The Man in the Mirror

and the Monster in the Middle

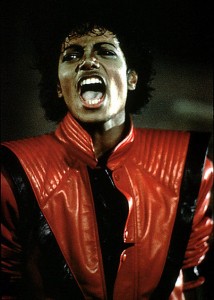

Michael Jackson’s Thriller

by Nathan Rosen

Director: John Landis Producers: George Folsey, Jr., Michael Jackson, John Landis Writers: John Landis, Michael Jackson Starring: Michael Jackson Co-Starring: Ola Ray Distributor: Epic Records and Vestron Music Video Released: December 2, 1983 |

By the end of his life, Michael Jackson had become a monster. He transformed himself over the course of decades from a handsome young man into a pallid homunculus, secluding himself from humanity like Frankenstein’s creation or the Phantom of the Opera. Many believe he even committed monstrous acts; although he was exonerated by the courts, rumors and speculation will surely persist for as long as he is remembered.

The sad truth, though, is that Michael Jackson’s decline should have come as no surprise. He spent his life unsure of who or what he was, never able to commit to being one thing or another, and we can see Jackson’s crisis of identity clearly in the artifact that marks the apex of his career: John Landis’s 14-minute short film Thriller, which was written by Jackson and Landis, and made its nationwide debut on MTV on December 2, 1983. As I examine Thriller I want to answer two questions in particular: Why did Jackson want to work in the horror genre, and why did he cast himself as the monster?

A lot has been said about Thriller in the years since its release, ranging from the scholarly to the banal to the downright ludicrous. For example, in 2004 Pastor Joe Schimmel of Good Fight Ministries devoted a segment of his ten-hour opus They Sold Their Souls for Rock n Roll (sic) to Thriller, arguing that its horror imagery, particularly the animated corpses, is proof that Jackson was a Crowleyan occultist in league with “the demonic spirit-world.”

Notions of that ilk aside, probably the best reasoned analysis of Thriller was written in 1986, a mere three years after the film’s release, by cultural critic Kobena Mercer. His article “Monster Metaphors: Notes on Michael Jackson’s Thriller” was published in volume 27, issue 1 of the journal Screen, and in it he proposes that Thriller presents Jackson as a figure perched on the boundary between two states: “Neither child nor man, not clearly either black or white and with an androgynous image that is neither masculine nor feminine.” Mercer also touches on the contrast between Jackson’s real-life status and the characters he plays, where he straddles the line between superstar and boy-next-door.

Mercer concludes that the film’s presentation of Jackson as a monster is a revelation of Jackson’s self-image, and even boldly suggests that the transformation sequence is “a metaphor for the aesthetic reconstruction of Michael Jackson’s face.” I believe Mercer, on the whole, was exactly right and very prescient in his conclusions about Jackson’s presentation and psychology, but I also believe that his article falls short because it lacks an examination of many of the horror tropes that Jackson and Landis appropriated.

Closer inspection reveals more support for Mercer’s thesis than I imagine he ever dreamed of, and we can see how the motif of liminality — existence between two defined states — permeates every moment of Thriller. We can then use principles of horror study to form theories about Jackson, and corroborate these theories with documented facts about Jackson’s personal life at the time.

I’d like to take a moment to briefly explain two concepts, both fundamental to the field of horror studies. The first is the “uncanny,” which encompasses everything that we can’t understand and that doesn’t fit into our frames of reference: death, decay, deformity — in short, everything that disturbs us and makes us uncomfortable.

The second, and more important to this analysis, is “liminality,” which as I’ve said refers to borders or boundaries. Horror is a liminal phenomenon because it relies on the incursion of the uncanny into normality, but liminality itself can also be uncanny. When we can’t easily define a thing, because it seems to exist as a combination or refutation of two mutually exclusive states, we become uneasy. As a result, many common horror tropes rely on liminality as their base.

(One final digression: In Thriller, Michael Jackson’s character is addressed as “Michael,” and Ola Ray’s character is never named. For the sake of clarity, I’ll use “Jackson” and “Ray” when referring to the performers, and “Michael” and “Ola” when referring to the characters they portray.)

Thriller begins with a disclaimer that the film does not reflect any belief in the supernatural on Michael Jackson’s part — a statement apparently ignored by Pastor Schimmel. Following that, the first thing we see is Michael and Ola out for a late-night drive in a convertible. He’s wearing a letterman’s jacket emblazoned with an “M,” and she’s dressed in a demure sweater and skirt ensemble. We can tell from their clothes and car that they are typical American teenagers in the 1950s — or, rather, in the fictionalized, idealized 1950s familiar to us from movies and television shows.

Already we’re seeing boundaries being blurred, because the stereotypical roles that Jackson and Ray are playing would, in authentic artifacts from that time, undoubtedly be filled by white people. They belong to a very specific social class that simply was not, on the whole, accessible to black Americans in the 1950s.

The car runs out of gas and putters to a halt, and Michael and Ola get out and walk. Michael turns to Ola, tells her that he likes her, and asks if she shares his feelings. She does, so he gives her his class ring, but then momentously confesses, “I’m not like other guys.”

This line positively drips with ambiguity and liminal significance, because of course he’s not: he’s Michael Jackson, superstar, with all that that entails. The viewing audience is expected to perceive his character (the wholesome ’50s teen) and at the same time recognize his real-life identity as possibly the most famous person on Earth. To drag all this into the spotlight with the line “I’m not like other guys” is downright daring, and almost too delicious to bear.

We soon learn the diegetic reason for Michael’s difference, though, when the full moon emerges from behind a cloud and Michael transforms into a hairy, fanged monster, courtesy of makeup effects by Rick Baker (who also created the werewolf transformation effects in Landis’s 1981 An American Werewolf in London).

Mercer, when he reaches this point in his analysis, wisely addresses the symbolism of werewolves as representing a notion of hypersexual, predatory masculinity, and contrasts this with the almost asexual presentation of Michael Jackson at this stage in his career. Oddly, though, Mercer seems to find only humor in the contrast between the bestial monster and Michael’s ’50s persona:

Michael-as-werewolf lets out a blood-curdling howl, but this is in hilarious counterpoint to the collegiate “M” on his jacket. What does it stand for? Michael? Monster? Macho Man? More like Mickey Mouse. The incongruity between the manifest signifier and the symbolic meaning of the Monster opens up a gap in the text, to be filled with laughter.

Apparently Mercer doesn’t recognize that this contrast, while it certainly can be funny, is already a familiar trope. We see it as far back as the 1957 Michael Landon vehicle I Was a Teenage Werewolf (which Mercer does mention elsewhere in his article), but also to varying degrees in all modern-day lycanthropy horror films, including the aforementioned American Werewolf as well as The Howling (1981), Full Moon High (1981), and Teen Wolf (1985). The last is notable because although it postdates Thriller, it was a box-office success and Mercer should have been aware of it at the time of his writing.

What Mercer also does not mention, in support of both his thesis and my own, is the nature of a lycanthrope as a liminal phenomenon. It is neither man nor beast, both civilized and wild. And indeed, we find still more liminality in the realization that, even if we are familiar with werewolves as a horror trope, upon closer inspection Michael does not appear to be a werewolf at all.

Look more closely at his yellow eyes with vertical, slitted pupils, and at the prominent whiskers protruding from his cheeks. These are features of cats, not of wolves. In the 45-minute documentary “The Making of Thriller,” which was distributed with the film on home video, Rick Baker describes the monster as a “cat-beast.” Baker also shows off his design paintings, and they do appear more catlike than the final version.

Of course, in her interview segment Ola Ray uses the word “werewolf,” so the ambiguity clearly existed even on the set of the production. Neither man nor beast, and neither wolf nor cat, the Michael monster is a new phenomenon, stranger and more liminal than anything we’ve seen before.

Ola flees and Michael pursues her through the woods, and suddenly the film undergoes a massive paradigm shift, cutting to the interior of a movie theater (the Palace Theatre in Los Angeles). Everything we had seen before, which in the absence of any clues to the contrary we had assumed to be the film’s internal reality, is revealed to be nothing but a film within a film. Sitting there in the audience are Michael and Ola, now dressed in modern styles. With this shift of perspective, the boundaries between film and reality and between performer and audience are utterly shattered.

Conflict is already present in this new reality, as Michael is enjoying the movie, but Ola is scared and wants to leave, and she does. Michael follows her out of the theater and into the night (Michael physically following or pursuing Ola seems to be another recurring theme in Thriller) and only now does he actually begin singing the title song, the film’s ostensible raison d’être.

He sings in the context of convincing her about the fun of horror and of being scared, and Ola’s broadening smile indicates that she’s warming to his opinions. Everything seems to be going well, and indeed everything seems normal and mundane, until their walk brings them past a cemetery and we find ourselves once again in the universe of horror.

As the sonorous, disembodied voice of Vincent Price recites an ominous rap, decomposing corpses claw their way out of their graves and begin to shuffle down the street. Mercer finds more humor in the unlikelihood of “a well-established white movie actor like Price delivering a ‘rap,’ a distinctly black urban cultural form,” but he also recognizes its significance as yet another indicator of how Jackson’s music crossed racial boundaries. Jackson performed in the context of mainstream, white, popular music, but incorporated stylistic techniques that were at the time limited to genres such as soul or rhythm and blues. If he could bridge the gaps in that manner, why shouldn’t Vincent Price be allowed to rap?

As for the zombies themselves, Mercer offers a very valid and perspicacious observation. He sees them as a contrast to the beastly, sexual transformation from earlier: “Unlike the werewolf the figure of the zombie, the undead corpse, does not represent sexuality so much as asexuality or anti-sexuality, suggesting the sense of neutral eroticism in Jackson’s style as dancer” (italics Mercer’s).

As he continues, he comes even closer to the argument I wish to make: “The living dead invoke an existential liminality which corresponds to both the sexual indeterminacy of Jackson’s dance and the somewhat morbid lifestyle that reportedly governs his offscreen existence.” This marks the only use of the word “liminality” in Mercer’s article, but it is enough to prove that he and I are in agreement. As zombies are liminal phenomena themselves, being neither alive nor dead, they serve as one more symbol in Thriller of Jackson’s own ambiguous self.

By the time Price’s rap ends, the zombies have surrounded Ola and Michael and are “closing in on every side,” to quote the song’s lyrics, and this is where the film takes its strangest turn. Ola looks at the zombies pressing in and turns to Michael in hopes of protection and reassurance, but he has become a zombie himself. But why? I don’t ask narratively; there’s no need for explanation in a horror movie. I want to know why Jackson and Landis made this decision.

Thriller was meant to be a showcase of Jackson as a leading man. He could have played the part of the pure hero (relegating the earlier monstrous transformation to mere fiction) and done battle with the zombies, driving them away and saving Ola’s life and virtue. Surely Jackson and Michael Peters, his co-choreographer, could have created a phenomenal dance routine around this concept, every bit as memorable as the one they did create. But they chose not to, and Jackson made himself a monster instead.

Not only does Michael join the zombies, but he leads them in elaborate choreography with himself as the apex of a V shape, echoing the form of his red leather jacket (created by Deborah Nadoolman, master costume designer and John Landis’s wife), which is now tattered and decayed. His control over them is indisputable. And yet, Michael can’t even seem to commit to this new state, as he reverts back to his normal self, clothes and all, whenever he begins to sing. We have no clues of perspective that might indicate an unreliable point of view, so we’re forced to assume that the transformation back and forth between zombie state and normality is happening just as we see it: yet another unstable, liminal condition.

Ola, understandably, flees. She runs to an abandoned house (actually the Sanders House in Los Angeles, built in 1887) as Michael and the other zombies give chase, and she barricades herself inside, but to no avail. The zombies come crashing through the door, and the windows, and even the floorboards, breaking the line between safe and unsafe spaces in a fundamental horror trope. She’s trapped a corner, and zombie-Michael comes closer and closer...

And then she wakes up. The house isn’t a decrepit ruin, but in perfect condition. Michael is standing over her as before, but only out of concern. He’s very much alive, and there are certainly no zombies in the house. Some portion of what we thought was reality was in fact a dream, but how much? If Michael and Ola really went to the movie, but the zombies were all in Ola’s dream, then how did they get to the house? For that matter, whose house is it?

We don’t know, and the uncertainty throws us off balance, but at the very least everything seems to be all right as Michael and Ola walk towards the door... until Michael turns back to the camera, revealing the same monstrous, yellow eyes he wore for his first transformation. Reality, dream and movie-within-a-movie collide in a perfect liminal uncertainty. To underscore the tension, the frame freezes, and we zoom in on Michael’s face as Vincent Price’s laughter echoes over the scene. Fade to black, and end.

So what did all this mean to Michael Jackson? We may find some answers in “The ‘Thriller’ Diaries” by Nancy Griffin, published in the July 2010 issue of Vanity Fair about a year after Jackson’s death. Griffin was on the set of Thriller covering the shoot for Life magazine when Landis decided he needed a “ticket girl” in the booth outside the Palace Theatre and cast her on the spot, giving her a perfect vantage point from which to watch the filming.

Griffin’s article describes Jackson’s upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness, under the thumb of his emotionally and physically abusive father Joe Jackson. At the time of Thriller, Jackson still lived awkwardly with his family — even after Katherine Jackson filed for divorce from Joe in 1982, Joe refused to move out of the house and instead moved into a bedroom down the hall.

Griffin quotes Jackson as saying, “I never was a horror fan. I was too scared.” And yet he watched horror movies, including An American Werewolf in London, perhaps in an attempt to conquer his own fear and assert his own identity against that of his father. Jehovah’s Witnesses are forbidden, or at least strongly discouraged, from watching horror movies, so doing so would have been an act of rebellion for young Michael Jackson.

This certainly explains the attraction of the genre, but why did Jackson insist on being the monster in his own video, rather than the hero? John Landis is quoted (in Griffin’s article) as saying that Jackson “wanted to be turned into a monster, just for fun.” I believe he wanted to play a monster for two reasons. First, the monster in a horror setting always has a position of power, at least for a portion of the story. Jackson felt oppressed and powerless against his father, and even to a degree trapped by his own fame, so the appeal of assuming this powerful role is self-evident.

Second, and I think more unique to Jackson, is that he felt like something of a monster himself, being an outsider even among his own family. According to Griffin, Michael had furnished his bedroom in the Jackson home with five fully dressed female mannequins, which he called his “friends,” and regularly brought Muscles, his pet eight-foot boa constrictor, to the Thriller set as a sort of living security blanket. He was different from others, and he knew it, and everyone around him knew it. He was such a liminal figure in reality that he would surely sympathize with any fictional monster in a similar condition.

Michael Jackson’s career never again reached the heights that it did with Thriller, and the remaining half of his life was troubled and strange. But one thing remains certain: For one brief, shining moment, the lifelong outsider Michael was able to show the world not the monster they thought they already saw, but the monster he wanted them to see.

Copyright © 2012 by Nathan Rosen

Proceed to The Critics’ Corner...