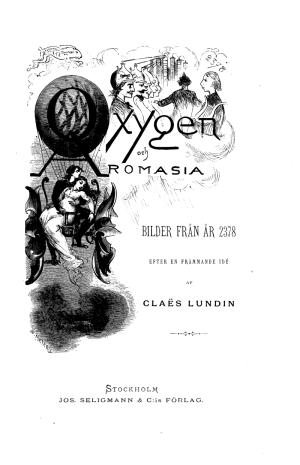

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 2 appeared in issue 257. |

| Chapter 3: A Tempest Man |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

An air taxi stopped outside the window. Oxygen was arriving at last. Aromasia dashed at him and greeted him heartily. Even the poet shook Oxygen’s hand.

Oxygen Warm-Blasius was a young man, perhaps a little older than the poet. He had profitable profession that was held in high esteem: he owned a factory that manufactured weather. Thus he might even be called a tempest man as well as a sunshine being.

Oxygen oversaw a big workshop that produced very high-demand machines for causing changes in air circulation. The process used chemical and physical forces that disengaged gas; warmed and cooled huge air masses; sucked the upper strata of air downwards and pushed the lower strata upwards; formed or dispersed clouds, everything according to the need of the moment.

Oxygen had a high reputation and considerable income, for his share of the company generated an annual profit of some hundred thousand francs. Nevertheless, this company was almost what they used to call a “production association” in the 19th century.

After saying hello to Aromasia and her guest, he rushed to a microscope placed on a table by the window. “Excellent!” he exclaimed. “I congratulate you, my dear Aromasia. I’ve seldom seen such excellent primordial slime as this. You’ve been exceedingly successful.”

“Yes, it’s not bad,” Aromasia admitted. She too bent over the microscope and looked quite attractive as she added, “How many times I’ve sat here and observed the cell formation.”

In the 24th century, it was a customary social amusement and a pastime of odd moments to extract the so-called primordial slime — the lowest organic formation — from inorganic matter. Professor Ärencell had had the victorious pleasure of observing the first unquestionable occurrence of spontaneous generation. Instead of playing with parrots and lapdogs, the ladied nowadays were occupied with watching cute primordial slime under the microscope.

“You’re late as usual,” Aromasia continued, “but I guess you have a lot to do.”

“Yes, the factory is overburdened with orders,” Oxygen answered. “The weather has been unusually dry for some time, and we’ve no end of trouble to obtain as much rain as our customers need. But we must not come up with one single drop more than is considered necessary for the time being. I hardly think that any profession has customers as hard to please as we have.

“One air message after the other accumulates over us: ‘Why are you not willing to execute our orders?’ they say. We ordered rain a couple of days ago and we’ve still not received one single little splash’.

“Well, then we execute the order, but in our hurry we’ll perhaps pump in a little too much. ‘Are you people crazy?’, they say, ‘Are you going to drown us? Get us sunshine immediately, and make it quick’.

“‘Rain!’ They scream from one quarter. ‘Sunshine’, from another. And everything has to be arranged immediately. However, right now mostly rain is in demand. We’ve been forced to raise the price of raindrops because of the heavy use of raw materials and the increased need for manpower.”

“But isn’t temporary assistance enough?” the poet objected.

“You always live in days long gone,” Oxygen replied. “It was the misfortune of the working conditions of ancient times that temporary labor was necessary. People were paid a daily wage or, at best, a fixed annual salary; or they did piecework. But that wasn’t really practical. Day laborers were lazy, of course. Why should they work hard, since they would not be paid any better? Why should the salary-earner work himself to death? No, as little work as possible, was their attitude. And those who worked by the piece were careless, of course, in order to get their pay faster. It’s only profit-sharing that can create good, careful, skillful workers.”

“But if there’s no profit?” was another objection.

“We have various profit-insurance companies, which compensate us until better conditions occur. Why should we pay them their annual premiums otherwise?”

“Oxygen is absolutely right,” Aromasia put in, “and there is no doubt about that any more. Only such an eager supporter of everything antiquated, like our friend the poet, can speak of wages and temporary labor. That was already settled four hundred years ago, and if the horrible socialist wars of the 20th century didn’t do anything else, they at least put an end to many old prejudices in economics.

“But now I want to bring up another topic. As you know, I have a concert tonight, one hour after the end of the main meal of the day, but could we three not dine together? Will you permit me to be your hostess? I invite you to the Central Hotel. You’ll come, both of you?”

The tempest man and the idealist accepted and promised to turn up at the appointed time, whereupon Aromasia declared she would prefer to be alone in order to prepare herself for the evening concert.

Before the two men bade farewell, Oxygen said, “I, too, have a suggestion, but it’s about tomorrow. I’ve now arranged so much rain for our customers, that I believe that I can use my day off...”

“Do you all have such free days?” the poet interposed.

“Of course we have,” Oxygen replied showing some surprise. “Don’t you know that? Every worker — and this concerns all professions — every manager or performer, is free every tenth day. That’s the law, and nobody can be denied utilizing that free day. But every person is permitted to work on the free day, of course. Tomorrow is my free day and I’m not going to work. I know that Aromasia as a free artist can take a day off whenever she wants...

“But is this right?” the poet inquired.

“Right or not, that’s the way it is,” the weather-manufacturer replied, “and we won’t discuss the social question now. You, too, my friend, can probably use a free day whenever you like, which to be sure not is right either, but it would be convenient tomorrow, if you want to join in an excursion with us.”

“An excursion!” Aromasia exclaimed. “Where?”

“I thought of North America. We’ll still have dry weather for some days in the Northern Hemisphere, and it would be just right to pay a visit to Niagara!”

“Oh yes!” Aromasia exclaimed. “To see the place where the remarkable waterfall once roared. But should we not include Aunt Vera?”

“I would like that,” Oxygen explained, “but I fear that the old lady isn’t capable of going on such a rather long journey.”

“You may be right,” Aromasia admitted, “but it is a pity. Aunt Vera is a very kind old dame.”

“It’s said that in former days old women like her went on even longer journeys in the air, on a broomstick,” the poet joked.

“That’s a bad joke,” Aromasia said. “It dates from the days when there was no respect for women, least of all for the older ones of our sex.”

“Now the elderly woman is venerated,” Oxygen put in, “as much as the elderly man is. And in a similar way not even the youth is held back any more. That’s the habit of our time.”

“And furthermore,” Aromasia added, “Aunt Vera has accomplished very much in her younger days. She was an active partner and co-owner of her husband’s wholesale business, and after his death she was in charge of the office for many years. There was not one day that she was away from her desk and no evening that she didn’t gather the younger partners of both sexes for lectures, discussions, games, and sometimes dancing and other amusements. Everyone was a member of the family. Nobody had to find entertainment outside, although they did sometimes go out, especially for plays, concerts and public lectures.

“I’ll grant the good lady my absolute respect,” the poet declared, “but she would not have been fit for a sonnet a couple of centuries ago.”

They said goodbye and promised to met at the Central Hotel.

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk