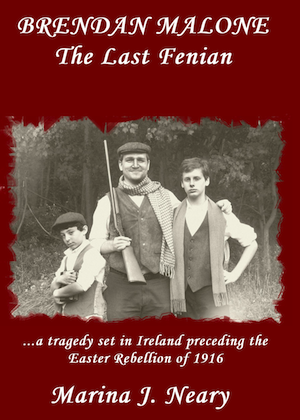

Marina J. Neary, Brendan Malone:

The Last Fenian

excerpt

Brendan Malone: The Last Fenian Publisher: All Things That Matter Press (January 2011) Paperback: 206 pp. ISBN: 0984629742 978-0984629749 |

The Freak Show on Frankfurt Avenue

(Dublin, 1908)

The stain glass door to the balcony slammed, separating the noise of the festivity inside the villa from the humid March evening.

Left alone, the young girl bent over the carved balustrade and glanced down with a sort of sneering curiosity at the students who apparently were more than eager to resume the interrupted conversation with the ravishing brunette.

“Please, explain once again,” one of them spoke, struggling to articulate more or less clearly. “The Polish Count isn’t your father?”

“Only in spirit, my lamb!” she chirped in response, grasping at the opportunity to talk about her unconventional origin, which must have served as a source of tremendous pride for her. “It is a fact which we both regret at times. Oh, Count Markiewicz is a gallant, humorous, artistic soul. You must see his oil portraits! I am still trying to persuade him to donate a few pieces to the college gallery, but he will not relinquish any. The man’s modesty is infuriating! He also writes plays and brings them to stage himself. Otherwise, why would my mother have married him? They met at a ball in Paris ten years ago, long after I was born. I assure you, he loves me no less than he does Stanislas and Maeve, though in blood we aren’t related.”

The exhausted gramophone behind the curtain of the ballroom began spitting out bits of Oginski’s polonaise. The silhouettes, that until then had been wavering chaotically, began forming into a semblance of a line. Count Markiewicz’s guests were preparing to celebrate their Slavic glory in the heart of an Irish city.

“If so, then who’s your real father?” the student continued interrogating her, which she did not seem to mind at all. “Confess! Who is the lucky bastard who created a beauty like you?”

The girl tossed her head up, as if addressing the moon.

“My father,” she droned with almost theatrical pathos, “is a devoted servant of his land — our land, that is...”

The student was in no state to solve riddles. For one, he did not know how to interpret the string of the bestial endearments sent in his address. First he was called a piglet and then promoted to a lamb. What animal would he become by the end of the night? He was secretly hoping to be called a stallion.

“So, is he in that Gaelic League with that fellow by the name Pearse?”

Dropping the names of political activists left and right would surely impress the young lady. The drunken student was incredibly pleased with himself for having even remembered Patrick Pearse. Now the count’s stepdaughter would know that he was not merely killing time at University College. No, sir! She was not the only one who appreciated high culture.

“Silly pup!” the girl laughed, causing the student to pull his head into his shoulders. He had been demoted to a pup. “The Gaelic League requires formal education and some serious understanding of poetry, which aren’t the strongest merits of my father. Still, he is learned enough for the Republican Brotherhood.”

The last two words were delivered in menacing whisper and accompanied by a conspiratorial wink.

The student let his jaw hang, as if someone had punched him in the chest.

“A Fenian... So, you’re one of us then!” He shook the empty whiskey bottle over his head triumphantly and then spun around to face his companions. “Hear that? Her father’s in the Brotherhood, just like mine.”

“And I intend to spend the summer with him,” the girl continued proudly. “As soon as I finish paying my duties to the society...” She nodded negligently towards the lights and the wavering shadows behind the balcony door. “As soon as I dance the same polonaise ten times over and let every old man pinch my cheek, I’m off to the shores of Shannon, to be with my natural father. Perhaps, I’ll meet you there some day.”

That was the moment when the student’s legs resigned on him. He dropped to his knees, on the pavement, assuming the archetypical Romeo pose, his eyes still fixed on the balcony. At that stage of intoxication he could see only a vague figure in white, all entwined with black hair. His mind proved out to be no less treacherous than his legs, and the student filled the streets with a savage howl, clasping his hands to the chest, just like the early film actors did.

“Blast me! Where the hell are the words when I need ‘em? Why can’t I be a poet? Wouldn’t I cherish you if you were my wife! Let me hang if I lie. Dadaí raised me a patriot. Do you even know my Dadaí? Oh, he’s the finest landlord in the Tulsk village! He owns two farms, a potato field, and a whole herd of horses like you can’t find anywhere else. He also got more rifles and sabers than the whole British army! And all that can be yours, a stor... Just say a word.”

The girl listened to his ranting with an air of superficial fascination. She seemed accustomed to such conduct from men. Drunken speeches were clearly no novelty to her, even though she was standing on the balcony of the most fashionable villa on Frankfurt Avenue, wearing in a goddess gown of white silk, with golden bracelets of the most meticulous craft clasped around her wrists. She blended quite well into the atmosphere surrounding her, yet one could sense, there was another place on this earth that would make her an even more welcoming home, another society that would find her qualities even more admirable.

In all honesty, her behavior was a bit too unbridled for a true aristocrat. She laughed with impermissible sincerity. The clumsy tricks of the drunken student that would have repulsed any young lady only amused the Count’s stepdaughter. Irresistible in her jovial audacity, like a heroine from a folk tale, she needed no more than what nature had given her to win instant affections.

Suddenly, the girl bowed even lower over the balustrade, allowing the students to catch a glimpse of what was hidden beneath the shoulder ties of her goddess gown. She held onto the slippery railing with the confidence and the agility of trapeze acrobat, kicking up her feet in golden sandals, her neck arched.

“Wait now, what’s your father’s name?” she asked squinting quizzically. “Could it be Brendan Malone?”

Once again, the student wavered in awe.

“I’ll be damned... How did you know?”

“Oh, it wasn’t difficult at all,” she replied, straightening out abruptly, thus depriving the smitten boys of the bliss of staring at her bust worthy of Athena. “Who else could have a son so boastful? As it turns out, my dear, our fathers are tight friends. That means I know you too. And you ought to be ashamed, young Mr. Malone. You have a bride at home, a sweet, trusting, primitive soul. What if she were to see you now and hear your serenades addressed to another woman?”

The student slapped himself on the forehead and let the palm of his hand drag slowly across his flushed face.

“Heavens, that’s true too,” he muttered in horror. “I’m drunk, a stor, deadly drunk. Satan twisted me, I swear.”

“Surely, blame it on poor Satan!” The girl frowned skeptically. “And does he twist you often? Do your other lady-friends know about Caitlin?”

“There are no other women, I swear!” he shouted in self-defense. “And I don’t drink often. No money, see?” He turned his pockets inside out and let them hanging like a pair of donkey’s ears. “Today I spent the last penny of my stipend, but only in the honor of St. Patrick’s. That would be a mortal sin not to toast our christener.”

“I see now,” the count’s stepdaughter concluded with a nod. “St. Patrick and Satan are on the same side for once. They united to empty your pockets. How convenient! I bet the crooks at the theology department would love to hear that. What other tall-tales will you have for me?”

“This is no tall-tale! What I told you of my father is all true. He’s a patriot and raised me to be one.”

“We shall need a proof of that,” the girl demanded, tapping the balustrade. “Why don’t you sing about the Three Manchester Martyrs right on this spot?”

The student crumbled with embarrassment.

“I confess, I can’t remember the words.”

“I don’t believe that bosh for a minute!” the girl defied him indignantly, wrapping her bejeweled fingers around the neck of the marble lion. “You know the words by heart. Your father would’ve never sent you off into the world without them.”

“In that case, suit yourself, dear lady!” The student replied, abdicating and threatening at the same time. He locked his hands and began cracking his knuckles, as if they were going to play a major part in his performance. “You asked for it. Now cover your ears.”

He pulled himself up from his knees in one labored motion, tore his tweed coat off, waved it above his head and began howling:

God save Ireland, cried the heroes.

God save Ireland, say we all.

Whether on the scaffold high

Or the battlefield we die.

He repeated the refrain a few times, to the indescribable delight of the girl who almost fell over the banister laughing and even greater embarrassment of his younger brother who had been standing under an elm tree all the while.

The younger boy emerged from the shadow, seized his brother by the belt loops of his trousers and pulled him out of the limelight.

“Hush, for God’s sake, before the guards take you in!” he scolded the hapless singer. “You must be mad to sing such songs, in such a place and in such an abominable voice! God be my witness, this is the last time I escort you on your drunken expeditions!” he continued reprimanding the drunken patriot. “Instead of preparing for the exams, and I must keep watch over you instead! Dissertations do not write themselves, you know. Next time I shall let the guards arrest you. A night in prison would serve you right. Wouldn’t Dadaí love to hear that?”

The third student, a mutual friend of the brothers, lingered beneath the window.

“Gentle lady,” he started in the most mournful tone. “Dazzling lady, I’m starving here, you see. Haven’t had a morsel in my mouth in two days. I can hardly stand on my feet. What a sweet life you’ve got here: a fine house, a kitchen full of cooks. And what are we to do, away from home? Wouldn’t you have an apple or a bread crust for a famished scholar?”

“A bread crust for a famished scholar? Would that be all? Why not ask for caviar and capers in a pastry shell?” She laughed and disappeared inside the villa.

The boy stared at the balcony longingly, sighed, preparing to leave, but the girl reappeared a few seconds later, carrying a basket covered with a linen towel.

“Here’s a modest treat,” she said. “Yes, my handsome stallion, you may kiss my hand, as it was done in the better times that neither one of us has been fortunate enough to witness. And in the future don’t fill an empty stomach with cheap beer. It never hurts to know your limits. Now, hurry on, before you lose sight of the rest of the herd.”

The basket contained freshly baked soda bread with raisins and caramelized cranberries, a triangular wedge of cheese, a few winter apples left over from last year’s harvest and an assortment of Dutch chocolates wrapped in jewel-colored foil. The student thanked his benefactress with a clumsy bow and pursued his classmates as swiftly as his legs allowed.

Meanwhile, the two brothers were on their way back to Stephen’s Green, their arms wrapped around each other’s shoulders.

“You don’t know how weary I’ve grown of Dublin,” the eldest one whined melancholically, struggling to keep balance and clinging to his sober guide. “How I loathe the city! I drink just to forget where I am.”

“Only two more years,” the younger one tried to cheer him up. “Wait at least for your diploma.”

“Why wait? What am I to do with a diploma? What the deuce do I need Aristotle for? You’re the one with an ever-fermentin’ brain, so you deal with the dead bastard. Perhaps, you’ll make a scholar one day, but I’ll never jump out of my rough potato skin. Nor do I desire it. I’d rather go home to Dadaí and marry at last. I go mad without my girl. Don’t you know, that’s why I act like a lout?”

“And you do it so well,” the younger one laughed. “For that alone you deserve a diploma. Recall how Dadaí told you to look after me? Did he ever fancy that the opposite would happen, that our roles would reverse?”

“Oh yes? Count the times I’ve saved you from the bullies!”

“That was fifteen years ago. Count the times I saved you from the guards. All those nights you would’ve spent in jail if I hadn’t been around.”

“I know,” the eldest boy mumbled, admitting to his inferiority, and hung his head even lower. “Every day I thank the Almighty for such a brother. Just please, don’t tell Dadaí ‘bout what happened tonight.”

“Why shouldn’t I tell him? He’d be mighty proud of you. Tonight you acted like a true patriot. You remembered the words and the tune of the song, and you were sober enough to perform it. What else can be expected of you? It’s a shame Dadaí wasn’t here to listen.”

Copyright © 2011 by Marina J. Neary