The Devil in Blues, Ragtime and Jazz

by Garin G. Webb

| Bibliography and References |

Part 3: The Devil’s Box; Ragtime

The guitar was the instrument of choice for the early blues musician. Its light weight was ideal for traveling and its relatively low purchase and upkeep costs kept it within the financial realm of even those of lower incomes.

However, in some African-American communities, it was esteemed at the level of the fiddle. As the fiddle had long been associated with the legend of the musician selling his soul to the devil, so too was this new instrument in turn-of-the-century Southern black America. Like the fiddle, it carried with it sexual connotations. Alan Lomax describes it:

The guitar is butted against the hips... and handled in a masturbatory way. Meanwhile, the strings are choked down close to the sound hole, and plucked, stroked, frailed as if female erotic parts were being played with, while the instrument itself emits orgiastic-like sounds.

Lomax could be criticized for stretching the metaphor a bit, but it is undeniable that the blues were roundly condemned for lascivious song content. The guitar, then, “becomes a synecdoche for all of the worldly, nocturnal, pleasure-centered activities that transpire in and around the Southern jook joint: dancing, drinking, smoking, cursing, fighting, and fornication.”17

“A box,” he gasped, while my mother stood frozen. “A guitar! One of the devil’s playthings. Take it away. Take it away, I tell you. Get it out of your hands. Whatever possessed you to bring a sinful thing like that into our Christian home? Take it back where it came from. You hear? Get!” I was stunned. The words dim and far away like words spoken in a dream. A devil’s plaything. I wanted to dispute the charge, but I knew that argument would mean nothing. My father’s mind was fixed. Brought up to regard guitars and other stringed instruments as devices of Satan, he could scarcely believe that a son of his could have the audacity to bring one of them into his house.18

Imagery was also used to promote blues recordings and concerts. The image below is from an advert for a new Ma Rainey record in the January, 1926 edition of the Chicago Defender.

Lording above a frightened woman is the depiction of a mysterious figure resembling the all-familiar Death character. The illustrators even went out of their way to exploit the blues-devil legend by printing “The Blues” across the front of the robed figure. With hand outstretched above the head of the woman, the ominous figure appears to be placing control via fear, like a marionette, over the female subject.

While not overtly racist, it might be noted that the damsel in distress does resemble a caucasian woman. This may have been calculated to appeal to whites seeking the allure of “exotic” black music.

Aside from the racial connotations that the imagery may or may not impart, the devil can be found lurking deep in the lyrics Ma Rainey sings (printed on the advert).

Play “Slave to the Blues”

“If I could break this chain and let my heart go free. But it’s too late now — The blues has made a slave of me.”

Contextual etymology of the words “slave” and “blues” is important to understanding the true devil of which Ma Rainey and blues musicians sing. “Blues” is a word that has shared several meanings in white and black societies throughout the years. In the 1700’s it was referred to as “the blue devils” when describing the hallucinations of alcohol withdrawal in white society.

By the early 1800’s it simply meant “drunk.” In black society, early blues music featured a dance called “the slow drag.” This involved dancing very closely to one’s partner, dripping with the sex of pelvic gyrations. This dance was also referred to as “the blues.”

Blues musicians were singing about an existence that traced its roots to what is essentially a one-way Faustian bargain, where the lives of their ancestors were forced into servitude without the promise of riches or, at the very least, a dignified existence. The “Blues” therefore represents the very conditions set forth by white Europeans.

Blues was born out of African-American song genres that span the gamut from the mundaneness of existence in work songs to the heavenly salvation of the spiritual. Each of the aforementioned genres share in common an expression of circumstances past and present.

The link with drunkenness should not be surprising, as it was a way of dealing with a life of oppression and second-class citizenship. To medicate oneself with drink; to get lost in the dance of the slow drag; to seek the soothing words of blues ballads that you aren’t alone in your present agony of existence, that was what Ma Rainey was referring to. The blues represents the “evil” condition that the white man has thrust upon the black. The white man is, therefore, the devil.

Ragtime Songs

As pianos and player pianos became more widely available and affordable for middle-class households, the sale of ragtime sheet music began to increase dramatically. In the years 1897-1919 there were 1,005 instrumental ragtime works published.

The peak came in 1899, when a glut of 124 published works reached the shelves of the music stores. Surely this was the result of publishers trying to capitalize on the growing ragtime fad. Conversely, in 1919 there were a scant seven instrumental rags published, a sure sign that the fad had run its course.

Further evidence of ragtime’s popularity were the emergence of Ragtime schools and ragtime instruction manuals in the late 1890’s. Ben Harney’s manual, Ragtime Instructor, was snatched up by hopeful amateurs seeking to be a part of this growing national phenomenon. Ragtime schools began to open their doors with the enticement, “Learn to play ragtime and be popular.”19

Ragtime’s African-American genealogy was well known by the time of its meteoric popular rise in America and in Europe. Fearful of what many saw as the dangerous influence of blacks on American society, a 1913 letter to the editor of the Paris edition of the New York Herald questioned, “Can it be said that America is falling prey to the collective soul of the negro through the influence of what is popularly known as ‘rag time’ music?”

Such warnings are weighted with the fear of the loss of racial and cultural homogeneity. The writer mentions further, that if America is in fact embracing the soul of the Negro that “it should definitely be pointed out and extreme measures taken to inhibit the influence and avert the increasing danger — if it has not already gone too far.”

Finally the author indicts the “Negro” by implying a lack of sophistication in music and a “primitive” moral nature: “The American ‘rag time’ evolved music is symbolic of the primitive morality and perceptible moral limitations of the negro type. With the latter sexual restraint is almost unknown, and the widest latitude of moral uncertainty is conceded.”20

Vitriol such as this letter might seem to be the aberration of one racist individual. However laden with racism as it was, it was given credence and viewed as fodder for musical debate with its publication in the music journal The Musical Courier.

While most white Americans were largely ignorant of or indifferent to African-American life and culture, ragtime’s black heritage was common knowledge. As Americans embraced ragtime, America’s moral standard bearers viewed themselves in a battle for national purity of race and the health of the moral fabric.

References to moral decay became part of the lexicon in ragtime criticism. With this in mind, the weapons of destructive propaganda were deployed in attempts at cultural branding. “In Christian homes, where purity and morals are stressed, ragtime should find no resting place. Avaunt the ragtime rot! Let us purge America and the Divine Art of Music from this polluting nuisance.”21

“Purging” ragtime from Christian homes was a way of stripping godly associations from the music and indirectly from African-Americans. Canon Newboldt, of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, put it bluntly: “Would indecent dances suggestive of evil and destructive of modesty disgrace our civilization for a moment if professed Christians were to say: I will not allow my daughter to turn into Salome?”

In a 1913 defense of Newboldt’s denunciation, the New York Times would further add legitimacy to the ragtime fear. The editorial says “that decent people in and out of the church are beginning to be alarmed at the crude and vulgar music and loose conduct accompanying it with dances defying all propriety. That this “example should be followed in all of the churches of England and the United States. We are drifting toward a peril and the drift must be checked.”22

The New York Times, therefore, associates religious virtue with shunning ragtime music. Here again, the African-American is associated with evil. If the critics and moralists are warning of the danger of listening or even dancing to ragtime, one can only wonder what the remedies are for those that perform the music, let alone of the ethnic group that created it.

In his article, Leonard reveals that those who leveled rhetoric against ragtime were not “simply the arch-conservatives or reactionaries troubled by ragtime but more reasonable men [...] who looked to religion for guidance when confronted by the fearful specter of degeneracy.”23

However, the author withholds any analysis that these criticisms were not just directed at ragtime but at African-Americans by association.

White perceptions of blacks paralleled the stereotypical imagery labeled on ragtime. Many of these perceptions involved the analog to drink or disease. Leo Oehmler warns that “a person inoculated with the ragtime-fever is like one addicted to strong drink.”24

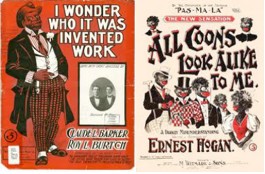

Here drunkenness is a byproduct of listening to the music. By using terminology such as “inoculated,” “addicted” and “fever,” the author fuses the clinical terminology of medicine with the music. Below is an example of a caricature of a seemingly “intoxicated” African-American. These caricatures adorned many faceplates of ragtime song and piano collections as seen in the illustrations below.

Play “All Coons Look Alike to Me”

Reactions and characterizations of these sorts were made against the backdrop of a country enamored with the pseudo-science of phrenology, eugenics, and a growing fascination with primitivism. As early as 1906, Paris began embracing primitive sculpture. This style would soon find its way into paintings and travel across the Atlantic where Americans would begin to embrace it during the jazz age of the 1920’s and the swing era of the 1930’s.25

Charles B. Davenport’s treatise on eugenics became a popular manifesto in the early years of the 20th century for those countries and communities seeking to “purify” and strengthen their race. Governments began to implement policies from birth control to euthanasia, with many respectable institutions and individuals granting organizational and financial support.

Those on the moral crusade to clean up the music of the youth, no doubt, took to Davenport’s words that “we have become so used to crime, disease and degeneracy that we take them as necessary evils” and “that they were so in the world’s ignorance is granted; that they must remain so is denied”26 gave moralists like Canon Newboldt intellectual cover to inveigh against these black music genres.

Americans had been dancing the waltz, schottische, quadrille, and the polka since the nation’s founding. These dances featured their own distinctive patterned rhythms, like the three-four meter characteristic of the waltz. While these dances all had their distinctive patterns, they were not as overt and percussive as in ragtime and jazz, which were radical musics to most white Americans. The syncopated and percussive nature of ragtime and jazz were the vestiges of the importance of rhythm in African music.

As if attempting to diagnose the music of the new generation, an unnamed doctor of neuropathy stated in a 1926 edition of Literary Digest:

The waltz of today fails to satisfy. Why? Simply because the nerves of the present generation are in such a state that they are soon bored by silence [...] jazz is rhythmic in the sense that a motor is rhythmic. It is all very well and good to talk about cross rhythms and syncopations in jazz, but these only serve to accentuate the absolute, unchanging regularity of the beat [...] Jazz devotees resent any irregularities of beat.27

Musicians like Daniel Gregory Mason took umbrage with jazz’s insistent beat: “If I am so dull that I cannot recognize a rhythm unless it kicks me in the solar plexus at every other beat, my favorite music will be jazz.”28

Not since the days of the Civil War had the country seen such a cultural shift. For the first time, on a mass scale, white Americans were consuming entertainment that came directly out of black culture. The intensity of the criticisms, images, and outright hatred for these genres was born out of fear of the “other”: people of color. This was caused by several factors having to do with migration, technology, and transportation.

As African-Americans fled the oppression of Jim Crow in the South, they brought the blues, ragtime, and jazz into the urban environment and, hence, to a broader and more diverse audience. As recording technology improved, more and more Americans were able to play these musics in their homes. And, finally, as transportation became more readily available and cheaper, what were once regional musical influences began to spread and homogenize the culture.

Given the freedom to move and the allure of work in manufacturing, steel mills, and the service-sector jobs of the North, blacks made their way into the neighborhoods of cities like Chicago, Cincinnati, Philadelphia and New York. Many whites now found that they were not only having to share the city with these new residents but that their music was quickly beginning to inundate the record store shelves, music boxes, and radio waves. Some compared the intoxicating effects of ragtime to that of alcohol in an obvious attempt to instill fear into the public.

Ragtime was a musical supernova that burned brightly in American popular musical culture from roughly 1895 to 1920. Its popularity and the allure of its infectious rhythms fused their way into the musical underpinnings of other genres of the 20th century, namely jazz. Ragtime entered American culture through traveling minstrel shows, vaudeville acts, piano players, bands and the sale of sheet music. By the early 1900’s ragtime had become a national obsession.

This rapidly expanding phenomenon also found its way into movie theaters, vaudeville shows, saloons, restaurants, nightclubs, the infamous speakeasy, and even into composers of art music. Charles Ives utilized these syncopated rhythms in many of his works from his most active periods from 1902-1920. Once the music traveled across the Atlantic it not only found its way into the casual public establishments but into the scores of prominent composers like Eric Satie, Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, and Antonin Dvořák.

Copyright © 2013 by Garin G. Webb