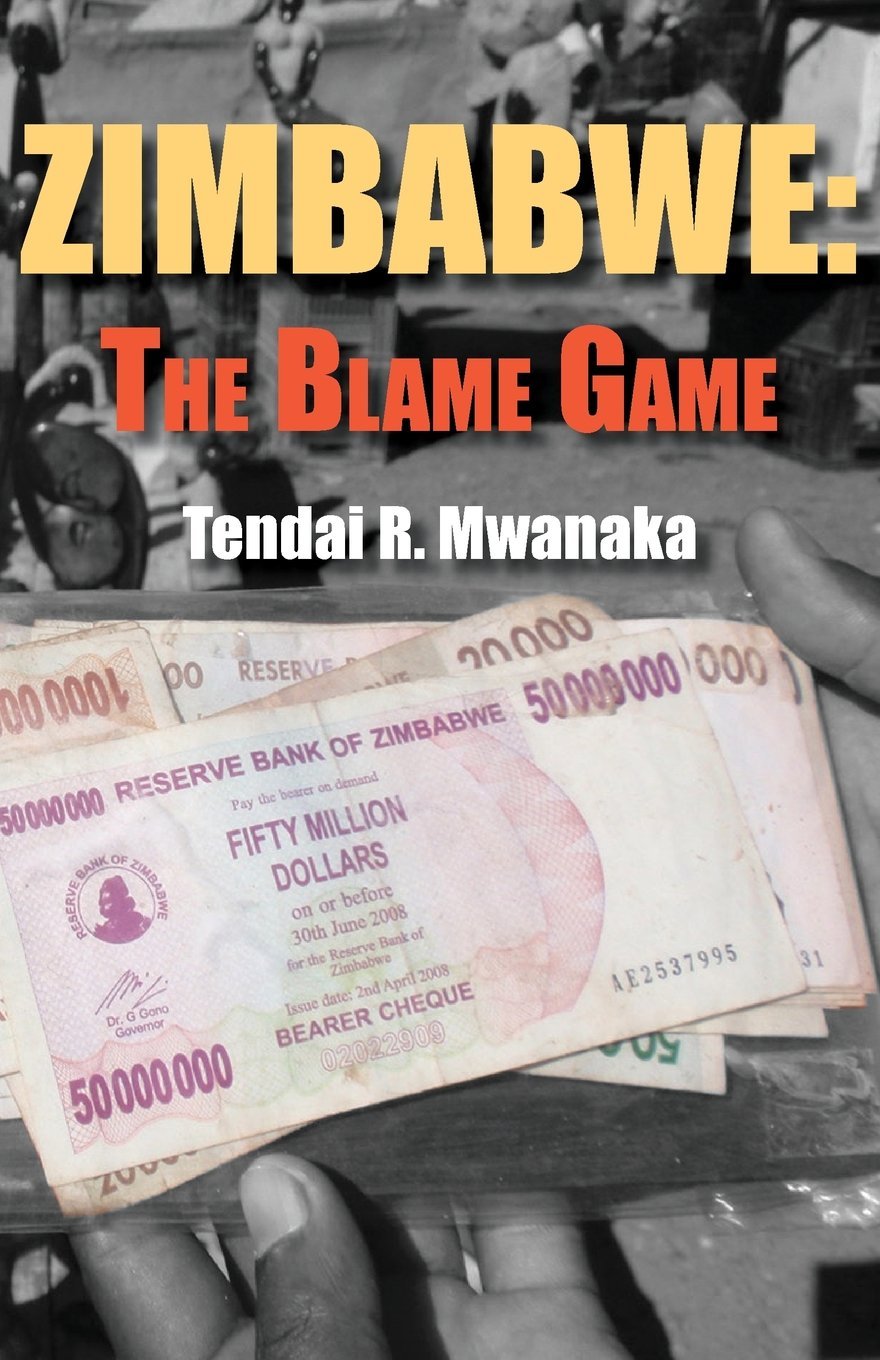

Tendai R. Mwanaka, Zimbabwe: the Blame Game

excerpt

Zimbabwe: the Blame Game Publisher: Langaa RPCIG Length: 222 pp. ISBN: 9789956728916 Interview: kubatana.net Sample: Google Books |

Children fashion out whimsicalities like “what ifs?” to deal with their existential dilemmas, and it’s two kinds of people who fix us to the earth: the indefatigable and the drawn-off. It’s the children who fix us to a place. We are unlike children so we can’t fix ourselves to a place. We are always trying to figure out our resulting identity, as a people in exile, wherever we are. To have a sense of belonging to this largest caste in the world we need the natives to exclude us and make us feel unwelcome in their countries. We have to use these imagined natives to wedge ourselves into this gap as exiles.

This piece plays on the collapsed gap between the narrative and the visual, a narrative of a life like or very close to mine. It is subjective. I am writing this with a stick on the road..., a farewell to my mother land. It is for those who dwell in dope-filled dreams of exile, imagining it to be the freedom’s door. I am at the service of those who suffer from history, and humanity always creates these people. The country of our infancy dreams is now an occupied country. It is difficult to talk about the mist still rising from this land we have forgotten to hate.

We leave our country because we wanted to leave, and the second reason why we leave our countries could be a corollary of the reason why we had left it, in the first place. It’s because of the situation in our mother country that has forced us to leave. Our life in our mother country was a miniature living hell. For both reasons of leaving; it is like a tot in the mother’s womb. We leave our mother’s womb because we want to leave, or because our mothers want us to leave and have forced us to leave. Cutting the umbilical cord when the child is born is separation in the physical sense. It’s the first cutting out of the connection between mother and child.

We can also decide to cut any connection we have had with the country of our birth. We do not want to know; what’s been happening there anymore, because maybe, we are busy ingratiating ourselves with our new country. Maybe we do not want to think of the painful situation we have left behind.

To stay in a foreign land is not to really belong, yet a sense of belonging grows, season by season, year by year. Staying in South Africa for me has been as if I was trapped in a car, travelling in a land I had never seen before. A land I could not touch, but I was touched by the land. On this journey, I have been totally alone and my interactions with the other people could rarely be categorized as human.

Maybe one has decided to keep some kind of invisible connection with his or her country. This connectivity can be thick and thin. It is fragile when it is constructed from memories or feelings of an absent mother or a lost mother. The memories will be an invisible web that ensnares our feelings. They are captured by a single thread which reels in the images, of the old country, or that of the mother’s body and all that it offered. It is thick when it is coloured by guilty; a sense of duty, or evil blind love for the mother’s country. Such would be the love that has outlived all our sorrows. The word “mother’s body” wills and bodes its own remnant to detach us from neural bliss. When it is like this it leaves a solid shadow on our psyche.

I want to think there are not a lot of countries in this world where there are no Zimbabweans in exile. The description of a wondering Jew suite us to a tee now, and the description embodies our wandering away. Mother’s in Zimbabwe now tended their hands, keen and call for their children spread all over the world. There is no sound: only silence in the whole country. The children have left their nests; the children have left their mother’s bodies. The grief of a whole country, mourning; the dead, the tortured and the lost, it’s not easy to talk about this.

Like many purblind young people, I decided to leave my country pushed by the belief that the grass was greener the other side. As I have said, I am now committed to exile, negotiating the position of refusal and acceptance of my destiny. I have understood how difficult it was to tend a land so far away from home, with so few means and know-how. I will husband this foreign land. I will stand on the streets, with throng upon throng of other unskilled labourers. I will hare my soul on these streets lamenting, and the tilling that goes on without me? In backyard cottages, shack towns, underground railways, I will lie low with my new life, wife, and children like the cactus in the sand. I will learn new customs and languages with the police sirens for dreams. With nowhere else to go, misery is when I know I can’t run away from where I am because there is nowhere else to run to. I can’t go back. I can’t go further. I am stuck here, for better for worse.

This is what we have to deal with once we leave our countries or our mother’s bodies at birth. For us to negotiate ourselves through a world that is outside of our mother’s bodies, we have to learn the language of use outside our mother’s bodies. Learning the native’s language in a land of exile equals a young child learning his first language for him or her to be able to communicate with the world outside mother’s body. The more the language is difficult and complex- the more they are many languages to learn- the more difficult and confusing the situation would be. Words (the language) become mother’s body. We are formed through discourse and words are the oil that lubricates this discourse. It is also a sea of shifting valences. They are no easy interpretive mechanisms that mediate or contextualise how subjectivity forms throughout this discourse.

It reminds me of John 1 vs.1, in the Bible. ”In the beginning there was word and the word was with God, and the word was God.” So it means; we are all after-word(s). We are after-mother’s presence. Mother is now the word, tongue, language, and the body. Separation from the mother’s body, separation from our mother country, languages, and customs is the beginning of exile. At birth we start the exile so to our knowledge we have always been in exile. We are narrators, we have a story to tell, and we are the story. From our first day on the earth, we negotiate what in the past we had lost. We call out to the lost one (mother’s body) to find the lost one (ourselves). That’s the pleasure of our lives, and of life in exile. To replace mother’s body, gender, and sexuality we exchange this with gender, sexuality and body of words; making a mother out of words. Maybe that’s why it wrecks some very bad feelings and emotions when someone insults one’s mothers’ body.

I have now been in exile for over two years. It has been so painful, but the pain can be blunted by dreaming of the past time and space in which fragments of memories can be made whole. I go for the memories like a hungry wolf going for blood. Like the wolf, it’s not uncommon to feel a shift of identity, and its fine to talk to my inside organs. It’s alright to try to figure out if they still understand me, but my body has no place of its own in my new country. It seems; my body has been consuming me. I don’t find enough blood or flesh in these memories but fragments of faded memories and, more dancing shadows the more I have stayed away from home. There is nothing more that must be wasted. I would have to cherish my memories and keep my blade near my centre for the sake of memory! Home now is a place in my heart and memories. The childhood home has become immemorial and recollected time. Memory and imaginations shapes it. There is a fine line that divides memories and imaginations, and in my dreams, it is so beautiful to drift and float in between.

But, as you stay a lot longer in exiled land you develop exile gaps with your mother country. You become like a fish that has been grounded on the beach. Beyond happiness or joy here, this country has simply wiped you. You are now a whistle far from yourself. It is so artificial. It would seem like you were not even there when the country plucked you out. Now this country is too huge for you to hold a memory of it, but it holds you. All that you have is misery, welcome into the real land of exile!

Exile is when your father and mother have become strangers to you. Exile is when strangers in your adopted land want to shun you because of your poverty but you haven’t been that happy, in many a moon. You don’t feel you belong anymore to any time, place or space. Recollection of memories and the preserved past history inside you do not bridge you to any particular time, especially when your history has been a painful one, and especially when the line that connects you to your mother’s country is now a thin one.

There are no parallel lines, convergent or divergent lines with your past. You live in between these winding lines, in spaces of differing memories that decreases with time, distance, culture and values. Your disturbed wandering and tainted mind grapples and grasps for memories, like shadows disappearing and reappearing on the walls of your mind. The touch that once connected you to your mother; you know even if you were to develop that touch again, it would never make you see your mother again in your memories. You know it’s enough with this history because this history would simply bind you to a non place, leaving you with nothing. You also know that if you continue being fixed, or fixated with your history, it would asphyxiate you. You have to leave all that and start anew and that’s all that’s left for you to do. The past now equates to a vanished history for you.

You can’t wait for this to be over: a stage, that’s what you call it. When this happens, it indicates that historic memory has gone and this generates multitudes of other long term problems: of rotting love, broken dreams, and hatred of the mother’s body.

Copyright © 2013 by Tendai R. Mwanaka