“In the Midst of Hell”

Worst and Best Memories of India

by Bertil Falk

Indira Gandhi has been murdered!

On October 31, 1984, I was awoken by my friends in Vikas Puri — a suburb of New Delhi — and then things began to happen quickly. The assassins were Sikhs, the Prime Minister’s own bodyguards. They were avenging Operation Blue Star, when Harmandir Sahib, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, was attacked by the Indian army.

During the next three or four days there was a hue and cry after Sikhs in the Indian capital. Murderous gangs traversed the suburbs of New Delhi; they consisted of young men belonging to the slain Prime Minister’s Congress Party. The ultimate outcome was three thousand murdered Sikhs, two of them lying outside our house. But it should be said that the Hindus in our vicinity protected their Sikh neighbors.

* * *

|

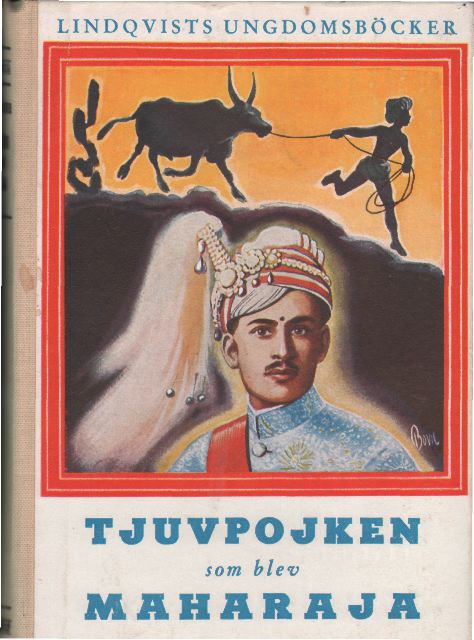

Per Westerlund came from Söder, the working-class area of the Swedish capital Stockholm. He was a kind and likable man. While visiting the island of Öland at the age of 18, he found salvation — or as they say, he was born again — and he served as a lay preacher in Norrland, the northern part of Sweden.

He became the Secretary of the KFUM (YMCA). In this capacity he became the first Swede to travel by car all the way to India, in the 1930’s, where he attended a jamboree. He also stayed with Swedish missionaries, who were working among the caste of thieves, and he made a heroic attempt to climb the Kanchenjunga.

During WW2, I followed the course of events in India, where the Gandhian independence movement was active with non-violent activities. The Quit India movement, in 1942, was the most powerful.

I took the train to Stockholm once every week and went to the movie theater called Spegeln (The Mirror), where in daytime the so-called Dagens spegelbilder (The Mirror Pictures of the Day) were shown. They consisted of newsreels from the Swedish SF, the American Paramount, the German UFA and many others. They were mixed with documentaries and with cartoons by Walt Disney and Max Fleischer and other producers. The newsreels from India were not really overshadowed by the world war. I rather experienced them as a part of the world situation.

My interest in India never disappeared. When I was 44 years old and worked as the night reporter on the graveyard shift at the daily newspaper Kvällsposten (The Evening Post) in Malmö, S.M. (Sven Magnusson), the editor of the New Age periodical Sökaren (The Seeker) asked me if I could write an article about the alleged tomb of Jesus in Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir in northern India. I replied: “I’ve never been to India and I’ve never seen that tomb, but you’ll hear from me again.”

No sooner said than done. I went to India in 1977 and I still remember the hot, humid air that swept into the cabin after our landing in Bombay. On board the flight I met an animal dealer and adventurer from Trelleborg, who told me how to behave and dress while in India. He took me to a zoological park and a circus. It was fascinating to hear him discussing buying elephants in exchange for apes, lions or whatever.

I took a train via New Delhi to Jammu Tawi, the winter capital of Kashmir, and since that was the end of the line I took a bus that transported me through a tunnel in the Himalayas to Srinagar. There I saw the tomb, which according to the Ahmadiyya Muslims (considered to be heretical by other Muslims) is the last resting place of Jesus. And I made friends for life in Srinagar.

* * *

Then I returned to New Delhi, where I arrived on the morning of my last day in India. Indira Gandhi had been swept from power as a result of suspending democracy and invoking an emergency, with all the opposition leaders jailed. I went to her residence and asked her people if I could interview her for my newspaper. Call us back later, her rank and file said.

I did so and was granted forty minutes with the ousted lady. I did not get it then, but when I look back in the rear view mirror, I understand that the most important question I asked her was: “Why did you put an end to the emergency and appeal to the country?”

Indira Gandhi’s reply was: “In a democracy you cannot maintain an emergency as long as you like.” I have not seen her give that explanation anywhere else, but on the other hand I have not seen everything published regarding her.

She said about Morarji Desai, a man she had jailed and who succeeded her as the Prime Minister of the world’s biggest democracy, that he was shrewd. She immediately added: “Don’t quote me on that!” I did not — until now.

Bertil Falk with Morarji Desai

|

Morarji Desai had the habit of drinking one liter of his own urine every day. When I called that habit into question, he told me that it was a most efficient remedy. I can prove his assertion, for I still keep the tape of the interview. As far as I can understand, he considered it a preventive medicine. He lived to the age of 100.

Bertil Falk with Indira Gandhi

|

It was impossible to get out of Vikas Puri after the murder. And when two slain Sikhs lay outside our house, I experienced something that I had never experienced before and never since. A kind of irresistible dread arose within me like a breeze of some ancient and atavistic memory coming out of the distant past from a time even before our species existed.

Incapable of doing anything, I lay down and tried to empty my mind. By using Zen meditation I succeeded. The overwhelming fear disappeared. That is the only time in my life that I have actually had a tangible result from my meditation training.

I did make a couple of attempts to get away from Vikas Puri. When we came in a motor rickshaw to one of the two Ring Roads, burning cars were seen here and there. The closer we came to the hospital where the slain prime minister had been taken, the more angry young men appeared. They hit at the motor-rickshaw with cricket bats and told the driver to stop. They looked into the rickshaw, and when they saw we were not wearing Sikh turbans, they let us go.

The driver was jumpy. He wanted to go back. I protested and said that there was no danger, since we did not wear Sikh turbans. But the driver said: “When they start killing people, they don’t care who they are slaying.” He refused to drive on, and we returned to Vikas Puri.

The next day, two friends and I walked from Vikas Puri to neighboring Hari Nagar. A lot of people were out on the streets, pillaging Sikh shops, stealing TVs and furniture. Some shops were even set on fire. Not a single turban was seen. I tried in vain to get hold of a telephone.

The third day I succeeded in that effort and called a member of the Swedish embassy. A young Swedish fellow, who just had arrived in India, answered the phone. He promised to tell the embassy that I wanted assistance to get out of Vikas Puri. Later, a white Volvo with the Swedish flag came and stopped outside the house in Vikas Puri. The roadblocks were opened for us and I checked in at a five-star hotel and booked a call to the editorial office of Kvällsposten in Malmö.

|

That became the headline on the news-bill as well as on the front-page, though this spontaneous commentary was not in the text I read out; but Jakob, as we called him, ever the clever newsman, thought that this exclamation summed up the situation in a nutshell.

* * *

I took an interest in a personality in the history of India: Feroze Gandhi, the husband of Indira Gandhi, the father of Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi, the father-in-law of Sonia Gandhi and Maneka Gandhi as well as the grandfather of Rahul Gandhi, Priyanka Gandhi and Varun Gandhi.

Feroze Gandhi was a member of the Lokh Sabha, the House of Commons in the Indian Parliament, and although he was a member of the ruling Congress Party he was akin to an unofficial leader of the opposition against his father-in-law, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Among other things, Feroze Gandhi caused the resignation of one of the ministers of his father-in-law’s government.

Though most Indians know of Feroze Gandhi, he is nevertheless nowadays mostly forgotten and definitely marginalized, but his supporters in the past were of the opinion that had he been alive, he — not Indira Gandhi — would have been the third Prime Minister of India.

I am not sure of that, but he was a most interesting person and I have dedicated a lot of time and effort to collecting information about him and will hopefully be able to produce a biography in 2012, to mark the centenary of his birth.

* * *

As for Per Westerlund, he too is forgotten and marginalized. When passing between Stockholm and Trelleborg I stopped my car at the New Graveyard in Nyköping. I discovered that his and his wife’s grave had been leveled with the ground and their gravestone taken away. In that way the memory of a Swedish writer is rapidly obliterated —though there is at least one person who still reads his books. And without him, these memories and many of my other Indian memories would never have come to life.

Copyright © 2010 by Bertil Falk