so much a rupee for the Englishman’s fee? To save Cyra’s life?” She rubbed the liniments on her hands and forearms and wrists.

But all knew about Jayani’s gamble, and the girl’s hard work. All of the oasis community of Ahichhatra understood. Besides, the oasis village had gained much. The Council had used their quarter-share of Jayani’s rental income to clean and dredge the springs, and make a proper waterworks, like the one at the oasis of Taklamakan, with connecting ponds and basins and waterfalls. Masons installed a new, level patio of big quarry stones around the springs.

* * *

New plantings appeared along the northern slopes.

When the six-month rotations were announced, Jayani had been promoted two stations higher, to Master Baker.

Zrimat was rotated to Assistant Sweeper of the Stables.

Third Aunt slept in a cushioned bed, in a house now with four rooms and new, high kitchen counters. She used crutches, then a cane to walk the yard and to make her rounds to the markets. With the money left over from the English surgeon’s fee, Jayani funded a dowry for Third Aunt. A tall young terrace farmer had been keeping company with Cyra, more and more. He had helped the thatcher install a new roof.

Jayani bought the hut from Bhagat.

Jayani hired a mathematics tutor for Ganesh. She told her brother that he, too, would pull the weight soon.

She designed a new bank of ovens. She began saving for her own dowry. She spent time tending the camels whenever she could. She called them each by name, giving special care to young, sheepish Dakshinapatha. Jayani chastised the camels for their wickedness, yet enjoying their dark humor.

And each night, the recumbent camels slept smiling beneath a platter of stars, dreaming of coral-crowned queens in blue oceans.

Copyright © 2025 by Tom Durwood