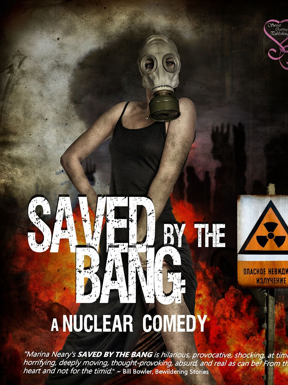

Marina J. Neary, Saved by the Bang

reviewed by Bill Bowler

Saved by the Bang Publisher: Sweet Cravings Publishing Date: January 7, 2015 Length: 200 pp.; 1,146 KB Vendor: Amazon Digital Services, Inc. ASIN: B00S06I97W |

There is a turn of phrase in Russian that means “laughter through tears.” Russian literary critics used the phrase to describe their reaction to the work of Nikolai Gogol, the great satirist, who happened to be Ukrainian but wrote in Russian. Reading Marina Neary’s Saved by the Bang, I found myself laughing through tears. The novel is razor-sharp, one could say terribly funny, hilarious, yet painful in its searing depiction of “the human animal” in all its misery and glory.

Like Gogol, Ms. Neary uses realism to achieve the absurd. Details, realistic in and of themselves, pile up to the point of exaggeration. When the scene, realistic in its parts, becomes absurdly exaggerated by the accumulation of detail, the characters’ reactions are unexpected, blasé when we expect something extreme, or extreme when we expect indifference.

The author makes masterful use of the ancient Greek rhetorical device peripeteia, the sudden reversal, the unexpected development. This introduction of the unexpected, this disconnect between stimulus and response, ratchets the satire up to a more intense level.

The reactor at Chernobyl blew up? Yawn. Just let me finish my nails. And yet, such absurdity is real. It’s the stuff of life. In the face of all odds and against all obstacles, the characters adapt; they cheat; they fight back; they switch sides and switch back; they love and hate; they muddle on; they survive or perish; they thrive after a fashion; they persevere; they triumph.

The characters, like the setting, dialog, and plot, are marvelously and wickedly depicted in a concatenation of unexpected and jarring detail by an acerbic narrator.

When Nicholas returned to Antonia’s room, he found her cuddling on the bed with her husband who was humming some bawdy Polish ditty into her ear. The sharp smell of aged musk permeated the air. Joseph had brought a flask of Scythian Gold perfume from Minsk for Antonia’s upcoming birthday in June, but in light of her recent brush with death, he had decided to give her the present early. That scent was hugely popular among entry-level courtesans who were sleeping with provincial officials, but respectable women like Antonia used it also without any detriment to their image. Musk is universal. Whores and wives of KGB agents alike turned into goddesses when they applied a drop of Scythian Gold to their necks. Apparently, the perfume contained a hefty dose of aphrodisiac, because Joseph was all over Antonia, his hand squeezing her breast through the faded hospital gown. Her toes peeking from under the blanket were wiggling and curling, signaling arousal.

Lily was fanning herself with the medical chart, her posture communicating resigned disapproval of such lascivious displays. Clearly, the surgery had not affected her daughter’s libido. Antonia had just had her reproductive parts nipped, clicked, rinsed out and reassembled, and she was already eager to resume her usual sexual activities. If given the opportunity, the shameless hussy would probably do the dirty deed right there in the hospital bed, in front her own child. Not that Maryana was paying any attention to her parents’ necking. She was too busy playing with her new Mickey Mouse watch. She would bring the wrist to her ear, listening to the faint ticking, and grin triumphantly. While Nicholas had been trying to beat the information out of the old abortionist, she had cajoled her father into buying the watch from the kiosk across the street from the hospital. The plastic trinket was not expected to last more than a week, but to her it symbolized victory over Joseph. Sometimes nagging and blackmailing worked.

The novel is set in Belarus, near the Ukrainian border. The characters are musicians at the local conservatory, their colleagues, husbands, wives, lovers, parents and children. The plot structure is East-European soap opera and focuses on human and family relationships.

Many of the events depicted are painful, even tragic: child abuse, coat-hanger abortion, adultery, deceit and envy, career opportunism, not to mention nuclear meltdown and radiation cancer. But the characters struggle through adversity, find ways to communicate with each other on some level, assert themselves, their identity and their humanity in the face of apocalyptic folly.

Not only is “nothing sacred” in the novel, it tramples on the sacred and holds it up to ridicule. Joseph Olenski beats his daughter Maryana, and Maryana exploits her bruises to manipulate her parents and get what she wants.

Another Russian turn of phrase comes to mind, also from Gogol. Back in 1815, as the Tsar, his ministers, and the rich and powerful laughed their heads off at The Inspector General, the mayor in the play turned and addressed the audience in Gogol’s famous apostrophe: “What are you laughing at? You’re laughing at yourselves!”

The same thing happens when you read Saved by the Bang.

Copyright © 2015 by Bill Bowler