Fevreblauby Kenneth Mark HooverONE |

Synopsis Biography Purchase link |

Two days before the Great Riot, it had rained in Moscow, and the streets surrounding Old Red Square glistened like waxed carbon beneath a dirty skin of rainwater. Fatly bundled pedestrians walked past the mag-lev terminal where he stood momentarily in the gloom, waiting.

Two days before the Great Riot, it had rained in Moscow, and the streets surrounding Old Red Square glistened like waxed carbon beneath a dirty skin of rainwater. Fatly bundled pedestrians walked past the mag-lev terminal where he stood momentarily in the gloom, waiting.

Eighteen months. Nikolai Sholokhov, electronics technician second class, belted the raincoat around himself. Eighteen months on Dark Side calibrating the Shklovskii radio-telescope array for the Star Whisper Project.

Now, he was home for two weeks. Then Dark Side for another year and a half, along with a guaranteed upgrade to technician first class to reward his troubleshooting skills on the Project.

A porter struggled to unload his luggage from an aluminum rack on the side of the mag-lev.

“Home for long, sir?” the grey-haired porter asked politely.

“I’m afraid not,” Nikolai replied. “Going back up in a couple of weeks.”

“That’s a shame, sir. Still, maybe it’s for the best.”

“Oh?”

“WeathCon says we’re in for a brief Indian summer the next week or so, before the first snows hit.”

Nikolai remembered the bitter Moscow winters of his boyhood. “Can’t say I’m sorry to miss that.”

The porter checked his baggage with a scrawled chalk mark. “How are you for accommodations, sir? There’s always spare rooms in the old Rossiya Hotel, and the price is right.”

“I thought it was gutted in the last riot.”

“The Rossiya? Oh, no, sir. She’s still standing like a proud lady. Clean rooms, and there’s smoked fish, even on the meatless days of the week.”

“Thanks, but I expect I’ll stay at the Warren.”

“I agree that’d be best for you, sir.” The old man smiled and Nikolai caught a glimpse of yellow-stained teeth. “Just thought I’d mention the Rossiya. You see, I get a couple of tsars for every client I send over nalevo.” On the side.

Nikolai nodded briefly. Obviously, things hadn’t changed since his last visit two years ago. Moscow was still on a barter economy and suffering hair-curling shortages. The Russian economy was stretched to the limit to keep her offworld colonies viable, especially after the devastation wrought by the gender sensitive plague that had decimated her female population.

The Porter handed him his bag. His thin arm seemed to bend under the weight. “Well, here you are, sir. Have a good stay. If you should need anything—tea, tobacco—I know a fellow. I’m always here at the station. Ask for Dmitri.”

Nikolai hefted his pood over one shoulder. “Thanks. I’ll remember.”

He began walking. St. Basil’s Cathedral, a gaudy mass of neon spires and gilded domes crowned with Russian Orthodox double-barred crosses, shone in the distance. Dying rays of sunlight gleamed off the golden cupolas. Further on, the red granite of Lenin’s Tomb—now a strip mall—and the pale brick of the Kremlin faded into velvet shadow as the sun rapidly sank beneath a bleak horizon. Traffic was light, but with many more military vehicles than he ever remembered.

Government banners flapped in a desultory fashion from the towers of the Kremlin. Giant placards of the First Minister’s taciturn visage hung from the shattered battlements.

Nikolai splashed through standing puddles of dark water. Near Sverdlov Square he passed a dead cat in the gutter. Stiff and soaked, it looked out over the wet thoroughfare with white marbled eyes.

He quickly adapted the standard Moscow shuffle: hands deep in pockets, head down. He took deliberate, measured steps, unaccustomed to the demanding pull of gravity. Movement out of the corner of his eye brought his head up.

Men darted across Gorkogo to queue up near a temporary market. Instinct moved Nikolai. He trotted heavily to the other side of the wide boulevard and joined them. There was general pushing and shoving as they settled down in their places in line. He counted the file of men ahead. He was twenty-third. Behind him, the queue already extended three times as far, with Muscovites still assembling. Nikolai waited, listening to the excited rumors fly regarding what was on sale.

A man ahead addressed his neighbor: “Fruit is what I heard. And about damn time, too.”

“They’ll probably run out of it when it’s my turn,” a wizened man behind Nikolai groused sourly. “Wait and see.”

“That fellow back there says they have cantaloupe. At twenty—”

“No, it’s peaches. Peaches and cream! Or syrup!”

“Don’t be foolish. When is the last time you saw a peach? It’s strawberries, I tell you. Strawberries and cream for thirty-six tsars. Can you believe it?”

“It’ll be gone by the time it’s my turn,” the old cobber growled again. “You watch and see.”

Nikolai removed his glasses and rubbed rain droplets from the plastic lenses with the fat end of his plain brown tie. He felt an odd sense of pleasure. This, and on his first day back on Earth! And in a few days he would have his Privilege. A queer, almost indefinable flush of well being settled over him.

The queue advanced rapidly. The aroma of sweets wreathed him. The street vendor, a stoop-shouldered man, subtracted thirty-six tsars from his credit disk and thanked him. Nikolai took a plastic spoon and left. Envious eyes watched.

He tore the cardboard lid off, ambling back across Gorkogo. Plump strawberries swam in cream that was remarkably fresh. He consumed it all. Before throwing the empty cup away in a compact recycling bin, he wiped his finger around the lip and sucked the remaining film of cream. He pocketed the plastic spoon.

There was a sudden disturbance behind him. A violent fight had broken out halfway down the queue. The argument spilled into the deserted street. There were shouts and curses as men tried to take advantage of the absent spaces and advance in line.

A pair of bluecaps ran towards the disturbance, brandishing shocksticks and blowing whistles.

Nikolai continued on to the Warren. Street lamps came on to cast harsh pools of blue light on the plascrete sidewalks. It began to rain again with nightfall.

“My name is Nikolai Sholokhov. I have a reservation.” He pushed his ident card through the aperture. The concierge accepted it and deftly slipped it in a slot on his security terminal.

“Another one from Dark Side.” It was a statement asking for confirmation.

“Yes.”

The concierge swung the flat computer screen away from Nikolai’s gaze as the information contained in his ID card scrolled on the security console.

“I’m from Kiev II, Korolev Crater, sector five block nine. I’m here on rotational leave. You see, it’s my Privilege, so I made reservations two months . . . .” he stopped. The concierge didn’t care, and besides that . . . Nikolai’s legs hurt terribly. The brief span of days spent aboard Mir VII’s one gee gymnasium in cislunar space hadn’t adequately prepared him for the sudden burden of weight he now felt.

“Yes, yes. I understand.” The concierge handed back the card and opened a barred-glass door. “Go to the front desk and ask for your room number. Give them this.” The man held out a blue Warren-ident card with a holographic imprimatur and gold border.

Taking the card, Nikolai muttered “Thanks,” and went on through. The glass security door hissed shut behind him, clicked.

A second man behind the lobby desk, bored and sleepy, checked him in and subtracted one thousand five hundred tsars from his credit disk for the night. He handed Nikolai a cheap, palm-lock key stenciled with a room number.

“Sixteenth floor. Pay for another day everyday at noon.”

Nikolai nodded that he understood and entered one of the four lifts servicing the twenty-story building. Inside the car he leaned against the tarnished brass rail, feeling tired and alone. He ignored the security ‘scope that watched him from the top corner of the car.

The elevator inexplicably stopped on the fourteenth floor. Its doors trundled open to reveal a plastic sign on a wobbly stand in the hall.

Lifts Inoperative Above 14th

Use Service Stairs

He groaned. Climb stairs, with his throbbing feet and legs? Murder. He shuffled down the brightly lit hallway and mounted the plascrete stairs. Halfway up the stairwell he had to pause and rest, and was huffing by the time he gained the sixteenth floor.

When he reached the stairwell door, it banged open and three small boys raced past. One bumped into him, causing him to stumble. The tow-headed boy didn’t stop to apologize or help, he just flew after his companions, hooting and yelling. Their dwindling shouts echoed up through the stairwell.

Nikolai found his room, 1644, blessedly near the stairs. He unlocked the door, reached for the light pad.

His quarters were one room with bath and a bed. He turned up the corners of a mattress that smelled of camphor. No bedbugs. In the kitchenette, a small portable refrigerator was bolted to the marred Formica counter, along with a two-range electric stove. The cabinets were bare. A dirty, worn rag lay in the sink. He surveyed the remainder of the barren room. Cheap Goya prints hung on the vanilla walls to hide the worst cracks and water stains. The yellowed lacquer on the wainscoting was chipped and peeled with neglect.

He shrugged at the surroundings. He had lived in worse.

He unslung the travel bag from his shoulder and gratefully collapsed on the edge of the soft bed. He kicked off his damp, rubber-soled canvas shoes. Massaging his burning calves with one hand, he keyed the vidphone by the bed and asked for Union House. Waiting for the call to complete, he switched on the computer terminal and punched in a string command for a local news/radio station. Mozart swelled from the speakers. He turned down the volume when a voice promptly answered his call.

“Union House. Can I help you?” A man in a neatly pressed uniform appeared on the flatscreen. Nikolai cued his own screen and consulted his official cablegram.

“My name is Nikolai Sholokhov. I have Privilege scheduled Thursday night, and I want to confirm.”

“ID number.”

He gave it to the operator, along with his work and social numbers. A brief pause ensued while the operator consulted his terminal.

“We have you down for 2230, Thursday.”

“Yes. Yes, that’s right.” His pulse quickened as the confirmation came through. “Okay?”

“Fine. Bring the necessary identification cards and your State release, and final receipt of social duties paid. Be here a few minutes before your appointment so we can prepare you.”

“Yes. I’ll be there.” The operator broke the connection.

Nikolai turned up the radio volume and lay back on the thin mattress. He removed his glasses, turned out the lights of the room from a master switch on the computer console, and threw a forearm over his hot, tired eyes.

He tried to think of whom else he could call while he was in Moscow, but no one came to mind. Most of the boys he knew growing up had moved on, or were working in one of the orbital factories. More than a few had been killed during the Encroachment War with Mongolia. Like most Muscovites, he had never forged close relationships. There was no emotional profit in it. People moved on when they could, forgot their past when it was convenient. Russia was a raped and barren country. Nothing like the vibrant nation of natural resources it was reputed to have been during the Mad Times.

He worked at a strawberry seed between his teeth with his tongue, half listening to the newscaster drone on and on about a large chemical spill off the Japanese coast, near Sakhalin. And the West had failed to reestablish contact with their experimental beam-rider spacecraft to Proxima Centauri, and heads were going to roll: Literally.

Another red tide bloom in the Gulf of Mexico: no surprise there. Word out of China was they had successfully integrated the thought-shards of an independent AI, but it had somehow got past its Turing horizon and was now running loose in the DataSphere. Scary stuff, if true. Scattered fighting around the world. Riots in Madrid. London was still burning; the dikes had failed and New York was flooding—again.

He fell deeply asleep while the radio played on:

“You are listening to Radio Moscow, the voice of the Confederation. The time is ten o’clock.”

“Nikolai. Wake up, Nikolai. Nikolai, wake up.”

He rolled over and keyed the appropriate button. “I’m awake.” He rubbed sleep from his eyes. “What time is it?”

A dulcet voice said: “Twenty minutes past noon.”

He grunted and kicked the harsh sheet from his naked body. He had stripped and set the alarm during the night. He twisted around and looked at the terminal.

“What name do you use?” He yawned and rubbed his sore calves.

“I respond to Sonya,” the AI said. “I am a Metchnikoph VI model, room maid class, installed on May 7, 2125. I am directly plugged into State Central and the DataSphere. I will handle daily expenditures, remind you of any appointments and screen all your incoming calls. My Turing rating is—”

“That’s fine. You needn’t go on.”

“I am here to serve.”

He rolled out of bed while Sonya ordered his breakfast. Grabbing a clean pair of underwear, he hobbled to the bathroom where he showered and then shaved his three days growth of beard. The mirror over the scalloped sink had lost most of its silver backing. His drawn, twenty-one year old face with its wide-spaced grey eyes and thinning straight hair looked like a ghost. He washed the sink with a thin washrag, scrubbing at a ring of green-brown slime around the drain. He pulled on a worn pair of blue coveralls with a black nylon belt and canvas shoes that had dried over the tiny radiator by his bed. A knock at the door interrupted him. It was room service with his breakfast: powdered eggs, two small strips of real bacon, watered-down juice and two stale but thick slices of homemade black bread. The meal cost twenty-five tsars.

He pitched the paper plates in the incinerator chute behind the kitchen sink, but kept the plastic cup, rinsing it out for future use. He fished out his ID and credit chips from yesterday’s pants, counting out his remaining money: five cards of ten thousand tsars apiece, minus what he had spent for the room plus strawberries and breakfast. He was doing okay. Warrens were set up strictly for the use of Confederation offworlders like him, and granted extra credit if one happened to run short.

He picked up his raincoat and shook it out. “I’m going out, Sonya,” he said, preoccupied with hand-pressing some of the larger wrinkles. “I should be back around 2000 hours or so.”

“Nikolai,” she warned, “I suggest you not overtax yourself. You are not acclimated to the gravity yet.”

New arrivals from Luna tended to overextend themselves the first day back on Earth. It was her duty to remind him of this.

“I’ll be careful.” He shrugged on his coat and left.

He went shopping, purchasing toiletries from the myriad stalls open to the fresh, clear air in the bright August sun. Other people were about, taking advantage of the good weather, or riding the electric trains to the wooded outskirts of the city to pick wild mushrooms.

He shouldered his way through the crowds without looking at anyone.

Late in the afternoon, he paid one hundred and fifty tsars to see a pornographic film featuring virtual actors. He had cautiously chosen one of the better-looking theaters, staying away from places that had too many boys hanging around.

It was warm inside the theater, and he had to remove his coat. The air stank of stale cologne. The soiled seat would not fold back, but it was comfortable and the armrests weren’t begrimed. A ubiquitous trash of wrappers, cigarette butts, and punctured tubes of euphoria dollops littered the porous floor.

When the lights went up, an usher shuffled down the aisles to make sure no one tried to stay for a second showing without paying. Nikolai grabbed his coat and left.

Outside he blinked rapidly, eyes tearing at the swollen afternoon sun just touching the jagged rooftops. He took off his glasses and wiped his eyes.

He casually headed back to the Warren by way of a corner grocer’s, but on impulse turned into a pop shop. He browsed unhurriedly, one of a score of men jammed in the stifling place. There were the usual magazines, videos, and interactive software. Another wall carried wallet-sized cards and 3V posters. He examined one of the manikins. He had never been able to bring himself to use one, although those who knew maintained one couldn’t tell the difference. Nikolai doubted that—and his mind veered to Thursday night. He went out to the cool evening air. This pop shop didn’t offer anything the stores in Kiev II didn’t have. Anyway, he would have to pay a steep duty on anything he brought back to Luna.

He pushed toward home, purchasing a few days’ worth of groceries from various stalls, and a daily newspaper loop.

It was evening when he reached the Warren. Its steel and glass facade sparkled under the soft yellow bioluminescent street globes that illuminated the grounds. Almost as if twilight beckoned them, the boys were out roaming the streets. Many stood on the corners; some walked and worked the immediate vicinity of the Warren, looking for an outworld customer who might be interested in a new face, a new body. Most of them were tall gangling youths with long hair and diversified styles of dress. Their arms and torsos sported smooth, firm muscles. There were couples going out in the night to a restaurant or symphony. All were of mixed ages, all were men.

In Moscow, as in most of Russia and the entire world, the only women present were those of the giant Union Houses, and one had to have paid social duties to receive the privilege of accompanying one, if only for an hour. It had started with gender selection—modified centrifuges with separating electrical fields, glass tubes of filtering serum albumin, X and Y chromosomes. Female infanticide in population pressure spots: India, Central Africa, Asia, Hot West ‘Merica. Men traditionally valued more than women. Then the gender sensitive virus with a shifting antigen hit like a firestorm: The Fevreblau. Some said it originated in the West, with the CDC in Atlanta, or from God, but who really knew? Trillions were spent worldwide to find a vaccine, bankrupting nations. A nightmarish sociological disaster no one had ever expected or imagined, had come to pass.

It was an apocalypse not foretold by any prophet of any belief system in any age of the world.

Women who survived the Blue Fever (roughly one in every five thousand) through some lucky genetic roll of the dice found themselves protected and sheltered. They supplied crèches with their ovaries that birthed male children to staff depleted armies, sustain the work forces, racing to keep a sliver of humanity from the precipice of extinction. Women were Exotics, used to prevent populations from dissolving in a shattered world. A history gone mad.

That night, Nikolai lay in bed, lights off, listening to Ohta’s 9th symphony. The music washed over him. He thought of the boyhood friends he had once known. Names forgotten and lost. A life unremembered. When the music ended, he switched the radio off and tried to rest, forcing himself not to masturbate. He kept thinking of Thursday, and wondered what she would be like.

Choking back a cry, he bolted up in bed. He crouched over, propped on both arms, head down. His hair was stringy with sweat.

“Nikolai?” Sonya. A red light near her fish-eye lens intensified. She studied his configuration with her infrared screen. “Are you ill?”

He leaned on the headboard, slicking it with sweat.

“Bad . . . dream.” He coughed. “Nothing else.” His heart rate slowed. He looked at the disk of light on Sonya’s console, tried to make a joke of it: “Nervous about my appointment on Thursday, I guess.”

“That is a common reaction,” she assured him in a maternal tone. “Most males experience it in countries with an unstable population ratio. Do not be alarmed.”

He crawled out of bed and drank a cup of water. When he returned, Sonya asked, “Have you recovered?”

“Yes, sufficiently.” Back in bed, he stared at the darkened room. His skin slowly dried.

“My psych program recognizes this as a classic anxiety pattern. Go back to sleep. Please, rest.”

But the apprehension of what lay ahead at the Union House was too much for him. He got out of bed again and started dressing. The tattoo watch in the palm of his hand read 0415 hours.

Early, but he hoped a bit of food and the bright lights of the commissary were what he needed to chase away the last shreds of his anxiety attack.

He told Sonya where he was going, and locked the door to his room with the palm-lock. He trudged down the flights of stairs to a floor where the lifts were working. A few minutes later, he entered a well-lit cafeteria. The place was empty, except for one man sitting with his back against the wall and huddled over a cup of coffee as if trying to draw warmth from it. He used a blunt forefinger to push chess pieces around on a board painted onto the table.

Nikolai coolly inspected the stranger. Pale blue eyes. Blond hair with tight curls. Heavy jaw, and bushy eyebrows that crawled like wooly caterpillars across a domed forehead. An expensive coat with sable trim was folded carefully on the bench beside him.

Nikolai drew his own cup of the thick brown liquid from a samovar and was about to sit down at another table when the man spoke.

“Hello. Didn’t see you come in. Thought I had the place to myself. Can’t sleep either, eh?”

“Not really.”

“You look like you could use some company. I certainly could. Mind if I join you?” He started to get up, Nikolai waved him back down and slid onto a bench opposite the table.

“Name’s Yuri Tur.” The stranger held out a big paw. His handshake was dry and firm, his fingers thick with yellow calluses.

“Nikolai Sholokhov.”

A look of surprise. “Say, you’re not from Dark Side, are you? Working in Sharonov Crater?”

Nikolai suddenly became leery. The Star Whisper Project was an ultra-secret program. He knew everybody connected directly to the project, but this man was a complete stranger.

Still, he thought, if there’s been a security leak I’d better find out who this cobber is and report him to the bluecaps.

He drew a poker-face. “Why do you want to know?”

Yuri inaugurated his next words with an easy-going laugh designed to put anyone at ease.

“Because, Sholokhov,” he chuckled softly, “I’ve been contracted to kill you.”

(End of chapter one)

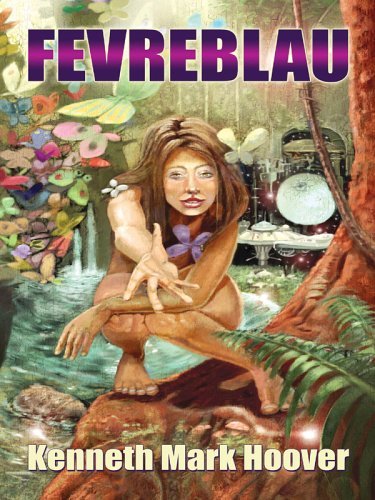

Fevreblau explores a future from the viewpoint of ordinary people trapped in extraordinary circumstances. The novel is fast-paced and exclusively set in “exotic locales” of Moscow, and an orbital habitat in cislunar space.

The story opens with Nikolai Sholokhov arriving in Moscow for what is euphemistically called ‘Privilege’, after spending eighteen months on the Moon calibrating an array for the Star Whisper Project —an ultra-secret program that has detected radio signals around a distant star in the constellation Hercules.

However, the only women in Moscow are those in the Union Houses. Earth was decimated by a gender-sensitive virus that raged across the globe a century ago: Fevreblau. Women who survived the Blue Fever now find themselves sheltered by the State. They are considered Exotics, used to prevent populations from dissolving in a shattered world.

Before his scheduled appointment, Nikolai meets an adroit thief, Yuri Tur, who in turn introduces him to Moscow’s premier underground leader, Mintz. Mintz is interested in the alien signals detected by the radio-telescope.

Nikolai also befriends a frightened young woman, Galina Toumanova, fleeing one of the larger Union Houses during a city-wide riot. Together, they make a daring escape south to Star City (Baikonur Cosmodrome) and into the Archipelago — orbiting habitats in cislunar space.

Once there, Nikolai discovers he is at the epicenter of a sweeping revolution that will change the basic social dynamics of Humanity, and the culture of an entire world.

Kenneth Mark Hoover has sold over thirty short stories and articles to professional and semi-professional magazines. His first novel, Fevreblau, was published by Five Star Press last year. This is his second appearance in Bewildering Stories.

Mr. Hoover currently lives in Mississippi with his wife and children. You are invited to visit his web site and his online journal, Inky Horizons: Celestial Musings of a Science Fiction Writer.

The link to purchase Fevreblau is at Five Star Science Fiction.

Copyright © 2006 by Kenneth Mark Hoover