Alfred Bester, a Science Fiction Pioneer

by Bertil Falk

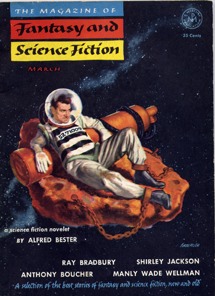

Visiting a second-hand bookshop during a visit to Stockholm, I bought thirty-six back issues of Fantasy & Science Fiction, among them the March 1954 issue (vol. 6:3). It turned out to be vintage stuff. Names like Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson, Anthony Boucher and Manly Wade Wellman speak for themselves, four writers reflecting different sides of fantasy and science fiction.

Fantasy & Science Fiction,

March, 1954. Cover by Kirberger |

In Issue 6 of Bewildering Stories, Thomas R., a contributor since Issue 1, wrote about Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (early title: Tiger! Tiger!). Among other things he said:

“The main character for me was a disappointment. I had heard for years of Gully Foyle yet mostly he was just crude and cruel. A single-minded opportunist, but more importantly something of a bore. For some reason I never saw what was supposed to be all that interesting about him except the author’s occasional efforts to slam into you that you must find him interesting.”

My reaction to this statement is that those who had told Thomas R. for years about Gulliver Foyle must have hoodwinked him, planting wrong expectations in his mind. The Stars My Destination depicts how an indolent, sluggish and average man, a constitutional opportunist, is forced out of his hibernation. It happens when he is subjected to something he experiences emotionally — and not at all intellectually — as an act of treachery.

The mental shock triggers him into what probably is the most magnificent post-traumatic stress disorder in science fiction literature. His life is turned into a scream for revenge; of course he is crude and cruel. That was Bester’s objective.

Bester modelled the story on the archetypal revenge story The Count of Monte Cristo (1845) by Alexandre Dumas, père. Dumas “stole” the story from Jacques Peuchet’s The Diamond and Vengeance (1838). Peuchet “stole” it in his turn from a real-life event.

Alfred Bester’s alleged efforts to “slam” into us that Gully Foyle is interesting is rather a figment of Thomas R’s own imagination and interpretation. For exactly what in the text justifies such a statement?

One of the many important things about The Stars My Destination is that it is precipitously existential, psychological and philosophical. But those qualities apply more to the structure of The Stars My Destination than The Count of Monte Cristo. The phenomenon that Alfred Bester utilized in order to tell his story can be described in one word: teleportation, though Bester called it “jaunting.”

Charles Fort coined the word teleportation in his book Lo! (1931), where he wrote: “Mostly in this book I shall specialize upon indications that there exists a transportory force that I shall call Teleportation.”

Teleportation involves the transportation of an individual or object from one point to another without waste of time, without delay; in other words: instantaneously! You start in Moscow and you arrive immediately in London. No time-consuming flight, something devoutly to be wished for. Teleportation became a standard phenomenon in science fiction.

Gulliver Foyle displays hidden mental resources, when in a towering rage he literally blasts himself out of the inexorable snares of existence and in full-blown panic crosses the Solar System like greased pig. He teleports not only in space but also in time.

But Alfred Bester did not only use teleportation as a Fortean means of transport, he used it as an integral part of the plot itself. And that is most certainly the reason that the magic has not been repeated. You cannot easily echo The Stars My Destination without using its very structure as well as the action; they are inseparably intertwined.

Alfred Bester was exceedingly versatile. He worked on comic books, wrote radio scripts, reviewed books for F&SF and wrote travel stories for Holiday. He penned mysteries, science fiction, and mainstream fiction. A genuine professional, he was good at whatever he did, on assignment or on his own.

He not only knew what was expected from him when he wrote for The Shadow radio show, he crossed the borders of formula-written stuff in his own stories. His science fiction short stories over the years were all very special and original, such as “The Men Who Murdered Mohammed,” “Star Light, Star Bright,” “Hobson’s Choice,” and “Fondly Fahrenheit.”

Alfred Bester’s first famous novel was the science fiction detective story The Demolished Man. It is brilliant but structurally not as explosive as The Stars My Destination. However, imagine my surprise when I read Alfred Bester’s contribution to the aforementioned issue of F&SF, the novelette “5,271,009.” I may well be wrong, but as far as I can understand, this novelette does not belong with his more famous yarns; however, it has that structural innovation that marks Alfred Bester’s science fiction.

“5,271,009” a.k.a. “The Starcomber” was probably written between the two novels. It was in any case published between them. The structure is perhaps, perhaps not as perfect as in The Stars My Destination, but it is different from mainstream. In a way, “5,271,009” is even more astounding than Bester’s two most famous novels.

“5,271,009” is like a system of unpredictability, but Bester did not do things by chance. There’s method in the madness of “5,271,009.” Gradually, the original surreal impression of the novelette disappears and the outline of the story becomes more and more tangible as Bester lets Jeffrey Halsyon experience eternal existential equations. The number 5,271,009 takes the shape of a catalyst symbolizing man’s innumerable and frightening decisions.

“5,271,009” can be perceived as a kind of 20th-century analogue to the medieval play Everyman. Bester permits the self-assured individual Mr. Aquila, who is a mix of “two parts of Belzebub, two of Israfel, one of Monte Cristo, one of Cyrano,” to psychoanalyse mankind, which is represented by Jeffrey Halsyon. And Halsyon himself could be a preliminary study for Gulliver Foyle. The part where Halsyon drifts “alone in space, a martyr, misunderstood, a victim of cruel injustice” forebodes Gully Foyle’s — and reflects Monte Cristo’s — similar predicament.

Alfred Bester in Stockholm, 1975 |

The sequences of “5,271,009” are to the point and not seldom hilarious. When rereading the story I always find new things to ponder on. What makes “5,271,009” a coherent whole is the fact that it is a story of a man reluctantly coming of age. That goes for mankind as well as for Jeffrey Halsyon.

Alfred Bester’s science fiction is not only worth reading, it is also worth studying as a model for aspiring writers. Bester is an author who tried new ways.

Copyright © 2009 by Bertil Falk