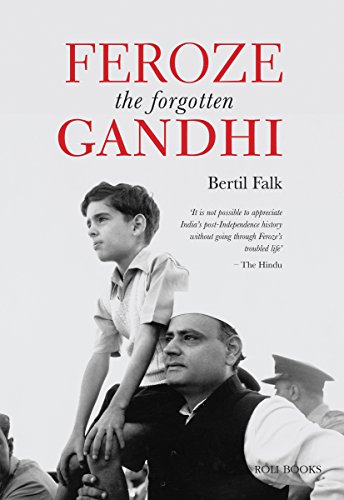

Bertil Falk, Feroze, the Forgotten Gandhi

excerpt

Feroze, the Forgotten Gandhi Publisher: Roli Books (November 17, 2016) Hardcover: 320 pages ISBN: 9351941760; 978-9351941767 Kindle: 6.6kb Reseller: Amazon Asia-Pacific (Nov. 29, 2016) ASIN: B01MTUEF3L |

Changing With the Times

When I started taking an interest in Feroze Gandhi, my only intention was to write an article about him in Swedish. When I came to understand his importance, I decided on a biography in English. Since he was born in 1912 and many people who knew him as a boy were either dead or very old, I concentrated my research on his younger days. But I knew that one day I would have to delve into the parliamentary records to know more.

Tarun Kumar Mukhopadhyaya anticipated me in this sphere in his scholarly work Feroze Gandhi: A Crusader in Parliament, where he has scrutinized, described and analysed Feroze’s activities in the Lok Sabha.

But how did Feroze’s stature rise in India? How did the freedom fighter from Allahabad, the joking gossipmonger of the coffeehouses, the member of the ruling Congress party and the silent backbencher of the Lok Sabha become a crusader and ultimately, someone who looked like an unofficial leader of the opposition in the Lok Sabha?

What Feroze Gandhi introduced in the Parliament after years of unobtrusiveness was, in fact, investigative reporting transferred from newspaper journalism to the floor of the legislative body. He was probably the only investigative parliamentarian in India, and I doubt he has had many or any counterparts in other countries who performed their task with such meticulous care as he did.

As Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson, research scholar and author Rajmohan Gandhi puts it, ‘Feroze’s secret was the homework he did, which yielded facts that abashed ministers.”1 And this is actually the reason for studying Mukhopadhyaya’s book, which is like a manual for an investigative parliamentarian.

After being occupied for years with disputable as well as indisputable gossip in coffeehouses, Feroze began to investigate hearsay. Suddenly he was in possession of a new tool. We know that ever since his childhood, he had been meticulous when it came to cleanliness, his clothes, bikes, cars, roses, furniture and the rotary press. Now he handled his gossip-driven ability to investigate, as if investigating in itself had been his bike or his rose garden or the rotary press of National Herald. When he at last decided to take the floor, he had done his homework. In the same way as a strainer separates the cream from the milk, Feroze now separated fantasy from truth, fiction from facts.

His old mentor and friend K.D. Malaviya, saw Feroze’s development over a period of thirty-six years. At close quarters, he watched him grow from an eager boy scout to an excellent parliamentarian. He tells us, ‘[T]here is no doubt that in the latter part of Feroze’s life when he became a member of Parliament, his personality grew fast. The qualities that were in him came up. Had he been spared to us a few more years, I have no doubt in my mind that his personality would have come out and shone more and more and the country would have known much more of the great qualities that were imbued in Feroze Gandhi. This I can vouch because of my knowledge of him.’2

M. Chalapathi Rau, who in many ways considered Feroze incompetent and useless, now and then saw a light at the end of the Ferozian tunnel. For once he wrote, ‘In India, as in Britain, it was being proved that the main aim of parliamentary democracy was effective parliamentary government, and this was achieved in India, without too much sacrifice of freedom of discussion or of the initiative of private members. Private members like Feroze Gandhi were more effective than ministers or leaders of opposition parties.’3

Rau was one of the founding fathers of twentieth-century Indian journalism and the creator, or at least the main spirit behind it, as well as the first president of the Indian Federation of Working Journalists. The journalists demanded the freedom of the press to report the proceedings of legislative bodies without any fear of legal actions.

But Rau does not even mention in his Journalism and Politics that it was Feroze who in 1956 saw to it that the demand of the journalists was met by the Parliament. There was no lack of intellectual power in the Ferozian performances between 1955 and 1960. On the contrary, at last Feroze had found his place in Indian politics. He swam like a fish in water. He now mastered politics as well as he had once mastered freedom fighting and gossiping.

When, on 23 March 1956, Feroze Gandhi entered the Lok Sabha rostrum to give his speech to initiate and make a powerful case for the Proceedings of Legislature (Protection of Publication) Bill three-and-a-half months after his maiden speech, he had twenty-five years of experience in jails and coffeehouses among leaders of the country and in the midst of socialists and communists in Britain and in getting arrested by the police in Paris.

He had been co-operating with the workers at the printing press, attending Congress meetings, repairing cars, tending flowers, loving food, admiring women, among other activities. He, furthermore, had behind him years of parliamentary experience.

Nevertheless, he could still play a trick, but now he did that in a very sophisticated way. This is his introduction when he pleaded to move the Protection of Publication Bill: ‘I am conscious that I stand in special need of the indulgence of the House because I am aware that the great privilege which has fallen upon me of presenting the Bill to the House arises from no merit and talent that I possess but from the engaging whimsicalities of our parliamentary machinery. I am not the sort of back-bench Member who enjoys having thrust upon him the duty of somewhat tedious exposition from a script. I am rather the sort who enjoys descending upon the House at rather infrequent intervals — the sort of back-bencher who existed in more spacious days — to castigate a mischievous minister and then retreating for several months. I am afraid, therefore, that it falls to me to request the indulgence of the House while I fulfil the very great privilege and duty of moving this second reading.’

Did Feroze say that? Yes, but no. For then he said, ‘This is not what I have to say. These are the words of N.H. Lever who moved the Defamation Amendment Act, 1952 in the British House of Commons. He, too, like me, sir — I am sorry, madam — was a private Member...’4

*

* *

About the Author

Bertil Falk (b. 1933) is a highly respected Swedish newspaper and TV journalist, who spent more than ten years of his life in India, England and the United States. His love in writing started with a short science fiction story, published when he was 12, he then did a few radio programs when he was 15 and got a mystery novel published when he was 20. Since then he has worked for different newspapers, primarily Kvällsposten (The Evening Post) and from the years 1987-1989 he was in the newsroom of the Swedish TV3 in London.

After retirement he has written about 35 books (fiction and non-fiction) and besides translating many mystery writers into Swedish he also translated and edited into English two anthologies of short stories by Swedish mystery writers. He was the editor of the cultural magazine DAST for a few years and contributed until recently for fiction as well as non-fiction to the internetzine Bewildering Stories.

He also filmed and produced video documentaries in Africa. For the past ten years, until recently, he produced community radio programs for Trelleborg Sjöormen Rotary Club, where he is a member.

Copyright © 2016 by Bertil Falk