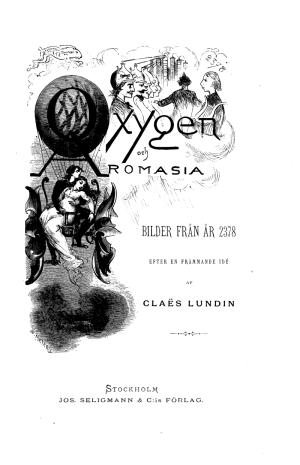

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 7 appeared in issue 261. |

|

Chapter 8: A Parliamentary Election and Pangs of Love |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

”Why do you want to be elected?” Oxygen was asked by one of his friends.

”Why do you want to be elected?” Oxygen was asked by one of his friends.

In the 24th century, the honorific Swedish form of address ni (actually a plural form meaning ‘you’) had not yet gained currency. But it was much more common than it had been in past centuries. The old habit of “drop the titles and drink on it” had not entirely disappeared, but it had become less common because of more frequent contacts with European and, especially, Asian people.

The form of address du (the singular form for ‘you’) was used within the family or among those who began the year of probation that always preceded marriage. This word was never used when addressing someone you did not want to reply in the same way.

A collaborator, or what was called a servant in the past, was never addressed using second person singular du but always with the second person plural ni. This new form of address was considered a social improvement.

Oxygen's friend was not close enough to address him with du, but knew him well and was sufficiently interested in his actions to ask the weather manufacturer about his reason for seeking the candidacy for the parliament.

Oxygen looked embarrassed. He talked about his wish to accomplish something with legislation and his desire to be of use to society and so on.

The friend shook his head and did not seem convinced of Oxygen's explanation. “That's an old-fashioned mode of expression and isn't valid nowadays. You don't happen to be ambitious? Is your occupation not enough? Isn't it satisfying to make rain and lovely weather?”

Oxygen remained silent.

“Have you forgotten,” the friend continued, “that if you're not nominated by at least fifty people entitled to vote and yet you seek election, then you have to give a public explanation?”

No, Oxygen had not forgotten. And he declared that he was not ignorant of the fact that the public explanation would be subject to a rigid examination. But he did not want to continue the conversation. He said a hurried goodbye to his friend and rushed away.

“For some reason, the honest Oxygen seems to be dissatisfied with the beautiful Aromasia and wants to keep her out of parliament,” the friend told one of his acquaintances.

“The election in Majorna is one of the most important in Scandinavia,” another person remarked.

“And it may have an influence on all of northern Europe,” a third added. “We should watch it carefully.”

The same happened everywhere. All of Gothenburg, especially Majorna, was abuzz. Men and women hardly discussed anything else. Every day, public election meetings were held. The talk-mechanic was incessantly at work.

To begin with, most people had spoken favorably of Aromasia, the great artist, but after a couple of days, those, who had declared themselves to be firmly in favor of her, showed some hesitation. A resistance had emerged, it was not known how, but it was doing its best to manifest itself.

To be sure, the rumor that Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar sought the seat turned out to be unfounded, but the hale and hearty lady passionately worked for the election of Oxygen. Miss Rosebud was even more energetic, though she did not appear in public and supported Mrs. Sharpman behind the scenes.

Of Majorna's newspapers, The Proud Air-Bubble had suddenly changed its opinion and opposed Aromasia as vehemently as it had endorsed her election previously. The Farthest Outpost, a respected paper in the suburb Marstrand, claimed impartiality since it did not cover the same district as The Bubble, but its attacks on the candidacy of the artist were equally violent. Most of the other seven hundred and fifty-five newspapers in Gothenburg still endorsed her, but not at all with he same alacrity as a few days earlier. Those who had encouraged Aromasia to run for office began to be discouraged.

One who never yielded his zeal was Apollonides. As a poet-engineer at parliament, he was not without influence.

He traveled from the one meeting to another, shared his time between Gothenburg and Stockholm, talked to as many voters as possible, forced his way into newspaper offices, tried indefatigably to press his conviction as well as his words for The Seasons.

He was distressed that in all this time she did not want to receive him. That did not diminish his eagerness. “Eventually, she will hve to yie.d to such unselfish devotion,” he said to one of his friends.

“But Aromasia doesn't love you,” the friend remarked.

“She will,” the poet assured. “She can't go on loving a man who with raw selfishness wants to force himself into parliament at her expense?”

“Oh, you're still trapped in the old way of looking at things.”

“On the contrary! I'm a modern man in this matter. Could one possibly win the love of a woman in our time in a better way than making her a parliamentarian, opening to her an opportunity to participate in lawmaking? In the past, one gave her a piece of jewelry, promised her horse and carriage or showed that she through marriage would reach a high social position, be presented at court and so on. Now one seeks her favor by getting her a wide sphere of influence.”

“Well, you may be partly right. But the female heart has not changed over thousands of years and will never be different. Do I have to say that to someone who is called a prehistoric poet?”

What did Oxygen do during these electoral preparations?

What line did Aromasia take?

Oxygen’s took from his conversation with his friend reason for several reflections that he had shunned hitherto. “Aromasia was showing a preference for the past when she put together such a composition as The Seasons,” he told himself. “Consequently, she's fallen somewhat under the sway of the Reversion Party. My conscience as a future-man prompts me to oppose her at the elections. But I can’t mount any opposition effectively unless I win the seat.”

For that reason he had, as he tried to convince himself, announced his candidacy. But was The Seasons his only reason?

Soon after the concert, Oxygen had received an unsigned letter. He could not guess who the author was. The letter contained something that fell into rich soil: after he read the letter, he was convinced that Aromasia should not be elected to parliament. It was then that he decided to run against her. He was in a hurry to put his decision into effect and thought that it admitted of no delay.

Was it only in order to serve his country that he wished to push aside the woman for whom he had felt the warmest affection?

That was the question he now asked himself. Would he, a future-man by conviction, one who profoundly despised futile feelings for the past — as he described ambition, envy, suspicion and jealousy — would he himself now act under the influence of one or all of these feelings?

Impossible! And yet, he feared that it was not only patriotism or craving for usefulness that had brought him to run against Aromasia.

Did he still love her?

Yes, for sure. And nevertheless he wanted to go against her intentions!

“Because she doesn't love me!” he exclaimed. “She allowed the crazy Apollonides to make the odoration The Seasons. He wrote the words for this antiquated composition. He has been co-operating with her. Therefore she can't love me any more.”

And then, matter-of-fact reflections came to an end again. Oxygen intoxicated himself on difficult suspicions and gloomy jealousy. In his inebriation, he vowed that he could not give in. He had to avenge being repudiated and deceived by the woman he had loved so much.

Jealousy and vengeful feelings existed in the 24th century to the same degree as in the old days, but these feelings no longer used knives or poison. Their weapons were parliamentary elections and suchlike. Apollonides himself would perhaps have been forced to admit that this was an improvement, although not very romantic.

But the legislative work? Would that depend on love or jealousy? Had it not in the past depended on some human weakness?

Aromasia fought against herself. She was brought up with the view that women and men were equal and that love never could weaken women's rights. But the old book she had happened to look into that evening at the party hosted by her old kinswoman, that book had directed her thoughts in a different direction.

Aromasia had been given a good education. Since its purpose was not only to develop her artistic talents but also to make her, like all other women, fit for public duties, Aromasia did not feel inferior when it came to participation in legislation. That kind of inferiority, as far as women were concerned, had not been known for centuries and was even less so during the period now in question.

To be sure, Aromasia was quite young, but youth was in the 24th century no obstacle to public service. On the contrary, it was even considered preferable. Youth was an age full of enterprising power and perseverance. It should not be permitted to disappear without being put to use.

That was at least the way of thinking in the later part of the 24th century, and it never occurred to Aromasia to call this view in question. But just because of that, a sacrifice would be much more important; a privation much more valuable.

The task of the woman is to do without, the old book said, and Aromasia's thoughts reverted over and over again to that statement. Would she perhaps submit to such a sacrifice in order to give Oxygen a proof of her love?

That was what she thought at one moment. At the next, she told herself that she loved Oxygen in a similarly warm and sincere way, even if she did not decline the honor of being asked to become a member of parliament. Oxygen’s behavior was irrational, and she, who loved him so much, ought not to support it. And yet!

Aromasia was in a most awkward state. What decision would she arrive at? She felt incapable of doing anything at all. Her ododion had been left untouched for days. She did not receive any visitors. She did not go out. All day long and late at night she sat immobile in her garden.

The days were clear and warm. Only now and then a cloud arose, and it was obviously artificial. Maybe it was manufactured by Oxygen? The cloud absorbed Aromasia's thoughts. They disappeared with it, but returned constantly. They dissolved with the mild rain that the cloud released on some field in the vicinity of Telge or on some big strawberry land on the other side of Rotebro.

Nevertheless, her thoughts at the next moment were the same again. They could not be destroyed as long as Aromasia was in this state. They were natural products of the struggle that raged in her mind, the struggle between her love and her dignity as a woman, as a human being.

To be continued...

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk