The Rediscovery of Menander

“An Ongoing Modern Miracle”

by Bertil Falk

How much do we owe the past? If Virginia Woolf is to be believed, a lot. Referring to “those forerunners,” she stated that without them “Jane Austen and the Brontës and George Eliot could no more have written than Shakespeare could have written without Marlowe, or Marlowe without Chaucer, or Chaucer without those forgotten poets who paved the ways and tamed the natural savagery of the tongue.”

How much do we owe the past? If Virginia Woolf is to be believed, a lot. Referring to “those forerunners,” she stated that without them “Jane Austen and the Brontës and George Eliot could no more have written than Shakespeare could have written without Marlowe, or Marlowe without Chaucer, or Chaucer without those forgotten poets who paved the ways and tamed the natural savagery of the tongue.”

And (a dangerous thought), I may add, would Ray Bradbury have been able to write The Martian Chronicles the way he did, had Stanley G. Weinbaum not written A Martian Odyssey in 1934? And would Seinfeld and Friends have been what they were (and still are), had not Menandros graced the soil of Greece in a distant past?

In the year of 2003 a fragment of a comedy by Menandros (also called Menander) was found in the Vatican. Menandros lived 341 - 291 BC. Up to 1907, his work was known only through copycats and preserved familiar quotations. But in the 20th century he made his comeback. Discoveries of manuscripts in the desert sands of Egypt, findings of fragments in libraries and laborious handling and decipherment of papyri that had been used to make papier-mâché for mummy cases have given his art a new lease on life. Isn’t that like science fiction coming true?

The rumor had gone in advance of him. The sententious phrase “Oh Menandros, oh life, which of you copied from the other?” was coined in Rome. Menandros was also “co-author” of the New Testament. For when Paul in The First Epistle to the Corinthians, 15:33, exclaims: “Bad company corrupts good morals,” he is citing Menandros. And who has not heard the expression: “Those whom the gods love die young”?

It was the fate of Menandros that his literary remains for a long time consisted of isolated remarks and platitudes. They made posterity of two minds about him. As if in the future one might have to judge Ingmar Bergman from fragments of Torment (writer, 1944) and All These Women (director, co-writer, 1964).

There was of course the plagiarism of the Roman comedy writers. Plautus (254-184 BC) adapted works by Menandros. The emancipated slave Terentius (195-159 BC) plagiarized Menandros. Julius Caesar, who liked Terentius, nevertheless described him as a half Menandros.

About fifteen comedies by Menandros are said to have existed in Constantinople in the 16th century, but if that was so, they have now disappeared. It was to a great extent thanks to Plautus and Terentius that the traditions from Menandros were kept going. And they are clearly visible in the works of such as Molière in France, Shakespeare in Britain, Holberg in Denmark, Alexander Johann Stender in Latvia and Olof von Dalin in Sweden.

The rediscovery of Menandros began when archaeologists found a papyrus in Egypt in 1907. The lawyer Dioskoros had owned it. He lived in the middle of the 6th century. The tattered document was put together, three comedies were reconstructed, chiefly two-thirds of Epitrepontes (The Arbitration; Desperately Seeking Justice), which became stageable.

More fragments were discovered. When a complete copy of Dyskolos (The Grouch; The Bad-Tempered Man; Old Cantankerous; The Misanthrope) came up to the surface in 1957 in the form of 21 papyri, it was quickly translated into Swedish and Danish. On May 3, 1959 Dyskolos had its second world premiere, as a radio play on both Radio Denmark and Radio Sweden.

The commonplaces were explained. Menandros described his characters by letting them talk rubbish. So even if this is a quotation from Menandros — “of all wild beasts on land and at sea, the woman is the most wild” — it does not necessarily reflect his opinion. The words are put into the mouth of one of his characters.

When Dyskolos was found, the Swedish ambassador to France, Ragnar Kumlin, waxed lyrical and exclaimed: “There is, if anything, an evidence of the popularity of Menandros during the antiquity that almost every excavation produces fragments of his comedies.”

Aristophanes is always topical. He represents the older Attic comedy when Athens was a great power. Sweeping and grandiose devices, making fun of contemporary celebrities, current political commentaries, imaginative plots, war-weary, peace-mongering and love-striking women. Aristophanes was the practician of the broad outlines in his parodic, variety-like comedies.

But when the new Attic comedy flourished with Menandros, one hundred years later, Athens had been downgraded to a part of the Macedonian nation. Now that Athens was turned into a remote and powerless appendix of the empire of Alexander the Great, the comic playwrights of the new Attic comedy limited their activities to the problems of everyday life. Instead of high-flown language, colloquial speech, instead of gods and heroes, ordinary persons, crafty slaves, cooks and hetaeras with hearts of gold.

To make the time-bound allusions of Aristophanes intelligible to a modern audience, his comedies are today often revised to the equivalents of our time.

Menandros need not be adapted like that. He talks straight to us over a gap of 2,300 years. His sense of humor is timeless and universal, not contemporary satire. Even so, his comedies are rarely performed.

From the tragedian Euripides, Menandros borrowed the plot with mistaken identities. The small book The Characters by the zoologist and botanist Theophrastus is supposed to have been a condition for the cast of Menandros’ comedies. Theophrastus systematized thirty different characters, such as: the flatterer, the superstitious man, the talker, the authoritarian, the slanderer, etc. All these conceptions are reflected in comedy titles like The Grouch and The Ass-kisser by Menandros or The Miser, The Misanthrope and The Imposter by Molière or Bêrtulis, The Drunkard by Alaxander Johann Stender.

This 2300-year old tradition arose when Menandros set different characters against each other. For example, in Dyskolos, the gruff farmer Knemos, father of a beautiful daughter, shows his misanthropic character especially to young, lovesick snobs from Athens, who come courting his daughter. This is how Knemos sounds in the translation of Carroll Moulton:

Old Perseus was divinely favored — twice!

He had his wings and didn’t have to meet

a single passerby. He also had

that thing to change the men who bothered him

to stone. What fine possession! I

wish I had it now — I’d convert

this place into a sculpture garden!

Life is unendurable, by heaven,

when chattering strangers trespass on your land!

You’d think, by God, I liked to waste my time

along the highway! Well, I’ve given up working

on this section of the farm. Too many people

Bother me. Just now they’ve chased right up the hill

to get at me! God damn these wretched mobs!

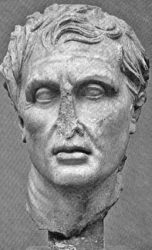

We do not know much about Menandros. He was interested in women, but who has not been interested in women? He lived together with Glykera. But there are many heads representing Menandros from the antiquity. When the brain surgeon Temple Fay saw a Menandros head in the 1920’s, he noticed certain symptoms in the facial symmetry that some of his neurological patients also showed.

When he returned forty years later and measured the head, he found that the right side of the face was substantially underdeveloped, something that also can be seen on other heads of Menandros. They seem to be cock-eyed. Temple Fay interpreted this as spastic paralysis. His diagnosis was that Menandros had been stricken with cerebral haemorrhage before he was ten years old.

Menandros is said to have walked in a strange way and have been squint-eyed, but there is no information about him having epileptic fits like Temple Fay’s patients. He drowned some time around 291 BC at Piraeus. Suicide? Accident as a result of an epileptic fit? Or simply a cramp when bathing?

One of the translators of Menandros, Sheila D’Atri, has aptly described the recovery of the almost complete text of the Dyskolos “as an ongoing modern miracle.” Let us hope that the deserts of Egypt, old mummy cases and other sources during the 21st century will continue to plug the holes.

To be sure, Seinfeld and Friends, as well as other sitcoms, are descendants of Dyskolos.

And finally, a word of wisdom from Dyskolos, in the translation of Norma Miller. It almost sounds like a quotation from Havamal:

A real friend is much better value

Than secret wealth, kept buried somewhere.

Further reading:

Theophrastus, The Characters & Menander: Plays and fragments (Translated by Philp Vellacott, Penguin, 1970)

Menander, The Dyskolos (Translated with an introduction and notes by Carroll Moulton, New American Library, 1984)

Menander: Plays and fragments (Translated with an introduction by Norma Miller, Penguin, 1987)

- Menander, introduction by Sheila D’Atri

The Grouch (Translated by Sheila D’Atri)

Desperately Seeking Justice (Translated by Sheila’ D’Atri and Palmer Bovie)

Closely Cropped Locks (Translated by Sheila D’Atri and Palmer Bovie)

The Girl from Samos (Translated by Richard Elman)

The Shield (Translated by Sheila D’Atri and Palmer Bovie) (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998)

Copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk