Sins of Our Fathers

by A. R. Yngve

“I don’t believe in karma, father.”

“Is that so?”

“Don’t start again. Please.”

“It is your karma to marry, son. Can’t argue with that.”

There he goes again, Arrihant thought. Over and over, repeating the same old phrases. Why can’t he learn anything new to say? Arrihant tried not to look at his father Waman’s eyes, and instead gazed at the old man’s feet. Waman wore sandals; his toenails were thick and brown, scratched and bent with time and wear. Arrihant wore teflon-coated Nikes: self-cleaning, with built-in microclimate control; they never got clammy or hot.

Waman sweated in the humid, clouded monsoon weather; dark stains grew from the armpits of his tattered British wool jacket. Arrihant was cool in his ultra-thin t-shirt and boxer shorts, all “Made in Africa,” the home of cheap mass-produced goods. Animated commercials played on the t-shirt surface; images of products scrolled across Arrihant’s lean chest.

“Arri,” Waman said, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief, “you force my hand. If you won’t marry Rujula, I’ll disown you.”

Arrihant rolled his eyes, and scanned the cramped courtyard of Waman’s house. Some heritage to lose! Chickens went plucking and clucking around their feet. The walls hadn’t been painted in years. Broken solar panels adorned the corrugated tin roof. It wasn’t that Waman couldn’t afford new solar panels. The problem was that Waman didn’t want to call the repair service. He expected Arrihant to fix up the house every time he came for a visit. Arrihant had tried to explain that an expert should do the job and that he didn’t have time. Waman grumbled that his only son was lazy and selfish. So the solar panels had stayed broken since summer.

Arrihant’s mother appeared in the doorway with a tray of iced tea. She smiled at her son. “Will you stay over?” she asked, putting the tray down on the rickety table by the door. “I made your room ready, your old room. And I baked your favorite cake.”

She’s killing me with kindness, thought Arrihant, even as he smiled back at her. In his parents’ photo album were pictures of him from birth to adulthood. On each of those photos he was fat: cheeks bulging, belly spilling out, eyes piggy. How he hated those pictures. From the day he moved out, he struggled to lose weight and gave away the cakes his mother kept sending him. Now he was thin and in his prime, but in her eyes he would always be the Starving Child. “No thanks, mother. I’m not hungry. Really.”

“But you’re just skin and bones. If only your si...” Waman grabbed her shoulder and startled her. “That’s enough, Vatsa! You’re always spoiling him. You tell him. Tell him he shall marry Rujula.”

Arrihant took a deep breath; he was beginning to sweat, despite how hard his smart shoes and clothes worked to keep him cool. He looked helplessly into Vatsala’s eyes, pleading silently. Her adoring face wrinkled in an even wider smile. Killing him with kindness.

“Arri,” she said, and she clasped his arm, “Rujula may not be a beauty, but she’s nice... and her new set of teeth makes her look much, much younger!”

“No younger than forty,” Arrihant muttered. They did not seem to hear it. That middle-aged widow had borne four children before her husband died in the Sixty-Minute War, and hormone treatments just might enable her to squeeze out one more child... but Arrihant doubted it. Rujula was an old friend of the family and a genuinely nice person. It wasn’t her fault. It was his parents’. He wanted to pull away from his mother’s hold. Yet he stood there, letting her place a frosted glass in his free hand. The tea was a soggy mess. She had put too much sugar in it again. He raised his voice. “I’ll go abroad. I’ll find a girl. A blond one.” He said that mostly to upset them, and it worked. Again.

Vatsala flinched. “No, not one of those! They have no shame! They do things with other women, I saw it on TV! She would only leave you after a while, and then you’d be alone again. Find a nice Indian girl.”

“Or at the very least a low-caste girl,” Waman suggested, nodding to himself. “If there are no other options...” Suddenly Arrihant felt nauseous. He tore himself away from his mother’s clinging hands, spilling the sticky, oversugared tea on the ground. “I’ve had enough of this. And I won’t marry that woman! It’s my final word!”

His parents followed him into the street, pleading with him. A passing elderly neighbor waved at them and shouted — he was a bit deaf: “Good evening, Dr. Pankrat!”

Even as Arrihant sat on his bike and shut the plastic bubble around him, his parents kept talking to him. He ignored them and drove away. If he hurried through traffic, he could beat the next rainfall and be back for dinner. His phone beeped; he switched it off.

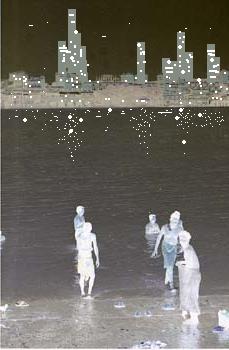

Arrihant swerved past trucks and automated taxis, through narrow, winding streets. Everywhere around him he spotted the same overall trend. On the city walls, sign after sign announced deals like: HOUSE FOR SALE — LOW PRICES! or: SEE DAUGHTER — ONLY 100K Rs! On the streets, only adults and old people — but no children. And of course, very, very few young women. He could glimpse the occasional little boy peeking out from inside a car, overfed and pig-eyed. But no little girls were to be seen. Nowhere.

Above, a passing zeppelin flashed news headlines and advertisements in five-meter letters: POLICE SMASH CHILD-STEALING RING — 20 ARRESTED... HEALTH ALERT: OVER-FIFTY FERTILITY DRUGS MAY CAUSE CANCER... DRINK BIN-LADEN COLA! IT’S A KILLER...

Poor old Rujula, he thought. She’d been taking lots of Over-Fifty drugs, or so she had told him. Society was putting an insane pressure on women like her to “give birth one last time.” Rujula could earn tax reliefs, state lottery tickets, even a used car if she had another child. She had confided to him, once his parents were out of hearing range: “I know I’m too old for you. We should be doing it for the good of society. The country needs more children.” And she had laughed in a manner that sounded a little bit insane. “I can’t believe I just said that... when I was young all they talked about was overpopulation.”

* * *

Arrihant shared his three-room apartment with a colleague from work, a flamboyant homosexual named David. (His all-Indian parents had named him after some celebrity who used to be well-known when David was born.) Much to Arrihant’s relief, David kept his own private life to himself, but he loved to chatter about Arrihant’s life. David could be overbearing at times, but on the upside he cooked great food.

When Arrihant entered the narrow hallway, he could smell pasta and garlic. David was into Italian these days. “About time, Arri! Now come to the table before the tomatoes are ruined. Jalla! Jalla!“

Arrihant hung his jacket on the chair, earning him a frown from David. “‘Jalla’? Since when are we Pakistani?”

David shrugged, and ladled steaming pasta and sauce onto Arrihant’s plate. “Nostalgia is in.” He was right: the kitchen radio was playing the hit song When Kashmir No Longer Glows At Night. “Now tell me everything. Did you or didn’t you?”

Sighing, Arrihant dug into his plateful of food. “Didn’t. My final word. I told him to his face.”

“And thank God! A bright young man like you, marrying that old cow? What were your parents thinking? Find yourself an African mail-order bride. That you can afford.”

“I’ll think about it. And what about you? Ever thought of having a family, just to get the money grants from the government? If love isn’t the issue...”

David acted insulted, but he didn’t really care. “Now don’t you start! I’d love to have children around the house, spoil them, see them grow up...” A vacant expression came into his eyes. “All my friends talk about it. Adoption. Finding a wife, a female one.”

“Do you have any women friends, Dave? Not drag-queens or transvestites. Real women.”

“They still exist, you know. But you’ve got to pay their parents through the nose to meet them. Prices are going insane! They’re not even allowed to have gay men for friends! How about that!”

“Insane,” Arrihant echoed glumly. “It’s bad in other countries... China’s very bad... India’s the worst. Our sex ratio was eighty-twenty on the last count. I hear the government is thinking of enforced birth quotas. At this rate, there’ll be less than three hundred million Indians left when our parents die off.”

“Why can’t the government pay for sex changes instead? Some of my friends would willingly have their willies cut off for Mother India.” He stopped giggling and looked at Arrihant. “Anything wrong with the food?”

Arrihant had stopped eating. “No. It’s just... I can’t talk to them anymore. They are infected by all this insanity. Of course I want to find a nice girl! Of course I want to form a family! If I could afford to meet a girl. If I could find one.” There was more, but he couldn’t express it in words. Something had been nagging him since his visit to the parents... “She tried to say something.” He stuck the fork into one tomato and rolled it around. “Dad interrupted her. She said... oh God. It can’t be true. ‘If only your sister...’ ”

“You have no sister...” David blinked. “Do you?”

Arrihant stood up and grabbed his jacket. He could make a simple phone call, but he knew that his father might interrupt again. He went downstairs and opened the garage. When he got into the bubble bike’s plastic shell, a heavy downpour started.

* * *

On the way back to his parents’ house, he turned on the bike’s Net-search program. “Request search for, quote: Close family of Arrihant Pankrat, 1990 to 2030, registered deaths, female subjects, names and age at time of death. Date of death. End quote. Start search.”

The weather was too heavy for the autopilot to handle traffic. Arrihant steered, wrestling the pressure of wind and water, and listened to the search program’s mechanical voice:

Searching... search found... 2 registered deaths, female subjects. One: Pholan Khandra. Age at time of death: 73 years. Date of death: December 23rd, 2026.

His father’s mother. The computer went on with his mother’s mother:

Two: Mira Shamalyan. Age at time of death: 58 years. Date of death: July 12th, 2013.

“Request search for, quote: Sister of Arrihant Pankrat. End quote. Start search.”

Searching... please wait... search found nothing. Continue?

“Quit search.” He parked the bike outside the old house and went into the courtyard without ringing the bell. His spare key opened the back door, and he quietly shut the door behind him. Listening and holding his breath, he could hear his father’s snoring from the bedroom. Arrihant entered the small living-room. There he picked out the family photo album from the bookshelf, brought it to the desk, and switched on the reading-lamp. The past had rarely interested him before; the future had always held more and better promises. It used to be his mother who showed him the faded photographs and newspaper clippings. He saw the photo of himself as a baby, held proudly by his father.

The picture of Waman standing in front of his then newly-opened, pathetically small fertility clinic: the sign above the door read DR. WAMAN PANKRAT, and next to him the sign with the promise: COME IN AND YOU WILL HAVE A SON! What a joke... “fertility“ clinic. Waman had made his career on cheaply and quickly selecting the gender of unborn children. Not always by legal means.

Other, paler photos showed dead relatives. All faces looked subtly different on the older photos: somehow more severe, as if having their picture taken had been a cause for mourning. So different from the confident, smiling faces of the newer photos. He noted another difference: among the photos of distant relatives, young females practically ceased to exist around the year 2020. (Waman had given all his relatives discount “treatments“ at the clinic.)

One cousin of Waman had had a daughter, shown as newborn on a photo dated 2022. But even though Arrihant had met his father’s cousin and her family, he had never seen their daughter. And she wasn’t dead, he knew that. She had been... locked up. Hidden away. A valuable source of income for her parents, no doubt, who could rent her out for chaperoned meetings with hopeful grooms, at grotesquely inflated prices. You’d pay the equivalent of a month’s wages just to sit and talk to the young lady, and offer her parents even more money to marry her. Greed. The name of the great insanity was greed.

He suddenly dared to think what had been smoldering in him for years: how deeply he despised his father, the “Doctor Death“ to countless unborn girls. Arrihant went through the rest of the photo album quickly, impatiently, but found no photo of a sister. He tossed the album to the floor, swearing. The spine of the book broke open, and he bent down to pick it up.

Something was sticking out of the album. He held the pages over the desk and shook them. A printed picture fell out; it must have been wedged in between two pages which were glued together. On the brittle, yellowed paper was printed an ultrasound image of a woman’s womb. The printout text was signed with the computer user’s signum: Dr. Waman Pankrat. The patient’s name: “Mrs. Pankrat.” The date of the image was September 13, 2001. He had been born on the 4th of January, 2002. There were two fetuses in the image of the womb. Two-egg twins. Each fetus had its own sac within the womb. One of them was male.

Arrihant’s hands began to shake. Waman and Vatsala woke up, hearing strange noises from the living-room. The rain was still hammering on the roof, so they could barely make out the new sounds. Waman, who had been robbed once, picked up his gun from under the bed and sneaked out. Vatsala waited by the bedroom door.

Waman found his son slumped over the desk, sobbing like a little boy. “Arri?” He lowered the gun and came closer to the circle of light in the darkened room. “What are you doing here in the middle of the night?”

Hiding his face, Arrihant peered down at his father’s feet — he had slippers on, with holes in front where the toes showed through — and held out the ultrasound image.

Waman gasped. “I told her to destroy that image. That stupid woman!”

“Was it you?” Arrihant blubbered. “Did you kill her? Was she ever born? Don’t tell me she died by herself! I know you better!”

Waman’s sloping shoulders rose and sank. “She never had a name.”

“Did... you... kill her?”

“Abortion is not murder. It is a standard medical procedure. I wrote the report. It says that your mother had a miscarriage.”

“As did all your other patients! All the deaths that just happened to be girls!” Arrihant faced his father, eyes swollen and red. “You dirty murderer!”

“I forbid you to talk like that! Haven’t we done everything for you?”

“Then why wouldn’t you give me a sister? Why didn’t any one of your patients want a girl?”

Waman shrugged. “You know... it’s just the way things are.”

“Karma, eh?” Arrihant bared his teeth in a terrible grin. “The karma that you made... the self-appointed god of men! Look at the world you made, father... a world where it costs money to just look at a young woman, where a whole country is shrinking away, a generation of men won’t ever find a wife because a generation of future women were murdered before they were born! By greedy bastards like you!”

Waman froze still, staring hatefully at his crying son. The gun was still in his hand.

Suddenly Arrihant lunged for the gun. There was a struggle. They knocked over the reading-lamp and the room went pitch-black. Vatsala came in at just the right moment to watch Arrihant empty the gun into Waman’s body. In every brief white flash of each bullet fired, she glimpsed Waman’s surprise, and Arrihant’s despair. The empty gun clattered to the floor. In the dark she heard the spattering rain, and the heavy sobs of a man. She thought she heard her son whisper: “I believe in it now, father...”

Copyright © 2004 by A. R. Yngve