Lost Gold Rush Towns

of Sacramento

excerpt: Eric Webb, “Prairie City”

Lost Gold Rush Towns of Sacramento Publisher: The History Press and Arcadia Publishing Date: March 4, 2025 by Special Collections of the Sacramento Public Library ISBN: 9781467151139 Footnotes (in a new window) |

Prairie City

“Prairie City” is an excerpt from the book Lost Gold Rush Towns of Sacramento released by History Press on behalf of the Sacramento Public Library. Primary sources include contempora- neous accounts from newspapers such as the Sacramento Union, Sacramento Bee and the Folsom Telegraph as well as the John Plimpton Collection housed at the California State Parks headquarters in Sacramento.

* * *

On November 5th, during California’s centennial year of 1950, a crowd of three hundred people gathered at the presumed site of Prairie City. Surrounded by a vast oak woodland savanna, without a remnant of the old town to be found, citizens traveled from throughout Northern California to pay their respects. A plaque embossed onto granite rock, designated as Department of Natural Resources marker number 464, was positioned just north of the corner of Prairie City Road and the new federal highway 50.394

Sacramento County executive Charles Deterding and supervisor Ancil Hoffman attended the Sunday afternoon affair, but the stars of the show were former residents and their family members. The Native Daughters of the Golden West, in a thoughtful gesture, provided a visitor book, which collected reminiscences of the distant past. “Prairie City is my birthplace,” exclaimed Anthony Perry, who drove in from Alameda. Louise Fleming, from nearby Folsom, added, “My folks were married here May 12, 1856 by H. F. Kellum, justice of the peace.”395

Elizabeth Miller played show and tell. She unveiled a locket, made of gold mined at Rhodes Diggings, just a half-mile away. The keepsake was passed down from her great-uncle, Lewis Tomlinson. “He had the locket made in 1850 and presented it to the girl who became his bride in 1854. It contains a daguerreotype of him and on the inside of the cover is engraved ‘Lewis to Alta’. Mr. Tomlinson died in 1869. He and his brother Abelard are buried in the citizens cemetery there.”396 Little did the attendees know, as was discovered a half century later, they stood amongst Lewis, Abelard and their Prairie City ancestors.

Dr. Len Kidder standing at the site of Prairie City cemetery in 1938.

Center for Sacramento History

Prairie City, founded in 1853, catapulted immediately into prominence. In the 1856 election, it featured the largest county voting precinct outside the city of Sacramento. By 1860, however, the village was in serious decline and was ultimately degazetted from local maps in 1883.397 Unlike its neighbors, Mormon Island and Negro Hill, which had residents and structures attesting to its existence, Prairie City’s foundations disintegrated into the soil. For many years, not a trace could be found.

Prior to 1853, miners in the region could only employ their techniques in shallow deposits during the rainy season. At first, Kelly’s canal routed water from Alder Creek to the mining operations at the future town site.398 Alexander McKay and his cadre of laborers, many of them Chinese immigrants, built a canal originating in New York Ravine along the south fork of the American River which begat a web of aqueducts that not only reached Mormon Island, but other mining locales including Prairie City.399 In a dramatic turn of events, McKay sold the canal and “all the Dams, Branches, Aqueducts and all the rights, interests, privileges, and advantages to the possession thereof” to the “Natoma Water and Mining Company (NMWC) and to their successors and assigns forever.” The parties executed the sale on November 4th, 1853 with McKay receiving a relatively small sum of $500.400

In another happenstance of history, McKay and the Natoma Company initially planned to terminate their ditch at Rhoads Diggings which was located approximately one mile east of Prairie City. They opted, however, to continue the canal another mile to the west in order to connect to Alder Creek. When ditched water reached the area during the summer of 1853 year-round mining was assured and the town was born. The NMWC monopolized water supply ingeniously by recycling water used by local miners only to charge them once again for the commodity. Not only did the company guarantee delivery during the summer months they assured themselves an endless supply of profits.401

According to an 1880 account from Thompson and West, Prairie City became an important regional “business town” or supply center which served the nearby mining camps such as “Rhodes Diggings, Willow Hill Diggings and Alder Creek.”402 Water use ledgers of the Natoma Company as well as the 1857 tax rolls of the Sacramento County Assessor’s office indicated at least “thirty families, a few hundred miners” as well as 27 other individuals in the township.403 Beyond that, contemporaneous estimates varied but nonetheless accounted for a large population. In April of 1854 the Sacramento (Pictorial) Union insisted that “the population of Prairie City and vicinity embraces about 2000.”404 Thompson and West simultaneously pegged the population of Prairie City at one thousand.405

The term “vicinity,” used by the Sacramento Union may be an important distinction as it most likely accounted for the surrounding mining camps. This may have included the mysterious village of “Ragtown” located one mile east of Prairie City.406 Permanent structures, typically made of wood or stone, were a defining characteristic of the mid-nineteenth century California township. Although scant references to this locale exist, Sacramento County assessor documents from 1857 list a man by the name of J. Southworth who was taxed $20 on personal belongings as well as $100 on improvements, “indicating that he was probably living in a shelter.” More convincingly, Charles Uhlmeyer’s residence was simply listed in the county records as being in “Ragtown-one mile east of Prairie City.” Otherwise, the fugacious Ragtown never made it to a map, it may have simply “boom and busted” before any cartographer bothered to notice.

Although canvas structures undoubtedly dotted the landscape, Prairie City was more than a “tent city.” The lithograph of a woodcut, featured in the New Year’s Day 1855 edition of the Sacramento Daily Union offers insights into the substantiality of Prairie City. Aside from the main street with its wagon cut tracks, two rows of one-story wooden shops can be discerned receding into the background. The woodcut, drawn with “photographic perspective,” highlights the store fronts with accuracy. Adams and Company as well as its competitor, Wells Fargo Express, were common occupants in California mining towns providing agents “in every considerable mining camp.” “M. Beach and Company Clothing,” “Queen City,” and a generic “Drug Store” bolstered the cityscape. Two doctors set up their practices as well as an additional six shopkeepers.407

The Sacramento Daily Union noted in June 1853 that two square miles surrounding the “Prairie Surface Diggings,” discovered previously in May of 1852, had now been claimed in anticipation of the ditch. Forty canvas and wood frame buildings immediately popped up with lots going for $100 to $200 each. The next month, in July, claims spoked around the township in a three-mile radius.408 Within a two month span the population ballooned to 1,500 that included fifteen families “containing ladies and children.” Twenty by sixty foot “corner lots were selling for $500.”409

Although Dr. Y.A. Massie built the first structure, a hotel; a single carpenter, Elisha Waterman, “erected most of the buildings” in Prairie City. He clearly employed a lot of workers “because, by July 1853, the town is said to have been comprised of 100 buildings, including 15 stores and 10 boarding houses and hotels.”410 Among the enterprises, Jesse Dresser’s saloon stood as a favorite watering hole as well as “the largest general merchandise store” which was opened in 1854 by the brothers John and James Spruance.411 “Two lines of stages were running daily” connecting the town with Sacramento as well as its sister mining towns in Mormon Island and Negro Hill. One of the stage lines, operated by Rablin and Company Express, offered connections from Sacramento, originating from 2nd and K streets at 7am on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, with return trips on Monday, Wednesday and Friday.412

In a letter to the Sacramento Union, a local miner described the preferable conditions of Prairie City:

Miners from the northern region are daily crowding in upon us, and tell us that many more are coming, and that as soon as those who are in the rivers are driven out by the rain, they will come down from the mountains into these regions, where the mines are equally as good-if not better-and provisions much cheaper. They say the immense suffering and hardships they underwent last winter is a dread upon them, and they are determined to seek more comfortable quarters for the approaching season.”413

Prairie City, just as in Negro Hill, included a vibrant Chinatown. In the April 1854 edition of the Sacramento Pictorial Union Prairie City became “a favorite resort for Chinese men, large numbers of whom have taken up their residence in the neighborhood and work the refuse portions of the ground with much assiduity.”414

Yet almost as quickly as Prairie City blossomed, it promptly withered away. The slackening of the town can be closely correlated to the exhaustion of surface gold throughout California. California gold production peaked at just over $81 million in 1852, leveled out at $70 million in 1853 plummeting to just under $46 million in 1859. The 1860s saw a further decline with totals just over $23 million in 1863 and bottoming out at $17 million in 1866.415

Chinese immigrants, already a significant presence in the Prairie City community, increased their majorities in the local labor force as the town disintegrated. In 1854, Natoma Company water ledgers accounted for 176 miners, a somewhat misleading number given that at least 60 of these “miners” were actually mining “companies” in and of themselves. By 1866, the NMWC listed only 48 names, none of which included any other mining companies, another indication of their evolution as a monopoly. Of these 48, 34 “are Asian names, plainly indicating the presence of Chinese in the area after many of the original miners, representing several ethnic groups but mostly of European extraction, had left.”416 An 1869 description of the region maintains “that not more than 500 miners were taking water from the Natoma Ditch to wash placer gold at Red Bank, Mormon Island, Willow springs, Rhodes Diggings, Texas Hill, Alder Creek, Rebel Hill, Tates Flat and Prairie City.” All except Red Bank and Mormon Island were within a three-mile radius of Prairie City.417

In the 1853 election, 364 voters turned out with votes cast dropping in the next two years to 235 and 183. This “special” plebiscite on March 28th, 1855, resulted in an objection to the formation of the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors. The local election, overseen by Justice of the Peace H.F. Kellum, also appointed Alexander McKay to the school commission, perhaps in consolation for his sale of the New York Ravine canal.418

But the decline in voter rolls offered further evidence of Prairie City’s diminution. In the presidential election of 1856, 213 cast their ballot at the main hotel, the Marble Hall, with the majority supporting James Buchanan over the first National Republican party candidate, John Fremont. Turnout dropped to 115 in 1857 even though “the city” was the “principal place for what was then called Granite Township.” In 1860, after two years of dwindling voter participation, one hundred citizens stuffed the ballot box with 15 filled out in favor of Abraham Lincoln.

Seventy-eight voted in the 1863 election, then 50 in 1864. Prairie City was clearly a Democratic town with only 14 voters favoring Lincoln over George McClellan. After the 1864 election, the voting precinct disappeared. What once had been the second largest election center in Sacramento County simply vanished.419

Geography contributed to Prairie City’s downfall. The town was equidistant from Coloma Road to the north and the Sacramento-Placerville Road to the south. Unlike Mormon Island and Negro Hill, Prairie City was not situated near perpetual water, rather it was entirely dependent on the Natoma Ditch with nearby Alder Creek merely a seasonal stream. By 1856, Folsom not only had river and road access but overtook neighboring towns as the terminus of the Sacramento Valley Railroad.

An automobile crosses Alder Creek at Prairie City in 1938.

The cemetery is on the hill at the upper left. Center for Sacramento History

As placer gold disappeared, people moved on from Prairie City. Frank McNamee, who emigrated from Cavan County Ireland, resided and mined in Prairie City for three years before moving to Folsom in 1857. Taking advantage of the new railroad, he opened a mercantile store, overseeing it well into the 1880s whereupon his wife took over. By 1876, “there was nothing but a school building,” which was later relocated, and “the ruins of an old livery stable and one cabin, where some miners live.”420

In the January 7, 1906 edition, the Folsom correspondent for the Sacramento Union composed an elegy for Prairie City:

Prairie City was located a few miles south of Folsom, on the road to Michigan Bar, but if any of the men who dug gold dust about there and who used to sell their dust in the busy town were to return after the lapse of fifty-five years that have intervened, it would puzzle them to point out the spot where Prairie City stood, with its streets, its stores and hotels, for there has not for many long years been a vestige of the place to be seen. Instead of the red-shirted and high-booted miners, the only denizens of the gulch have been cows, jack-rabbits and coyotes. Where merchants at one time did a thriving business, and the rattle of stage wheels were heard all the day through, the solitude is broken now only by the occasional shot from some quail hunter’s gun, the tinkle of cowbells, and the doleful nocturnal yelp of the coyote...

Some twenty years ago an old stage driver who still pilots a mud wagon through that locality on its tri-weekly trip to the Cosumnes, used to call the attention of his passengers to a little heap of stones, which he said was once a part of the foundation of a building that at one time was a Prairie City hotel. Now even that little pile of stones has toppled over, and the old stage driver’s trips have ceased. He too, has disappeared from the earth as completely as had the Prairie City of other days.

Intensive gold mining cannibalized the Prairie City town site. As bucket line dredging and other innovations took hold at the turn of century the Natoma Company employed laborers that consisted of an increasing percentage of Chinese immigrants. Archaeologists have encountered numerous sites in the area, discerning locations inhabited by both European American and Chinese Americans.

Perhaps the most compelling of these sites is what California Department of Transportation archaeologists refer to as “Locus 29.” Currently situated beneath Highway 50 one mile east of the Prairie City interchange, this may have, at first, been the site of Ragtown. Not long after, Locus 29 encompassed living spaces for local laborers. Anthropologists documented a segregated neighborhood along a tributary of Alder Creek: “Of particular interest at this site is the fact that rock hearths and Chinese artifacts were found only on the west side of the drainage. To the east were no Chinese materials or features, only Euro-American artifacts and rectangular, rock-supported features and pads identified.”421

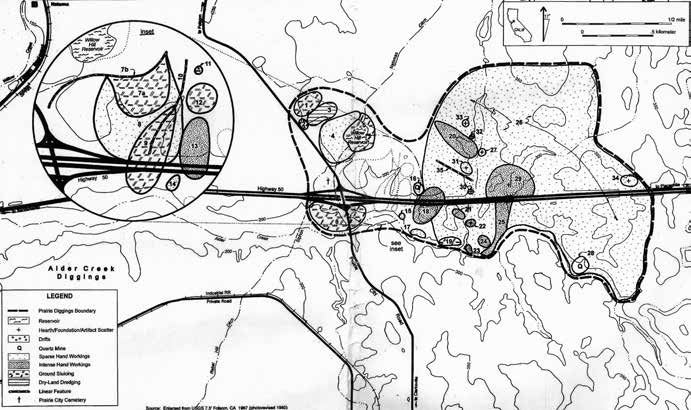

A map of the Prairie City region. Of particular note is Locus 29.

The cross at the interchange indicates the cemetery.

California Department of Transportation

Chinese American laborers also resided in barracks provided by the Natoma Company. one of which was located in Blue Ravine, near the current intersection with Folsom Boulevard, as well as Willow Creek nearby. They would then travel to the mining sites on a daily basis.422

In the 1940s, a decade prior to the centennial celebrations, workers paving the new U.S. Highway 50 uncovered shards of headstones. But no real effort was made to locate the Prairie City cemetery. The workers merely reburied what they found.423

A half century later in the 1990s and armed with the National Historic Preservation Act, archaeologists initiated a more concerted effort to locate the cemetery as Caltrans constructed the new Prairie City Road-U.S. 50 interchange. Historians and scientists now had even more evidence in their dossier. Maps from the 1860s suggested that the proposed interchange laid directly on top of the erstwhile township with the cemetery on “top of a knoll in the northwest quadrant of the interchange.” Using remote sensing technology and mechanical equipment, archaeologists formally exhumed twelve Prairie City residents and promptly transported their remains to the Caltrans pathology laboratory. Of the twelve, anthropologists identified seven adults and five children.424

Upon the construction of the freeway interchange in 1997, “thirteen fragments from marble headstones and three granite headstone bases” were found buried underneath the surface, none of which “appeared to be in its original location.” One of the granite bases was uprooted by a tree, otherwise the fragments, all from disparate headstones may have been “buried together as a sign of respect.” Mabel Brown, whose ranchland encompassed the knoll that housed the cemetery, “found and reburied several headstones from the cemetery” during highway construction in the 1940s.425

Dr. Kidder standing next to a headstone at the cemetery in 1938.

Center for Sacramento History

As archaeologists excavated the cemetery in preparation for the construction of the Prairie City Road interchange, they discerned a similar design in the headstones. All of the fragments contained images of flowers, with one piece featuring a representation of a weeping willow, common Romantic-era motifs in nineteenth-century graveyards. Although the headstones derived from the same type of marble, their edges and thickness were different. Presumably, the markers were manufactured locally but they differed in design from cemeteries in Folsom and Sacramento, perhaps indicating their origin in the 1850s when gravestones were somewhat less homogenous. As for the inhabitants of the Prairie City cemetery, a vast majority of their identities remain a mystery. Decades-old headstone fragments offer few clues and cannot be reconstructed to provide any names.426

Death notices, however, from local papers and from Trinity Episcopal Church in Folsom deliver better results. Some of those who died at Prairie City included William Gunn, Catherine Gertrude Turner, Warren Morse, George Elmond, Julia Theresa Bremond and an infant with the surname McKarnan. Most of these people died between 1853 and 1858 and it is not known whether these residents were reunited with other family members or perhaps buried in Folsom, Sacramento or elsewhere. A small number of townspeople were buried in the cemetery in subsequent decades with the last interment most likely G.W. Mayberry, “who died at this home, described as Prairie City, in 1898.” Many of the deceased were undoubtedly miners, but others may have been involved with the numerous saloons, stores and various enterprises within the city.427

Evidence strongly indicates the presence of members of the O’Hara family in the Prairie City cemetery. Berniece Timnbelake, her testimony substantiated by records from Trinity Episcopal Church and local newspapers, was the granddaughter of Margaret Ellen O’Hara, who was born in Prairie City in 1863, the youngest of four children. Margaret Ellen’s parents, Michael O’Hara and Mary O’Hara (Donnelly) arrived from Ireland sometime in 1853 to try their luck as gold miners. Aside from Margaret Ellen, the other three O’Hara children were Mary, Annie and James.

Tragedy struck the O’Hara family in rapid succession. The lone son, James, died at nearby Rhodes Diggings on January 13th, 1870. Just a few weeks later, his father, Michael, died at the age of 45. His widow, Mary, remarried and left town, but was promptly abandoned by her new husband and returned to Prairie City in 1872. She would die shortly thereafter. One of the three daughters, Annie, died at the age of fourteen sometime in the early 1870s. All four members of the O’Hara family are presumed to be interred at the Prairie City cemetery.

The O’Hara descendants became prominent figures in Folsom. Margaret Ellen would later marry another Irishman, Tom Foley in 1880. After fighting for the Union in the Civil War, he spent his later career as a guard at Folsom Prison. Other extended relatives enjoyed significant positions in local water businesses; Will Rowlands was a dredge master for the Natomas Company and Charles Goulden worked as a carpenter for the Capital Dredge Company in the early twentieth century.428

George Crooks was another well-known inhabitant during Prairie City’s most vibrant timeframe between 1853 and 1855. According to California State Parks historian John Plimpton:

Crooks was originally from Scotland, where his name was spelled “Cruicks.” Trained in his home country as a carpenter and cabinet maker, he was 28 when he arrived in Prairie City to try his hand at mining; he worked with two partners. While there, he and his wife had a son, who soon died, and a daughter. Crooks’ success as a miner was not spectacular and in 1855 he managed to find work as a carpenter helping to repair the Natoma Company’s long flume over New York Ravine, south of Salmon Falls. Crooks secured a position in the Natoma Company as a water agent and foreman in 1857, a job he would maintain until his retirement 43 years later.429

Conclusion

In the Sacramento Union’s January 7, 1906 edition, the Folsom correspondent composed an elegy for Prairie City:

Prairie City was located a few miles south of Folsom, on the road to Michigan Bar, but if any of the men who dug gold dust about there and who used to sell their dust in the busy town were to return after the lapse of fifty-five years that have intervened, it would puzzle them to point out the spot where Prairie City stood, with its streets, its stores and hotels, for there has not for many long years been a vestige of the place to be seen. Instead of the red-shirted and high-booted miners, the only denizens of the gulch Lost Gold Rush Towns of Sacramento have been cows, jack-rabbits and coyotes. Where merchants at one time did a thriving business, and the rattle of stage wheels were heard all the day through, the solitude is broken now only by the occasional shot from some quail hunter’s gun, the tinkle of cowbells, and the doleful nocturnal yelp of the coyote...

Some twenty years ago an old stage driver who still pilots a mud wagon through that locality on its tri-weekly trip to the Cosumnes, used to call the attention of his passengers to a little heap of stones, which he said was once a part of the foundation of a building that at one time was a Prairie City hotel. Now even that little pile of stones has toppled over, and the old stage driver’s trips have ceased. He too, has disappeared from the earth as completely as had the Prairie City of other days.430

In 1960, Plimpton, added an exclamation to the Union’s epitaph from 1906:

There is nothing left of the town of Prairie City, true, there is a house or two in the area, but they were built long after the town folded.” Prairie City “fell victim to the Gold Dredger shortly after the turn of the century and again in the 1930s, thus nothing is left to mark the sites except pile on pile and row on row of rock tailing, left by those dredgers after the earth was dug to a depth of some 40 feet and the gold lodged in it removed.431

As today’s traveler encounters the environs surrounding the vanished townsite near the highway interchange, a visage of natural resilience takes shape. The stark barren landscape of the early twentieth century, pockmarked with placers, is now obscured by oak woodland and grasslands. Endemic vernal pool complexes, though highly fragmented, remain in the area, some of which are protected at Prairie City OHV State Park.

The history of Prairie City provides a cautionary reminder. Modern Folsom development will soon extend south of the old cemetery and highway, its tentacles reaching into the obscured cobble of dredging and aqueducts of a goldfield and town once satiated only with the diversion of water. Memories of Prairie City fade at our peril.