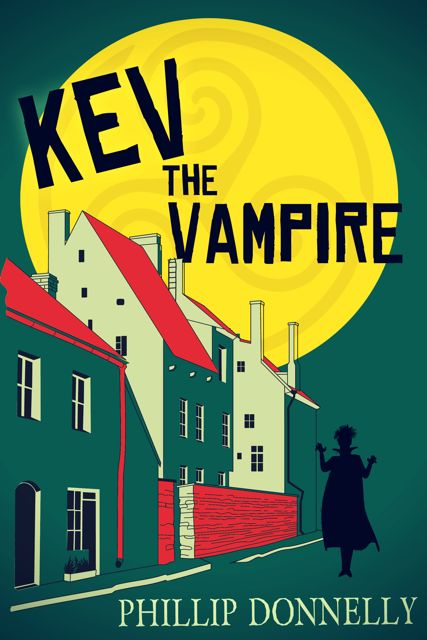

Phillip Donnelly, Kev the Vampire

excerpt

Kev the Vampire Publisher: Rebel ePublishers, 2014 Length: 394 pp. ISBN: 0692329161; 978-1311886156 |

Synopsis

‘The blood is the life! The blood is the life!’ is all a mysterious bullied teenage dropout, Patient K, will say.

The story is told by the vampire’s Freudian psychiatrist, in his ‘Notes on a Case of Obsessional Neurosis’. The deeper the psychiatrist digs, the more obsessed he becomes. Will the plot will consume the narrator, as the skeletons from Kev’s life threaten the doctor’s own world? Can his psychiatrist save Kev from his delusions or will the Dublin underworld consume them both?

The psychiatrist quotes from a variety of sources, so the epistolary style varies from literary to guttural, as he pieces together the story of K’s life: his gruesome school days at the Holy Bleeding Pelican; his drug-induced visions; his wars with social welfare zombies, estate agents, priests, the CIA, and his office supervisor. He learns about Kev’s romantic misadventures as a dishwasher in Bavaria, a speed dater in the Wisterna Club, and his doomed advances towards an air-hostess.

Kev the Vampire is primarily a psychological novel, but its quixotic hero means farce is never far away. More of a satire on vampire novels than a true vampire novel, the novel explores the themes of obsession, madness and violence.

“I sometimes think we must all be mad and that we shall wake to sanity” — Bram Stoker, Dracula)

Chapter 1

The Blood is the Life

“’The blood is the life! The blood is the life! Salvia divinorum!’ That’s all he ever says, Doctor.”

“Sage of the seers. Fascinating.”

“Infuriating, more like. I’ve just had sixteen hours of it. My head’s killing me! How much longer are we going to keep him under round-the-clock surveillance? My nurses never stop complaining about having to watch him day and night. Three of them have just called in sick. We’re short staffed, and Doctor Grá says-”

“Dr Grá is not his physician, Sister Driscall. I am.”

“Yes, Doctor. I’m sorry. It’s been a long shift. Has he ever said anything else to you? You’re spending a lot of time with him, I’ve noticed.”

“That’s all he’s ever said to anyone. That’s what he said when they found him, shivering and nearing death, deep in a forest in Bavaria. Hour after hour, I’ve stayed with him in my office, while he repeats his mantra, ‘The blood is the life! The blood is the life! Salvia divinorum.”

I stood in front of him. His gaunt, hollow eyes didn’t even see me. I must admit that, in spite of all my scientific training, I felt haunted by those green eyes of his - so demonic and twisted. It unnerved me to see them stare through me and beyond me, into who-knows-what world.

“My course is clear, Sister Driscall. I will explore his world and rescue him from it. I will bring him back to my world, back to the real world.”

“Can I speak my mind, Doctor?”

“Always.”

“What about all your other patients? I’m waiting on you to OK at least a dozen prescriptions. The depressives need their Benzedrine, the manics need their sedatives, and the schizophrenics need their Haldol. You can’t spend all your time talking to this delusional. He’s a hopeless case.”

“There’s no such thing as a hopeless case, Sister Driscall. No such thing! Every patient can be cured.”

I sent the nurse away. I needed to be alone with K. I walked around him, so tightly bound in his wheelchair that his body couldn’t move, but he twisted his head to allow his eyes to follow me.

“Do you know the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst, Patient K?” I asked him. He struggled in his chair but said nothing. “A psychoanalyst is part medic, and part detective. A normal psychiatrist is merely a dispenser of pills, an apothecary of the mind. I am no pill pusher.”

“Salvia divinorum!” he barked.

I sat in front of my curious skeletal case. I didn’t drug him; I listened to him. I pondered what lay behind his dementia. Some are born mad, some become mad, and some have madness thrust upon them. First, I would find the cause, then I would find the cure. “What has left your wits so addled, young K? Your reasoning so disturbed and disturbing? From whence does this madness come?” I said aloud.

“Blood. Life. Blood,” he rasped, over and over.

I sat behind my desk and opened my leather-bound notebook. In the centre of a clean A4 page, I wrote the word CAUSE in bold capitals. Then I put a jagged circle around it. Spidering out from this core, I drew three more circles and connected them to the main circle. Each of these smaller circles contained one of the following words: GENES, LIFE, TRIGGER.

This is the first step with all patients. To understand his condition, I needed to know three things: what part of him was born mad, how life strove to drive him further along the primrose path of insanity, and what singular event tipped him into the sweet lake of illogicality, where grim reality holds no dominion.

I looked up from my notes and stared at K, thrashing about in his chair. His arms and legs, strapped in physical constraints, showed signs of chafing. I called Sister Driscall back into the room. I told her to take K back to the ward, and to add more padding to his wheelchair prison.

Her eyes narrowed and she muttered something under her breath. She asked if I had decided which sedatives to administer. She held up an empty syringe, as a prison guard would grasp a truncheon.

I lost myself in this image and failed to respond.

“Doctor,” she repeated, pointing the syringe at me like a question mark, “which sedatives?”

“None,” I replied. “None.”

“But he’s out of control! We have to keep him tied down and watch him all the time. He’s a major drain on nursing resources. He’s-”

“Are you questioning my decision, Sister Driscall?”

“No, but-”

“No ‘buts’. And no doping. Now see to K’s body and leave me in peace to see to his mind.”

Previously, I have always adhered to the conventions of modern psychiatry. I’ve treated the unsightly symptoms of madness with medications, while simultaneously attempting the talking cure of psychoanalysis. K will be different. I’ll cure him without the pernicious use of chemicals. I’ll lay aside the psychoactive agonists and inhibitors that so mark and discredit twenty-first-century psychiatric care. Rather than treat the symptoms, I’ll find the cause. Rather than spraying pesticide on the leaves of madness, I’ll root out the weeds.

Later that afternoon, my Chief of Staff in his chemical wisdom, and no doubt prodded by Sister Driscall, saw fit to question the absence of psychoactives in my patient’s bloodstream. He recommended the immediate injection of a cocktail of chemicals - a dopamine-norepinephrine hi-ball. It was only with a little subterfuge on my part, which I won’t dwell on, that I managed to keep Patient K free of these “designer drugs”. I call them such because they would design a false personality and build it over the ruins of the real one. No - a thousand times no!

K’s cure will be a beacon to others, an example of the efficacy of psychoanalysis and the inefficiencies of drug therapy. The talking cure will replace drug therapy. The Freudians will rise again.

Chapter 2

Skeletons in the Cupboard

Let’s begin at the beginning, with a circled heading from my notebook, Genes. Our first step will be to explore the catacomb of skeletons that makes up K’s family history.

I do this not to entertain, like some latter-day biographers - who are indifferent to the truth and only search for scandal, like pigs snout out truffles. I dig up K’s family skeletons to better understand K. I exhume the past to breathe life into the present. None of us arrives on this planet without ancestors. Like it or not, we are made from their essence. We are the past, and the past is us. To borrow the words of Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Tracing K’s ancestry was not an easy business. K himself was in no position to provide any information, and few other family members could be located. Fewer still could be persuaded to provide even the most potted of family histories.

Of his father, nothing is known. K knew him not at all, and his mother knew him only briefly. Indeed, she terminated our first interview very abruptly when I laboured the point.

“My sex life is none of your feckin’ business!” she said.

“We are in the business of sex, madam,” I assured her. “Not the act itself, of course, but the post-coital analysis.”

The more I persisted, the more reserved she became. She clearly suffers from psychiatrophobia. The condition, of course, is incurable. In order to overcome her fear of psychiatrists, she would need to see a psychiatrist.

I tried to locate more distant relations, without success. The family line was withering, like a tree that stands in polluted ground. Without siblings or heir apparent, it’s quite possible that K will be the last of the line.

Having so few sources of information in the present, I have had to consult the official records of the past.

While once numerous enough, few of K’s clan made it to the third millennium. The family line was decimated in the 1930s - a victim of tuberculosis, alcoholism and a propensity to walk in front of oncoming traffic while staring at the ground.

K’s pedigree was, shall we say, dubious. Indeed, one must admit that, as one traced the family tree backwards, the number of illegitimate progenitors far outnumbered the handful of legitimate ones. Had he been born in an age in which such impediments to greatness were more highly regarded, he would have been doomed to a lifetime of lowly employments.

My investigations have revealed that, throughout the nineteenth century, St. Brendan’s Home for the Bewildered had many patients that bore K’s surname. One notable, Vincent (known as Venereal Vinny), was something of a minor celebrity at the time, since he had managed to obtain all known venereal diseases. One medical student of the time postulated that:

“The cornucopia of the ‘Diseases of Venus’ that afflict him so egregiously - several of which are still unclassified, and of which he is inordinately proud - may have been spawned and swam to life in the warty mucus of his onerous male member, a green and slimy thing the likes of which I fervently hope never to see again ... a rod of Satan tended to by hitherto unimaginable armies of pubic lice. The man is a hothouse for the cross-pollination of disease and must remain in sordid isolation, until quicklime can do its work and cleanse this city of the scourge of the O’ Donghaile penis.”

It was tempting to conclude that K was born mad. In that way, we could wash our hands of the case, like some pontificating geneticist. My instincts told me otherwise. I ordered a battery of exhaustive blood tests, which proved that K had no venereal diseases, inherited or otherwise.

I passed Sister Driscall on my rounds later in the day, and could not resist informing her of this new piece of information. She was in the process of changing the saline drip on Sister S, a nun who believes that God is telling her to commit acts of self-harm, which she calls mortification of the flesh.

“No VD!” I said, confusing both nurse and nun alike.

“What?” Sister Driscall said.

“Patient K, I mean. He doesn’t have VD!”

“I never said he did, Doctor.”

“But don’t you see? This means he wasn’t born mad. This means that he became mad. This is the crucial issue.”

“For the nursing staff, the crucial issue is that he requires 24-hour attention, Doctor. His howling at night keeps waking the other residents, even from the padded cell. I really think we should place the patient on medication.”

“Enough, Sister Driscall,” I said, silencing her with my palm. “Patient K needs no medication. My tongue will root out his madness. My lips will craft the words that cure him.”

Chapter 3

School Daze

K wasn’t born mad. Life drove him mad, but which part of it?

His days in primary school remain shrouded in mystery. When I interviewed his former masters, most of them couldn’t remember him.

His report cards offered little insight. They describe him as “quiet”, “rather quiet” and “very quiet indeed”.

He did make an impression on one of his teachers - a Ms M. Cunningham, whom I interviewed at length. She said K had “an exceptional talent for silence. He would sit, inert, at the back of the classroom, staring out of the window. If any thoughts ran through his mind, the world knew nothing of them, because he never shared them.”

K’s prolonged silence went unquestioned. Class sizes at the time were forty to fifty strong. As Ms Cunningham put it, “one closed mouth among forty quacking ducklings is not easily heard.”

Shortly after retiring, Ms Cunningham wrote a guide for primary teachers, but it was rejected by all major publishers, and then by all the minor ones. Convinced of the pedagogic value of her work, Miss Cunningham used her early retirement bonus to obtain several thousand copies of her opus from a vanity publisher. Now, she spends her time going from school to school, trying to sell them.

I will provide the reader with a short extract from the book, since her bellicose tone offers some insights into K’s early classroom environment.

[Taken from Ms. Cunningham’s ‘The War Room - How to Survive the Primary Battle Ground’]

Silence is golden. All primary teachers must take this precept as gospel truth. You are at war. At war with noise. Engaged in the never-ending struggle to maintain order and decorum in the classroom, to hold down the pressure-cooker lid, to beat back the anarchy that lies in the heart of every child monster.

Absolute silence may not be the stated pedagogic aim of the classroom, but it’s your only real objective. The only good child is a quiet child. In your lessons, aim to create the calm of the cemetery. The stillness of death is the only environment that is conducive to true learning.

“What is learning?” you ask. Let me put it plainly - is primarily concerned with instilling unquestioning acceptance of any and all absurdities: religion, politics, the worlds of work and pleasure. Civilisation itself. All require obedience to arbitrary laws and customs.

The aim of education is nothing less than the death of thought. An independent mind is the spark that could set the barn on fire. As a primary school teacher, your duty is to stamp out thought!

[End of ‘The War Room’]

I moved from primary to secondary school, from the Blessed Untouched Womb of the Immaculately Immaculate Virgin Mother’s School for Boys to the Bleeding Pelican National School for Boys.

I spoke first with K’s peers. Many pupils at the Bleeding Pelican felt that, in his last two years, K started to exhibit peculiar behaviour.

Many recall that he grew increasingly obsessed with vampires. This penchant for bloodsuckers is not strange in itself, since vampires have become the idols of the young, adopting a rôle formerly played by pop stars and religious and political gurus. Where once a poster of Che Guevara or Jim Morrison graced a bedroom wall, a gloomy vampire now stares down moodily. It is the rather morbid fashion of our times for teenagers to idolize creatures who feed on the blood of the living, in order to prolong their own time in the underworld of the undead.

K’s interest, however, went well beyond fashion. Even his best friend, Rasher Richmond, thinks that his interest bordered on the neurotic. Before quoting him, however, I should also point out that young Rasher has few admirers among the academic staff at The Bleeding Pelican. His physical education instructor described him as “mad, bad and dangerous to know ... and a complete maggot on the hurling field!”

[Excerpt from Rasher Interview]

“K got totally vamped out, y’know. Like Dracula City, man. It was all he’d talk about, day after day. It got so bad that no other sod would listen to him, bar meself. Even I kinda like zoned it out a lo’ of the time.

“I’d be scheming to roll up a spliff behind the bike sheds, laying down plans to stoke up some skirt come sundown, but Kev would be off in his own world, riffing on about some dead dodo called Barry Stoker. ‘You’ll never poke her with yeh Stoker!’ I told him. ‘Young birds don’t dig dem dere aul books, Kev.’

“He’d have none of it though. I remember him one day, boundin’ down the corridor, after smokin’ a ... an energy cigarette. He was holdin’ a different Twilight novel in each hand, braggin’ to every dozy scarecrow we passed that he was readin’ both books at the same time, ‘cos ‘neither one required more than half a brain’.

“And this other time he found some gormless first year, with his nose stuck into this mouldy aul paperback his ma must have given him. Something about Job Interviews for Vampires. K takes it from the beady little carrot top, and he writes a note on the cover for the brat’s ma to read. I memorised the note - it was pure K!

“’This novel is a rank corruption of its gothic forebears, with prose so degraded that the inky pulp would not challenge the mind of a squid’.”

[End of Rasher Interview]

Voices more reliable than Rasher testify to a second reading peculiarity. He would begin books on the last page, skip forwards to the beginning and end with the middle section.

Teacher G, of whom you will learn more shortly, was confounded by his idiosyncratic summary of Hamlet. It had him die at the beginning, then kill the new king, then interview the ghost of his father, the old king. It ended with Hamlet falling out with his mother and being banished to England, through a “plot wormhole”.

In a later lesson, outlined in the next chapter, he even attempts to prove that Hamlet himself was a vampire, and that Shakespeare too belonged to that same race. Even the Dark Lady of the Sonnets was none other than his Immortal Beloved, the vampire queen, Elizabetha.

When queried by his teacher on issues of temporal distortion, K stressed the need to adopt a non-linear approach to interpreting fiction. He wanted to highlight the curved nature of space and time; that time was bending fiction into a perfect circle.

“Time” he would say, “is a nightmare from which I am trying to escape.” He went on to claim that Joyce went forwards in time and stole this line from him. “The line only makes sense if spoken by a time-travelling vampire,” K insisted.

At this point, I would like to include an excerpt from a short story written by the previously mentioned Teacher G, who was K’s head of year during his final year. I believe it will shed some light into the cavern of the classroom he inhabited.

Teacher G, I should point out, like so many English teachers, entertains certain literary ambitions. He is hampered, in my opinion, by his strict adherence to what he terms “post-modernist ultra-realist fiction”, or “postmod ultrarealfic”.

This forbids the writer from following the traditional structures and strictures of standard fiction. Instead, he believes stories should mirror real life, which tends not to have neat beginnings and endings, since every day is merely a continuation of the last one. The conflicts, crises and fantasies of Monday are brought forwards to Tuesday, and so on ad infinitum. Or in Teacher G’s case, ad absurdum.

His novel-in-progress, ‘Short Story Diary’ - which he’s been working on for fifteen years and which won’t be finished until the day of his death - contains one chapter for every day of his life. The following extract is from Chapter 5021.

The reader may find the style a little rich in this episode, since G is going through what he calls one of his “gâteau periods”. I would urge the reader to stay the course. Although there is much froth here, there is substance too.

Chapter 4

The House of the Bleeding Pelican

[Extract from Teacher G’s ‘Short Story Diary’]

Chapter 5021

In the depths of the spring, a sluggish sun rose, like an alcoholic on a Sunday - slowly and with much fluid discharge. Its bloodshot Cyclops’ eye bled over my school, this House of Usher. Dawn killed night.

Vagrant brooding clouds ignored the sun and refused to change from black to white. Clouds killed light.

Beneath the muddled sky, the cold wind beat the yellowed grass. It lay frosted and forlorn, crying in dewy wakefulness. The blades wept for the death of night.

Beneath the grassy carpet worms quarried nitrogen with a wriggle, and sang ballads of better times. Worms wriggle so because they remember the days of the ancients, before the vertebrates, before the slaughter of the early morning. Rooks and ravens, listening above, plucked the doleful choir one by one and visited grisly death upon them. Birds killed worms.

The sun and the sky, the earth and the grass, the worms and the birds: they all agreed on only one thing and one thing only - they would much rather be somewhere else. God had cursed them with Dublin!

In the middle of this dreary plain, a building hunkered. A teen prison, a Stalag, a school.

I trudged towards it, wading through the afterbirth of a March dawn, before the clocks could strike nine.

With my head bent low, I slipped through the glass doors of the Pobalscoil Rozminions. I saw, above my head, the ever-watchful eyes of the Holy Bleeding Pelican, our emblem and our aneurism. “God is watching you,” the pelican warned.

I turned right, away from the eyes of the beaked and beatified bird. I headed for the teachers’ room, the arse of the apse. Upon arrival, I formally recognised the zombies within, the living dead who teach but cannot learn. We took turns to dispense the stale ritualised greetings of another moody Monday.

All around us, outside the church walls, teen demons howled for admittance, so that they might snash and slash, in the uterine comfort of alma mater slayer.

[End of ‘Short Story Diary’]

I shall break Teacher G’s description there, since the following fifteen pages are largely concerned with the rise and fall of an erection he experienced “on first looking into Miss Forrest’s blouse.” He muses long and hard on how the erection mirrors the rise and fall of Rome.

While it is a curious piece, which might prove useful in understanding Teacher G’s own subsequent ejection from the world of academia, it is not relevant to K’s case.

I have included Teacher G’s description of K’s secondary school only to give the reader an idea of the environment K suffered, prior to his psychosis.

I wanted to know how K felt about his own schooldays. I went to the horse’s mouth, but the horse in question was as dumb as the four-legged variety. This had to end. I determined to make the dumb speak.

Hypnotism proved completely ineffectual. The swaying of my watch and the soothing tone in my voice, only seemed to make him all the more irate. I ended all attempts to induce a trance-like state when he began to froth at the mouth.

At a loss on how to proceed, I resorted to Rorschach ink blots. While they didn’t result in anything as grand as a speech act, they did seem to have a calming influence on him.

It occurred to me to replace the ink blots with something more personal. I had Sister Driscall procure some photos of K’s school from the internet and I showed them to K.

They produced an immediate effect. His eyes widened, he took a deep intake of breath, and strange gurgling noises came from the back of his throat.

I hurried to press record on my Dictaphone, desperate not to lose a word of what I was sure would be a breakthrough moment.

I leaned the microphone towards him and brought the school photo closer to his eyes.

“Speak, Patient K. Speak!” I pleaded.

“Grr ...”

“Speak! By Freud and all the psychoanalytic lords of the mind, I command you to speak!”

“Aooooh,” he said, like a hound with a toothache.

“Speak, K. Say the first thing that comes into your head when you look upon this picture. What does it remind you of? What is the association? Free the association! Free your mind of this neurosis. Speak!”

Words failed him.

Instead, he communicated through phlegm. What I mistook for pre-vocal speech was actually the hawking of mucus. When he had a large enough amount of it, he ejected it from his lips. It flew across the space between us and landed at the top of the picture. The phlegm slid down from the sky and spread itself over the school and finally dripped onto my Persian rug.

Copyright © 2014 by Phillip Donnelly