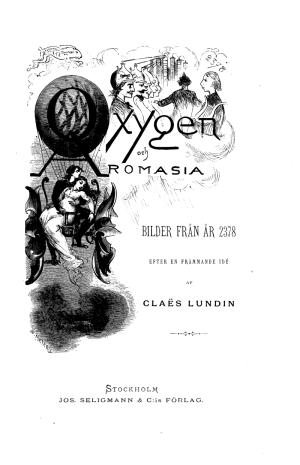

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 17 Chapter 18 appeared in issue 269. |

| Chapter 19: Nature Poetry and Starch |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

Some evenings after the banquet in Copenhagen, Aromasia was once again in her Aunt Vera’s parlour in Stockholm. Aromasia’s old lady friend was hosting a small party to celebrate the artist’s rescue and her extraordinary success in Copenhagen. Even Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar and Miss Rosebud were invited and did not miss the opportunity to attend.

Some evenings after the banquet in Copenhagen, Aromasia was once again in her Aunt Vera’s parlour in Stockholm. Aromasia’s old lady friend was hosting a small party to celebrate the artist’s rescue and her extraordinary success in Copenhagen. Even Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar and Miss Rosebud were invited and did not miss the opportunity to attend.

Since Aunt Vera had no respect for the two women, Aromasia was surprised to meet them at Aunt Vera’s place, but she guessed that the invitation was due to some specific reason, though Aunt Vera had not confided to her what it was.

Even Apollonides was amongst the guests. When he had no longer been able to follow Oxygen and Aromasia on their airborne journey and had safely escaped a bath in the storm-swept billows of Lake Vättern, he stopped over for a few days in the vicinity of the castle of Karlsborg. His intention was to glean from the romantic ruins themes for another heroic poem that might console him for Aromasia’s being spirited away.

The hero of the poem was himself, who in ardent verses sang the praises of the beautiful artist and painted the weather manufacturer in the darkest colors as a presumptuous titan who wished to snatch lightning from the sky, and who for years and years had gathered together cloud upon cloud but nevertheless had not been able to conquer the real storm that Nature itself hurled against the foolhardy.

After a couple of days of persevering work, the poem had been completed. And the author, who had learned that both Aromasia and Oxygen were once more in Stockholm, speedily proceeded there. He had just arrived when he was invited to the social gathering by Vera, who seemed to feel pity for his pangs of love. There he would find Aromasia, who was eager to express her gratitude for his sympathy after the accident in Gothenburg.

Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar seemed to be thinking of new intrigues. Oxygen’s renunciation of his seat in the Parliament might give her another chance to undertake the same activity as before, but Miss Rosebud did not seem to wish to use her any more. That was inexplicable to the plotting woman, and she began to find little Miss Rosebud too old-fashioned. And she could not understand why Miss Rosebud no longer wished to carry out her plans against Aromasia, even though Aromasia was still being eagerly courted by Apollonides and Miss Rosebud still cherished the same glowing love for the scald.

On the contrary, Miss Rosebud seemed to approach Aromasia. She regarded the artist with sympathetic, sometimes meek and, so to speak, regretful eyes. And Aromasia, who willingly forgot the display of dislike that Miss Rosebud had shown her earlier and who not know the cause of the accident in Gothenburg, responded to these humble eyes with kindness, and she answered with generosity the bashful words that accompanied this new behaviour. Miss Rosebud seemed to be very happy at that.

“There’s no doubt that she has good reason to be contrite to Aromasia,” Aunt Vera said, “but also to be glad that there was no loss of life at the concert in Gothenburg.”

Mrs. Sharpamn-Fulmar smiled arrogantly and spitefully, but Miss Rosebud doubled her respectful attentiveness towards Aromasia. However, this did not prevent her from experiencing an unpleasant feeling every time Apollonides seemed to extract an encouraging gaze from the artist. She now knew very well that Aromasia did not love Apollonides. But his continued attempts to win Aromasia’s love were hateful and painful to her.

The scald asked for permission to read aloud his latest work, but Aunt Vera intended to decline that offer without hurting the author’s feelings; he was as irritable as the ancient poets. Many of the present women were occupied with mathematical embroideries. That was something that very common in these days. By carrying on a conversation about this, the hostess avoided allowing Apollonides to recite a poem that most likely would only have made the writer an even bigger fool in the eyes of those present.

Aunt Vera was too humane to wish that people would make fun of one of her guests. She also knew that this latest product of a genius would include an attack on Oxygen, something she would not permit in her house.

The mathematical embroideries had succeeded the needlework, knitting and crocheting that constituted the female occupations of the past, when a group of ladies gathered for a good time with something other than dancing, music, or card-playing. It was also used in daily life within the family circle as a pastime as useful as it was pleasant.

Thanks to the work of prominent scientists, society could now perform unheard-of calculations, which in the past would have required a man’s whole life. Now with the integration machine, they could be executed within a few hours and without any mental effort. One continued conversing while the integration machine worked, and the machine made far less noise than the sewing machines of the past.

Now and then one glanced at the machine, looked at the numbers and the geometric diagrams and made a short mental calculation. Then the attention returned to the topic of the conversation, just as when people in the past counted the stitches when weaving a tapestry or knitting a pair of stockings.

In the midst of the discussion of mathematical embroideries, Oxygen entered to call on Aromasia. He had not had time to perfect his Will-subduer or to obtain enough diaphot before he left Copenhagen. Aunt Vera greeted him with her usual kindness, but Oxygen only had eyes for Aromasia, who also offered him her hand but did not appear to give him reason to begin a more intimate conversation.

On Oxygen’s entering the room, Apollonides turned pale and showed vehement mental agitation, but he soon cut in on the conversation that Oxygen had begun with Aromasia and some of Aunt Vera’s other guests. Everything that Oxygen said was contradicted by the poet or used by him as an object for mocking remarks.

However, those weapons were soon turned against the attacker, and Oxygen had the laugh on his side — at least with everyone except Vera, Aromasia, and Miss Rosebud. But the conversation also took a serious turn.

They still talked about past and present, a usual subject of conversation where Apollonides took part; and he always stood up for the past with the same fervour. As he did now.

He praised the days when man still understood how to appreciate the beauty of Nature, and in looking at Nature felt the greatest joy. He regretted that people no longer knew the existence of this perception and no longer cared about the flowers in the ground. Gardens hardly existed any more except on the roofs of tall buildings. Forests were more or less gone, and one could never again experience the solemn feeling that had touched the hearts of men in the past as they heard the sacred whispering of the treetops in the solitude of the woods. Soon the farmers would no longer walk under the open vaults of the sky, between swaying ears of corn, rejoicing at the hope of rich harvests.

“What do we have now that enlivens the mind and fills the heart with fresh feeling?” he exclaimed in a melancholic way.

“We have starch factories,” Oxygen replied, “albumin factories, laboratories that provide for the healthy and inexpensive food for the human race.”

“But the green coating covered with magnificent flowers, the most beautiful adornment of the earth, are disappearing. With them, our breath of life will disappear, the breath of life that already now largely must be taken from the oxygen factories. Mankind will perhaps never more experience hunger, at least not when it comes to the stomach.

“But who can slake the idealistic hunger, and above all the desire for a piece of free Nature? Furthermore, where do we find any great feelings? Where are the tragic conflicts? Where has beauty gone? The compensation we look for in brain-organs is indeed far too poor.”

“Now once again you’re unfair and embittered,” Aromasia put in. “You don’t want to acknowledge the great merits of our time. There is no lack of grand and beautiful feelings even now, and we will probably not escape your tragic conflicts.“

“What can be more silly and ridiculous than all this moaning about the disappearance of green vegetation!” Oxygen exclaimed. “The vegetal world certainly had the right to exist in the past, and there was a purpose for that as long as one needed plants for food and the regulation of the atmospheric conditions.

“But now our needs are better provided for. Why, then, should we let that romantic, greenery with all its gaudy spots take away a place that is needed for more useful purposes? Plants will always retain their historic significance, but as such they have once and for all been exiled to the field of palaeontology and scientific collections.”

Apollonides could not restrain a cry of horror and profound resentment, but his outburst only brought about smiles and a horse laugh from Oxygen. “Everyone who defends the useless vegetal world,” Oxygen explained, “belongs to the kind of men who are going to be abolished. And I must confess that I consider it an obligation for mankind to proceed fearlessly even if it is over the dead bodies of these people. They’re vermins in our society.”

“Oh, Oxygen,” Aromasia exclaimed disapprovingly. Miss Rosebud turned away in disgust from Oxygen and tried to encourage Apollonides with languishing looks.

“I can prove what I’ve said through rational calculation,” Oxygen assured.

Apollonides sat ghastly pale and stared at the horrible, dirty weatherman. Neither of them had forgotten their old loathing for the other. A duel in the ancient way was not customary any more, and not even Apollonides thought of that, but at the same time he felt that he and Oxygen could not possibly live simultaneously on the same planet. That feeling also seemed to have taken root with Oxygen.

* * *

The party was waiting for the promised rational calculation when another visitor was announced. Bank director Giro entered with his young son, the promising male heir to all the possible joint-stock companies in the world.

The new arrival made known that he was on his way to another quarter of the town, since he had come from Gothenburg in order to put his son in the new brain school in the suburb of Södertälje. But he could not fail to pay Mrs. Vera a visit and find out if Next Week’s News was right when it said that Miss Ozodes now would stand for Parliament in the same district where she had been nominated, although she had not received a majority of the votes. The district would again elect a representative, since the elected person had resigned.

Aromasia immediately declared that she this time would devote herself more persistently to the election campaign. The reasons that had influenced her conduct last time did not exist any more.

Giro said that he was most pleased with this explanation and assured that he had a joint-stock company in mind that would assure Miss Ozodes’ total success. When he had finished discussing what he called public matters, he thought that he also should ask about the accident in the Örgryte block and the wonderful rescue of the artist.

He did so even though as a good businessman he did not readily spend time talking about things that had already happened. His eyes were always directed toward things to come, especially since they could give rise to new joint-stock companies.

Once more the conversation turned to the same topic that had been discussed before Giro’s arrival, and the banker declared himself to be in total favour of the opinions expressed by Oxygen.

“But,” he added, “there’s no reason to think we will have made real progress until the new law of instruction has shown how beneficial it will undoubtedly be.”

“The new law of instruction?” the others exclaimed with questioning glances.

“Have you not heard about the law?” Giro asked with surprise, and one could hear certain superiority in his voice. “Stockholm doesn’t really keep abreast of the times, I fear. The law was legislated yesterday evening by parliament and comes into force tomorrow. It’s an excellent law, but I would like to hear what the old, romantic emotionalists think of one or two of the law’s provisions.”

All turned their eyes at Apollonides, as if they expected that the scald would appear and express the views of the old, romantic emotionalists. But he was no longer in the room. He had withdrawn without anyone noticing it. Not even Miss Rosebud had observed his disappearance, even though it had not been many minutes since she had been trying with her eyes to attract his attention or inspire him with comfort and encouragement during Oxygen’s merciless attack.

When Apollonides was no longer to be seen, nobody thought of him any more; nobody except Miss Rosebud, who conceived a gloomy suspicion and soon left the party as well.

Proceed to Chapter 20, part 1...

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk