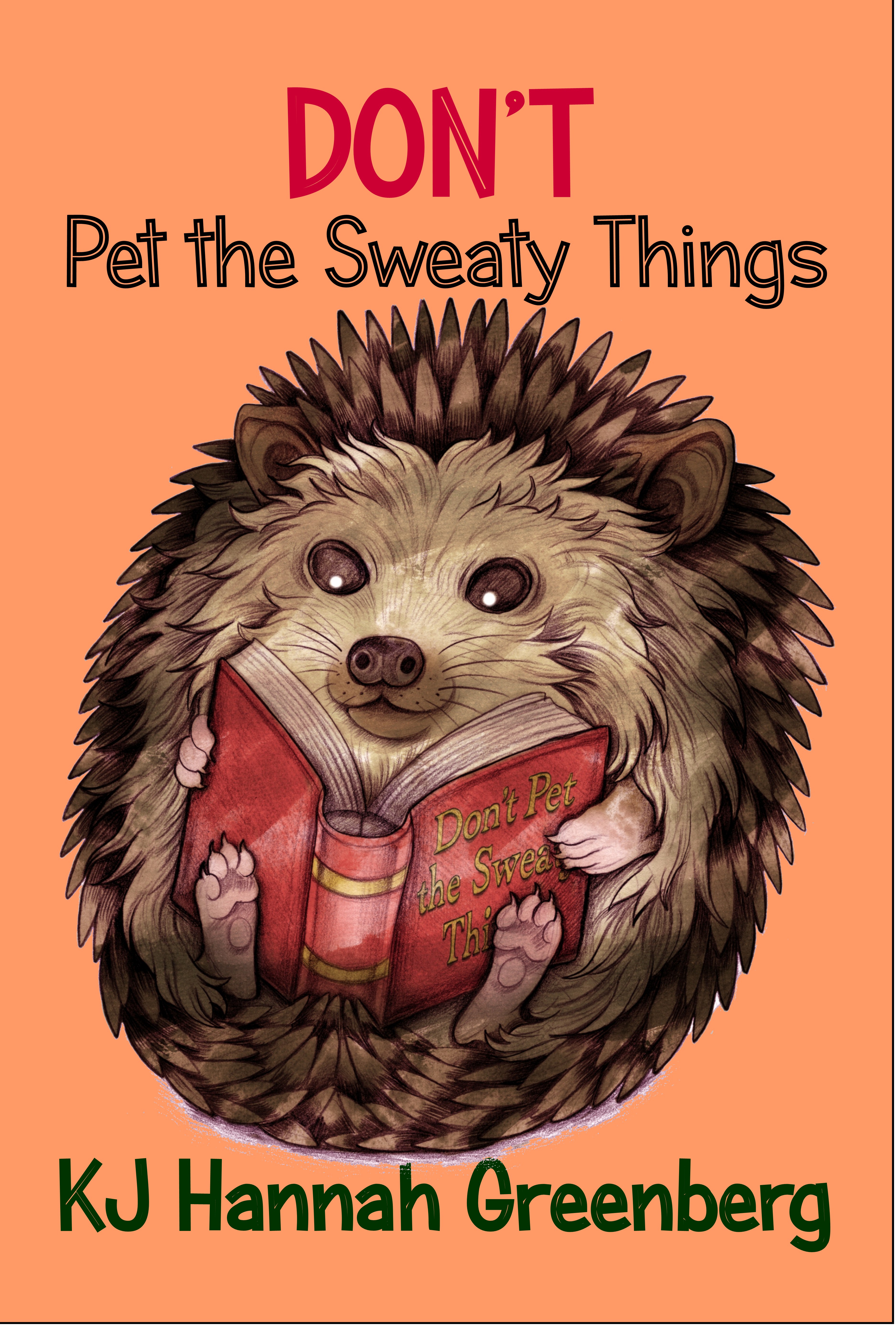

Channie Greenberg, Don’t Pet the Sweaty Things

reviewed by Don Webb

Don't Pet the Sweaty Things a.k.a. Channie Greenberg Publisher: Bards & Sages, 2012 Length: 200 pp. ASIN: B007P99848 |

But readers can relax; the language is part of the fun. This collection of short stories ranging from less than a hundred to several hundred words in length deals with the most mundane — or elemental, depending on your point of view — features of existence, such as family, neighbors, lovers, politicians, and sometimes unusual items in the news. To take a few examples:

The environment: In “Daisy Chains,” a mutated organism observes a forlorn lover’s mourning a futile love outside a partially melted-down nuclear power plant.

Politics: In “Kelev Liked to Suck the Marrow Best,” a jackal eats an NGO agent who has been killed by a sentry, a fate befitting foreigners who meddle in local politics and expose natives to invading barbarians.

Family: In “Maneuvering the Facts...” Alex the computer is assigned to a boring job but entertains himself by downloading porn. He is foiled by a virus, presumably his mother’s.

In “The Martian and the Potter...” an artist is harassed by her husband, who insists on a conventional style in ceramics.

In “Droving Away Unpleasantries,” a sheepherding family adjusts to technological advance moving at a science-fiction pace.

In “Nest Eggs and the Cryptids,” children benefit from an inheritance but object to their mother’s lizards, which have a habit of eating obnoxious neighbors.

Neighbors: In “Professional Responsibilities,” a psychiatrist finds a therapeutic respite in his pets, including a chimera.

In “Squamata’s Rumble,” a biker dude comes a-cropper while speeding.

And in “Inheritance of the Meek,” a woman notices but is not especially concerned by the sudden deaths of many important people, including those around her.

Lovers: In “To Pursue a Criminal,” a hotshot police airwoman is killed by her lover, who feels bored and outclassed.

And in “Simple Combinations,” a jilted lover commits mayhem in a chemistry lab but, in jail, is carved up by her murderous cellmate.

These everyday stories are transformed by language into a poetic experience. The vocabulary is by turns erudite and technical or “sidestep.” For example: “The hyperopic Erinaceinae watched the two-legged giant gambol” does not have to be understood literally. All the reader needs to know is that we’re looking at a girl from the viewpoint of a mutated animal. And from that perspective readers can see why the “two-legged giant” might despair of love.

The author’s experience in science writing can be seen in such passages as:

“Artemisia’s thoughts sifted back to forewings and hindwings. Biology had been a much better course. There had even been the week, after much ado was made about the essential qualities of nucleic acids, amino acids, sugars, lipids, and water, and about the dissimilarities between eukaryotic cells and prokaryotic cells, when the students had explored the differences between mitosis and meiosis.”

That passage is easy to follow as an image of Artemisia’s musings about Morris. And the subsequent explosion in the lab makes perfect sense in terms of chemistry.

Occasionally words come as a surprise, for example:

“busybodies who claimed either to understand local politics from afar, or who espoused that they represented the opinions of the total of humanity.”

One would not expect “espoused,” but it makes sense after a fashion. And it’s the sort of thing one gets used to while not “petting the sweaty things.”

Language is at its best when it draws the reader into the artist’s experience, But language can also serve other, almost contradictory purposes.

In the mid-17th century, Molière’s satirical play Les Femmes savantes won the day against an elite subculture that used language for its own sake. His objective was that of Louis XIV himself: to create a language to unify a modern nation being forged from a collection of medieval provinces.

But the culture of Préciosité that Molière derided was on to something. Famous phrases like le supplément du soleil (literally: “sun supplement,” i.e. a candle or, by extension, any artificial lighting) and l’ameublement de la bouche (literally: “mouth furniture,” i.e. teeth) illustrated a form of encryption that can come in handy today, when subversive thoughts and plans can be broadcast by mass media and yet may manage to sidestep their targets, be they family, lovers, neighbors or politicians.

Copyright © 2012 by Don Webb