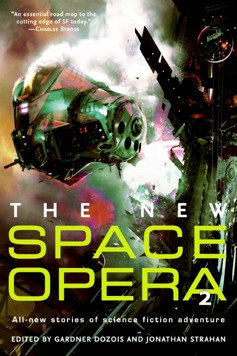

Gardner Dozois & Jonathan Strahan, The New Space Opera

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

The New Space Opera Gardner Dozois & Jonathan Strahan Publisher: Harper-Collins, 2007 Length: 515 pages ISBN: 978-0-06-084675-6 |

So first, how do Dozois and his fellow editor Strahan define new space opera? Or even space opera? It’s romantic adventure, according to Dozois, set in space and told on a grand scale. I think that’s a good definition.

We know what opera is, whether you’re a fan of Wagner or his trilling Italian rivals. It’s emotion writ large, more than anything else. Did you weep the first time you listened to Mimi’s dying scene in La Bohème? The young man behind me at the opera house did. He sniffled at the start of the scene, and by the last throb, couldn’t pretend he had a cold any longer. He was frankly bawling.

So Dozois and I are in agreement on at least what defines space opera. Space opera’s been around long enough that Dozois can quote Wilson Tucker’s sneering 1941 definition of “the hacky, grinding, stinking, outworn space-ship yarn.” But then, as Dozois points out, along came Jack Vance, Poul Anderson, A. E. van Vogt, and many other worthy stars, who painted the genre with more luster.

Space opera suffered a drought period then until the mid-1990’s, when what Dozois calls the new space opera appeared. The short stories in this book all reflect Dozois’ choices in the genre. So how do his choices stack up against the old space opera — or his definition of space opera, for that matter?

I had a mixed reaction. Almost all of the stories in this collection are good. Compared to the old space opera, most tilt far more heavily on actual technology and science (reflecting the editor’s tastes). I learned a bit more than I wanted to about wormholes in one case. Greg Egan’s “Glory” started out with such detailed scientific geek-speak I almost skipped the entire story. But once that was off his chest (the presenting of his credentials, so to speak), the story finally became interesting for its human side, and I’m glad I read to the end.

But the technology rarely overwhelms, for the most part. And we’ve got span and scope in these stories — galaxies traversed, thousands of years speeding by, humanity as a grain of sand on the beach of the universe.

A few stories reflect the modern trend to protagonists who just aren’t likeable. One is a less-than-intelligent assassin who should have done her homework (“Saving Tiamaat”). A few are so strange and bizarre, who cares? (I couldn’t get into Ian MacDonald’s three friends, I’m sorry). Peter F. Hamilton’s “Blessed by an Angel” is ugly enough to make you wince.

But then we have the protagonists who would make that soft-hearted young man sniffling over Mimi react: the romance between a young farmer and a nomadic woman, separated by far more than a stone wall; a visitor who gives a little girl flowers and endures the sorrow of seeing the sweet child became a ruthless adult; an eccentric little man who brings Edgar Allen Poe to rough-and-tumble Martian miners; a future Scheherazade telling the Emperor stories to save humanity and her own neck; a hapless Lothario whose romantic exploits and agreeability only get him into more trouble; a troupe of actors, bringing the Bard’s works to the rulers of the universe.

Thus my favorites in the collection were the ones involve us in the human element: Kage Baker’s “Maelstrom”; Tony Daniel’s “The Valley of the Gardens”; Mary Rosenblum’s “Splinters of Glass,” Kress’ “Art of War.” And the most space-operatic in the collection, that tale of the dreamer who brings a musical “Maelstrom” to Mars.

For again, what is opera, if not emotion and pathos writ large? The stories that work here are the same ones we’ve always told. Human emotions and human dilemnas. Science is only the frame around the mirror reflecting a face that eternally fascinates us.

Space opera may be tragic, it may be joyful, but it should have feeling. Authors in this collection often confuse scientific scope with emotional scope. It’s as if the original space opera were writ in lurid color; Dozois’ New Space Opera is in black, white and grayscale. That over-the-top zest is mostly missing.

But many of the stories in this collection get space opera right. And though some don’t make it as true space opera to my mind, the collection is still excellent. Highly recommended. Get it.

Copyright © 2009 by Danielle L. Parker