My Salieri Complexby Marina J. Neary |

|

| part 1 |

University College, London, 1884

“Awake, Samuel! Boarding with a genius will not transform you into one.”

That was the voice of reason, which guided me through most of my career. Yet another voice, one of superstition and vanity, tried to persuade me of the opposite. How I wished to believe that a fraction of Jonathan Griffin’s brilliance could project onto me if I only spent enough time in his vicinity! I fancied our brains resembled two communicating vessels, with grandiose theories and mysteries passing between them. Little by little, that venomous swamp of self-flattering fantasies sucked me in.

Griffin, a native of Cardiff, was almost three years younger than me but only one year behind in his coursework. He transferred to University College in the autumn of 1883, allegedly to study medicine. I emphasise the word “allegedly.” From the very beginning I had serious doubts that this man had any intention of treating patients for the rest of his life.

As I learned later, medicine was the profession of his father’s choice. Griffin feigned compliance only to gain access to London’s best library and laboratory. He took most interest in optical density and refraction index, two topics that had very little to do with medicine.

We enrolled in the same physics seminar led by Professor Handley, my intellectual father, who promised me an assistant’s position after my graduation as well as the hand of his daughter Elizabeth. Everyone in the department regarded me as Professor Handley’s heir, the future king of the laboratory. At least that was the case until Griffin’s arrival.

In one week this eighteen-year old boy with a Welsh accent toppled the hierarchy that had been in place since my first solo demonstration in 1881. When Griffin entered the lecture hall, all chatter would cease and then turn into a collective sigh of veneration.

It happened so quickly that I did not even have enough time to grow suspicious, or indignant, or bitter. He snatched my invisible crown and placed it on his perfectly shaped head, atop a cloud of snow-white curls.

Griffin was the only albino I had ever encountered. At first he struck me as a member of an entirely different race, one that Darwin and Kingsley would declare as superior to their own, a race untainted by unnecessary pigment. Later I learned that the condition had its disadvantages. Griffin’s eyes, garnet-red, were extremely sensitive to the light, obliging him to wear tinted spectacles and a hat when out of doors. Between those eyes a permanent crease was forming, growing deeper by the month. I studied that crease furtively, as if it were some hieroglyph, a clue to the mysteries of his mind.

* * *

As a child I suffered from respiratory distress. The slightest physical exertion caused me to pant and wheeze, cutting me off from the games of my sturdier peers. No, they did not taunt me. They simply refused to acknowledge my existence. At the time I would have preferred open ridicule to utter indifference.

I found consolation in corresponding with Robert Louis Stevenson, who had also had a “weak chest” and spent much of his childhood in sickbed. He had shared with me the early drafts of his novels and poems. His bewildering adventures distracted me from my affliction, provided me with an opportunity to step out of my treacherous, uncooperative body. By the age of sixteen I was reconciled to the thought that I would have no companions save for the merry crew of the schooner Hispaniola.

My position changed when I came to University College and discovered that in matters of intellect I surpassed most of my peers. Suddenly, my physical infirmities became inconsequential. A former outcast, I became the most sought-after individual in the entire medical department. My peers, who snubbed me during my adolescence, now fought for a chance to have me for a study partner. They rapped on the door of my suite of rooms, attempted subtle bribes and invited me to family outings. For once, I had the power of rejecting one companion in favour of another.

I look back to the winter of 1881 and the succession of triumphs: my first public demonstration, concerning the breakdown of the red blood particles, followed by the first round of applause from the entire department, my first dinner at Professor Handley’s house and my first excursion to the opera with his daughter without a chaperone. My future father-in-law could find no fault with my behaviour towards Elizabeth.

I must confess I was never tempted to behave in any other fashion, even though Miss Handley herself kept testing my composure subtly and unobtrusively. At the time I attributed my lack of desire to violate the code of gentlemanlike demeanour to the fact that my father was a reverend. He taught us that certain desires ignite only after marriage. Disciplined young men, firm in their Christian faith, do not feed their wanton fancy. To repress one’s sinful urges is a commendable feat, but not to possess them at all is a blessing.

Still, it flattered me that a woman should expend so much time and money to look more appealing in my eyes. It is marvellous what discomforts women are willing to bear in order to make their waists appear narrower and their bosoms ampler. I expressed my appreciation of her efforts through terse compliments, which delighted her parents.

Gradually, I began outgrowing my malady. The symptoms did not vanish altogether, but they lessened considerably. This unexpected improvement in my condition prompted me to make a vow to God that I would devote my life to treating the ailments of the lungs.

Then the white-haired Welshman barged into my kingdom, and my wheezing attacks returned, with doubled intensity. When I was near him, I lacked for air. Griffin was stealing oxygen from me. As slender as he was, as few personal possessions as he owned, somehow he occupied most of the two-bedroom suite in the residence hall that we shared. Every corner bore the mark of his presence. Some invisible, elusive spirit reigned there, leaving practically no space for me.

Griffin’s bedroom served as his personal laboratory where he would continue his experiments into the middle of the night. His arsenal included an assortment of glass tubes in which he would heat and mix various chemicals. I knew better than to pry into the nature of his experiments, but I suspected it was the fumes seeping from under the closed door of his bedroom that triggered my coughing attacks.

Still, I had no grounds for complaint, as there was nothing criminal about Griffin’s behaviour. Who can fault a science student for diligence? If his work stirred my old illness, it was my private ordeal. Remains of pride forbade me to vocalise my growing discontent. Most of all I feared being accused of having a Salieri complex.

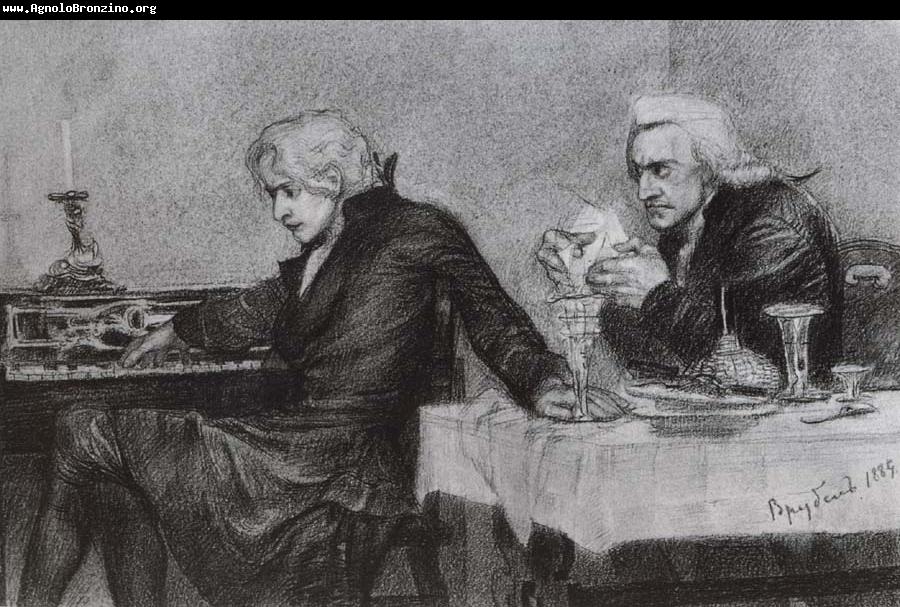

Mikhail A. Vrubel, Salieri and Mozart, 1885

|

There was nothing left for me to do except drive my anger deep into my inflamed chest. When the tightness in the lungs became unbearable, I would simply go outside or wander the corridors of the residence hall. Nobody ever found out how many nights I spent on the cushions in the lounge. And nobody found out about the tempest inside my head. It was not my crown that I missed, it was my freedom. I learned what it meant to be a spiritual captive of another human being.

I knew that now, when my fellow students knocked on our door, it was most likely for Griffin, not me. Rarely would he deign to come out of his sanctuary and greet them. Usually he would remain behind the closed door upon which they would throw furtive, longing glances. With the immediacy of small children they would elbow each other and whisper.

“He’s been there for hours. What’s he doing, toying with explosives?”

“I know: he’s building a time machine.”

“Stop reading so much Jules Verne. It will do your pretty little head no good.”

“Well, at least I’m reading.”

“I tell you, albinos are all evil. It’s a mark of the Devil.”

“Listen to you! Sounding like you’re straight from Oxford. Believing in the devil is no longer fashionable.”

“Well, if the Devil exists, Griffin is his incarnation.”

“Bah, you’re just envious!”

“I say, he’s dissecting rats.”

“Bosh! One doesn’t need to go to university for that.”

“This is no university. It’s glorified butchery.”

“Gentlemen, is it just my imagination, or does Griffin’s hair look a bit whiter than it was before? I didn’t think it was possible. And his skin! Did you see his skin? It’s translucent. You can see the veins and everything.”

“Here’s an idea. Why don’t you knock on his door and ask him?”

“Like hell I will! You knock first.”

“After you.”

“No, after you!”

Men of science do not hesitate to mock those they venerate the most.

Yes, they still consulted me on academic matters. I convinced myself that they were doing it out of habit, or duty, or, perhaps, pity.

And yes, I was still welcome at Professor Handley’s dinner table, but so was Griffin, although he did not take advantage of this privilege frequently. On those rare occasions when he joined us, Elizabeth would become noticeably distracted. She would study Griffin’s face, as deliberately and as blatantly as her upbringing allowed, while he remained oblivious to her presence. He spoke very little and ate even less.

Between courses he scribbled in his notebook with which he never parted. His colourless lips kept moving, whispering formulas. His garnet eyes would squint and widen, as if from flashes of light. In those moments he resembled a monk immersed in perpetual prayer. And Elizabeth would sigh and smile sadly. Apparently, the white-haired genius struck a chord that I never had. Not that it mattered to me. One more defeat made no difference.

Handley, delighted to now have two adopted sons, nurtured his own designs. One Friday afternoon, just before dismissing the seminar, he suggested before everyone that Griffin and I should collaborate on a study.

Science professors cannot boast about being the most tactful men in the world. This is no earth-shattering revelation. Handley was no exception to the rule.

“Every semester my students grip each other by the throats for a chance to partner with Samuel Kemp,” he said, beaming at his own ingenuity. “This time I decided to try a different approach. I will remove both Kemp and Griffin from the battle and assign them to each other. It would be presumptuous on my behalf to speak for the entire University College, but personally I am very anxious to see what miracles these two brilliant young men can concoct together.”

For a few seconds everyone in the hall ceased breathing and looked at Griffin, for he, apparently, had the final say.

“Is this a mandate?” he inquired, tapping his lips with the tip of his pencil.

“Not at all,” Handley reassured him hastily, “merely an unobtrusive proposal. Since you and Samuel Kemp already spend a considerable amount of time under the same roof, perhaps you would use this time more constructively, for the benefit of your respective careers.”

Griffin straightened out and clutched his notebook to his chest. “If this is a mere proposal, then I fear I must politely decline it, Professor. You see, I am not quite ready to share my work with anyone, even Samuel Kemp... with all due regard.”

There was no deliberate hostility in his voice. Still, his declaration solicited a number of stifled gasps from the audience. What? Samuel Kemp received his first outward rejection! Suddenly, everyone’s glances shifted to me.

My chest tightened. I felt a sudden need to unbutton my collar. The prospect of having a coughing attack in front of my fellow students petrified me. God be my witness, I tried not to be angry with Handley. Nor did I doubt his benevolence. The man sincerely believed his idea brilliant.

“Professor,” I mumbled, raising a sweaty, trembling hand. “I was about to present the same objection, but Mr. Griffin pre-empted me. I believe it is in everyone’s best interests that we work separately. Following his example, I will take no partner this semester. I would like to think that I have earned my autonomy.”

Handley looked perplexed, not heartbroken. “Who am I to argue with geniuses?”

He turned his back to us and began wiping the blackboard, letting everyone know that the class was dismissed.

* * *

Copyright © 2011 by Marina J. Neary