Take Just One

by Charles D. Tarlton

Someone called him the Picasso of the Homeless. They say he fought poverty, disease, violence, hunger, and fear with the “wild beauty” of his art.

|

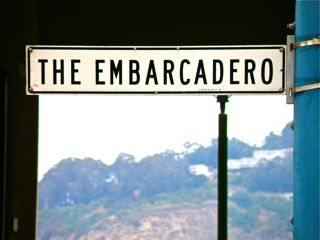

Up and down the Embarcadero, we were all familiar with those brilliant little gull-bone spheres, the maddening mother-of-pearl Rubiks, all perfectly right-angled, and who could forget the chalked Flemish-Baroque miniatures that would appear without notice in the most obscure stretches of sidewalk, under a bench, on an unused door.

He lit up that raggedy-ass world of outdoors-all-night sleepers and hungry grubbers. He showed himself by his works, and then, as quickly, he disappeared.

|

The Daily-Sun-Standard assigned me to the story, and I started out by hanging around Starbucks near the Ferry building in the mornings and then making my way slowly up to Fisherman’s Wharf. I talked to everyone: security guards, construction workers, cooks outside for a smoke, tourists, ad-men and lawyers on their way to work, secretaries on their way home.

Here’s what I finally came up with. He had been discharged from the Marines after serving in Iraq but suffered from PTSD. He lost some of his medical benefits. Someone said he took Art courses at the Recreation Center, but dropped out. Somebody else told me he had family down in Redwood City, but they disavowed his current “lifestyle,” as an aunt had put it, and his crazy talk. But everyone agreed that one day he just disappeared.

One day he sat in front of the big Peruvian restaurant with a sign so compelling they all wondered why no one else had thought of it before:

Hey!! I almost died for you

The least you can do

Give me a buck or two

Semper fi, suckers

And the next day, he was gone.

|

He was not long in becoming an urban legend and the first stories about the art began to circulate. Someone said they’d seen him after dark down under the Bay Bridge stirring away at something with a stick. When they approached, he put it all away and pretended to be sleeping.

Afterwards, that exact thing — or things very similar — happened with a certain regularity. He’d frequently been seen absorbed in some kind of secretive work with his hands, and once there was a spot of spilled red paint in the shape of a monks’ hood where he had been sitting.

He took to pushing a grocery cart around, and it was full of weird things like a sledgehammer, some sticks of wood, fish nets, balloons in bright colors, and a soldering iron.

When he talked at all, it was about things like the Giants and the stock market, but if anyone brought up the issue of his comings and goings after dark, he would clam up. So it’s easy to understand how this mystique grew up around him. My bosses wanted something more specific, his real name — by this time street people called him “Dr. Zwingli,” though I don’t know why — where he actually came from, and what, if anything, his strange behavior meant.

I tried once to interview him, but all he would say were things like “Yo no conozco a ningún verdades reales.” I tried to say something back in my little bit of Spanish, like “Who are you?” but it came out “How are you?” and he just looked at me and said, “Dudo que lo entenderías.” So, I gave up the direct approach.

I published one little story that appeared somewhere deep inside the Sunday edition. I just wrote that he was the mystery man of the Embarcadero, and no one knew who he was.

That was about the time people started receiving the strange little artifacts he’d made. He’d leave them in a taxi while the driver was gone for coffee, or he’d just hand them to tourists and Mexican workers at the Slanted Door. It got around that he had been making these very postmodern objets d’art, and his fame spread quickly in that art-hungry environment.

|

Your more assertive types started making specific requests, but he refused to take orders directly, and suddenly this little old homeless woman became his agent. You could talk to her, tell her what you were feeling, how your life was going, what made you happy, and then in a few days she’d come up to you and give you this little package with a poem scratched on a rock inside or an empty peanut butter jar filled with cloudy salt water and blue and green sea glass.

This was about the time he dropped out of sight altogether, although the old woman still talked to people, and the pretty little enigmatic things kept appearing. As time went by, more and more people were making requests; there would occasionally be a crowd of supplicants around the woman. She eventually had to recruit help, and then there were three, sometimes even four women taking orders.

They brought a big colorful wooden trunk down to the dock and put it behind Hornblower’s Dinner Cruises. People could come there in the morning, sort through the art work, and take the one that best fulfilled their expectations. There was a handmade sign that said:

|

I don’t go down to the piers anymore. My beat was changed to cover commercial real estate, but I still hear sometimes about the “Picasso.” He’s become something of a myth now, I think; no one knows him or really claims to have known him, for that matter. I heard someone in the coffee shop in my new building say something about how there was a genius who started a whole new school of modern art in San Francisco, and that he had been a homeless man on the Embarcadero to begin with.

Text and photographs copyright © 2013 by Charles D. Tarlton