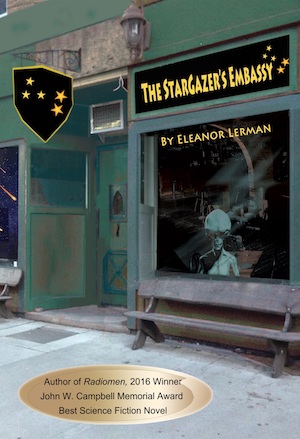

Eleanor Lerman, The Stargazer’s Embassy

excerpt

The Stargazer’s Embassy Publisher: Mayapple Press (July 1, 2017) Paperback: 310 pages ISBN: 1936419734; 978-1936419739 |

Summary

The Stargazer’s Embassy starts by slowly turning the frightening phenomenon of alien abduction around to see it from an unusual point of view: in this story, it is the aliens who seem fearful of the woman they seem increasingly desperate to make contact with. And they have reason to be: while the main character —Julia — has had these alien visitors in her life since childhood, when her mother apparently tried to “introduce” her to them, she has been violent whenever they come near.

Now an adult, with her mother long dead, Julia becomes involved with a psychiatrist who has himself been drawn into the alien abduction world. When he is killed by one of his patients who has been driven over the edge by her own abduction experiences, Julia nearly kills the “thing” — as she calls the aliens — who carried out the attack.

Fast forward to ten years later, and all alien abductions, everywhere, seem to have stopped. A journalist who had made his living by writing about and publicizing abductees and their experiences believes that Julia is somehow involved in this strange phenomenon and threatens to draw her back into harsh public spotlight she fled from after the murder unless she helps him figure out why.

Julia actually is involved and, though she herself doesn’t want to know how or why, she is going to have to follow her mother’s unknown path, which in this life — and perhaps the next — leads deeper into direct alien contact and a confrontation about what death means to humans and “others” alike.

The theme is rooted in the idea of alienation, no pun intended. What I mean is that the story explores how individuals, who strive for connection to other human beings, still so often remain alienated from each other; how different groups remain separated from each other; how workers are alienated from those above them; and how human and alien races, should they ever encounter each other — though perhaps they already have — will likely be unable to comprehend each other’s experiences and beliefs, particularly how we and they envision death.

It also touches on how children without mothers are like aliens themselves, feeling separate from the society they are supposed to belong to.

Part One: 1990

I

That August, I had a job cleaning a townhouse in Greenwich Village. It was a movie actor’s East Coast place; he’d had a party the night before and left the house a mess. In the afternoon, as I was trying to get red wine and God knows what other kinds of stains out of the carpeting in the living room, I had watched the actor’s handlers help him down the winding staircase — a coil of glass and wood that was hard to navigate even stone cold sober — and out the front door to where a limo was waiting to take him to the airport for a flight to L.A. No one said a word to me. Why should they? I was just the cleaning lady. Amid the scrub brushes and spray bottles of cleaning products, I probably looked just like anybody else. Of course I did. That was my goal.

The agency that sent me had told me not to show up until late in the day, so after the actor left, I had to work well into the evening. I labored diligently, as I always did, rarely stopping, paying total attention to every task I had to complete. I kept my headphones plugged into a CD player the whole time, listening to discs that I carried with me whenever I had a job. I didn’t much care what the music was; I had a stockpile of used CDs that I bought at flea markets, and just scooped up a random selection whenever I had to go to work What was important — what was always important when I was alone — was to keep my attention focused and my mind occupied.

By the time I finally finished my work and locked up the house, it was just about nine. The streets of the Village were busy, as always on a weekend; straight couples, leather boys, kids from the suburbs were all wandering in and out of the bars and restaurants and window shopping the hand-made jewelry and sandal shops that stayed open late. Usually, there would be a crowd hanging around Sheridan Square where the Christopher Street subway stop let out and gay dance bars faced each other across a small park, but that wasn’t so much the case tonight. Instead, I noticed that an unusual number of people seemed to be meandering west, towards the Hudson River piers. I suddenly realized why that was: this was the first night of the Perseid meteor shower. I had read about it in the newspaper last week. The arrival of the Perseids was always predictable but in the sodium glare of city lights, they weren’t usually as visible as they were expected to be on this clear, cloudless night.

Normally, the thought of making a detour to watch a meteor shower would never have entered my mind. I generally just tried to get from one place to another — home to work; work to home, mostly — by keeping myself to familiar routes and my mind on automatic pilot, as much as possible. Tonight, my plan had been to walk home from the Village, straight downtown rather than veering even a few blocks west, but it was a hot night and I didn’t have air conditioning. There would probably at least be a breeze down by the piers, so I decided to allow myself to follow the crowd of strangers heading towards the river. Even so, I didn’t plan to stay very long.

By the time I crossed over West Street, there were dozens of people hanging around the rickety Christopher Street pier, which pointed straight across the Hudson towards the construction sites where new hi-rises were being built on the Jersey side of the river. Some people in the crowd were drinking, some were smoking weed. A few policemen were strolling around, checking things out, but an amnesty for petty crimes seemed to have been declared for the night because even the cops seemed more interested in the coming light show than who was getting high on what. I imagined everyone was hoping that because it was a little darker down here, away from the streetlights, they would get a better view.

I found a spot on a bench facing the river and had been sitting there for about twenty minutes when I saw someone point up to the sky and yell out, “Here they come!” I tilted my face to the night sky but I couldn’t see anything much; maybe some thin streaks of light so faint that they seemed to be an apparition, more imagination than reality.

“Why don’t you try these?” a voice suddenly said to me. “You’ll be able to see much better with binoculars.”

I looked up to see a man standing over me. He had dark hair, a striking face — not handsome, exactly, but angular, serious — and was, I thought, considerably older than me. I was twenty-seven; the man offering me a very fancy looking pair of binoculars was, I judged, somewhere in his forties. He was wearing jeans and a green polo shirt; just a casual summer outfit. I always studied the clothes of anyone who approached me — I had to. Sometimes, it was my first clue about just who was coming my way.

But I knew immediately that this man wasn’t a concern to me. Still, I was disinclined to accept the offer until he smiled at me and despite myself, I let the smile disarm me a bit. I liked the smile, and actually, now that I was here, waiting for the meteor shower to really get going, I thought, Why not? What’s the harm? “Thanks,” I said. I pointed the binoculars at the sky and what I saw was a revelation; this first wave of nearly-invisible shooting stars became glittering traceries of light, bright trailways through the sky that existed for a few moments and then disappeared.

I watched these bursts of light live and die for a brief time, and then handed the man back his binoculars.

“Beautiful, aren’t they?” he said.

“I guess,” I said. “Sure.”

He looked amused. “You’ve seen better?”

“I used to live upstate,” I told him. “On a clear night, if you went out into the fields where there were no lights, you’d always see shooting stars. A meteor shower could fill the sky.”

I had spoken without caution, a mistake I did not often make, and so thought that perhaps I sounded like stargazing might be some particular interest of mine. Immediately, instinctively, a kind of recording began to play in the back of my mind, a denial that I had an interest in anything connected to stars or the far horizons of night and space. No, no, I would tell people when I was younger — anyone who assumed I might be interested in things like that — that’s not me, that’s my crazy mother. You know how she is. As a defense, a way of separating myself from her, I had learned to talk about my mother’s supposed interest in observing comets and meteors, along with the seasonal progress of the constellations across the night’s great, dark vault. That, I would swear, is what took her out of the house at night. That’s why you might see her walking on the road, I could say, heading across the fields, towards the woods. Hunters, fish, swans, dogs, scales and lions; I had made myself memorize the names and shapes of the constellations in order to claim that she had told me, that she knew them all.

“Where upstate?” the man asked me.

“Freelingburg. It’s near Ithaca.”

“Ah, the gorgeous gorges. It’s beautiful up there, but it does get really cold in the winter.”

So thankfully, all we were doing now was making small talk, this stranger and me. Well, that was a better direction for the conversation. Besides, I liked the idea that he had introduced the topic of chilly weather. On such a hot night, just the idea of lower temperatures brought some relief.

“By the way, my name’s John Benton,” the man said. “And you are?”

“Julia Glazer,” I told him.

“Well, Julia, would you like to go have a drink with me? We can wait out the Perseids until they decide to show up in full force. That won’t be for an hour or so.”

I thought about it and was going to say no until he smiled again. There was something about the way it softened his angular face that I liked even more now that I had seen it again, so I said yes. I even admitted that I was hungry.

I assumed he had some bar in mind, but instead, we ended up just walking across the street, where an enterprising vendor had set up a hot dog cart to cater to the crowd strolling down to the river. John bought a couple of franks and two bottles of beer from a cooler that the vendor had stashed under the cart and then we walked another half block until we found a stoop to sit on. This was all okay with me. It was nice. Just sitting around and having a casual talk with someone was not an experience I’d had much lately. Well, really, not for a very long time.

We talked some more, and I asked John where worked. I didn’t expect the answer he gave me, that he was a doctor. And then there was that smile again, though this time, it had an element of Cheshire cat about it. “Actually,” he said, “I’m a psychiatrist.” He waited a moment and then looked over at me with a raised an eyebrow. “Nothing? No reaction? Usually, when I make that particular confession, people either run away or start telling me their problems.”

I held up the half of the hot dog I had left and said, “I’m still working on this, so I’m not going anywhere. And I don’t have any problems.”

“That makes you the first person I’ve ever run into who doesn’t, but I’ll take your word for it.” He drank some of the beer and then studied the label for a moment, providing himself with a pause in which to consider what else to tell me. Finally, he added a little bit more to the biography he had just begun to sketch. “I see patients but I also teach. Or did teach. Taught.” Then he named a university uptown, so famous that even I had heard of it. “I head the department of psychiatry. Headed,” he corrected himself, looking rueful about how he was getting tangled up in his own language. “It’s a long story.” Maybe just to change the subject, he asked me, “And you?”

“I clean houses, apartments. There’s an agency that sends me out on jobs.”

“And?”

“And what?”

“What else do you do?”

Now it was my turn to smile. “You mean do I really want to paint or write or want to act and so I clean houses while I pursue my real calling? Well, no. Nothing like that. Really — I just clean houses.”

“That’s probably not what you went to school for, right?”

“School? Does Freelingburg high school count? They were still teaching home ec when I was there. Cooking and sewing. I can make a pie and mend socks if I ever need to.”

I knew what these questions were about. John Benton, the psychiatrist professor — okay, maybe not professor; there was certainly some kind of story behind those past tenses he was getting so tangled up in — was asking himself what he was doing sitting on these steps with me. He had picked up someone (which was exactly what was going on; we both knew that) who was obviously way too young for him and he was trying to figure out why he had done that. I was attractive enough, I suppose, even in my cleaning lady disguise of old jeans and thrift-store shirt, which on the street converted themselves into casual cool. I had straight brown hair, brown eyes — all fine, but not remarkable. So if I wasn’t remarkably beautiful or a secret ballerina, what was keeping Dr. Benton here, talking with me?

I decided to give him something, some hint that at least I had some kind of inner life. “I read a lot,” I told him. “And music. I almost always have music on.”

I pulled the CD player from my shoulder bag and showed it to him, evidence that I was a person who told the truth — sometimes, anyway. To my surprise, he took the device from me, just as I had taken his — the binoculars — from him. He opened it up to see what I was listening to.

“Mood music?” he said, reading the label. “So what’s your mood?”

“Oh, pretty mellow right now, I suppose.”

“Then you’re lucky,” he said. “I’ve spent the evening with people who definitely are not.”

He reached for the bottle of beer again and then busied himself with his food. I read this sudden turning of his attention away from me as a signal that even allowing such a slight hint about his work — the private problems of his patients, I assumed — was not something he usually did.

Like me, he recovered quickly from whatever lapse of judgment he thought he’d exhibited and we went back to chatting. He asked me what books I liked, what movies I’d seen lately, still trying to figure me out. Then he asked where I lived. I explained that I rented an apartment on Canal Street and then John told me about his place, an old, converted carriage house on Paper Lane, a few blocks away. The narrow lane, which was just the length of one city block, was still cobbled and it took its name from the printing businesses that used to be quartered there in the late 19th century. Now, there was still one press left — the Socialist Workers Party was housed in a small warehouse on the west end of the lane. On the east end, there was a recording studio that was famous for letting the bands who used the facility sometimes pay their fees in cocaine instead of cash. Either way, John said, he felt like he was living in the last bastion of an old Village culture: drugs, rock and roll, and outsider politics surrounded him from all directions.

We finished the food and the beer but kept on talking for a while. Finally, John suggested that we walk back to the pier.

There were even more people gathered by the river now, looking up at the sky, or just using the light show as an excuse to hang out at the edge of the Hudson. John and I sat on the bench where he had first found me and passed the binoculars back and forth between us as we tilted our heads back to watch the meteor shower. There were more of them now, dozens and dozens a minute, and probably many more that we couldn’t see. With the bright, lively sky overhead, the river lapping at the pilings and the soft buzz of conversation rising from the groups of men and women all around us, the night felt peaceful, pleasant. Even the meteors streaking silently across the sky seemed to be keeping quiet on purpose so they wouldn’t disturb anybody.

We sat and watched the sky for about half an hour, which was enough for me. I stood up and told John that I was going to go home. He wanted to get me a cab but I said I would walk, which had been my plan since I’d left the townhouse earlier in the evening. No, he told me, it was too late; he insisted on a taxi and that he was going to take me to my place.

We flagged down cab, but when we got in and I told the driver where to go, he looked puzzled. On the rare occasions that I took a taxi at night, the drivers always seemed confused or asked me if I had the right address because I was directing them to a neighborhood that, in those years, was a commercial area. It had no clubs, no nightlife, and as far as most people knew, no apartments. But I insisted that the driver to just go where I said; I must have sounded sharp, but John either didn’t notice or it didn’t bother him.

It didn’t take long to reach Canal. This wide street, where long ago there had indeed been a canal, was now lined with stores that sold industrial products — glass, plastics, hardware, tools, paint. They were all locked and shuttered at this hour. I lived above a store that sold uniforms and work boots, in a railroad apartment that had housed the original owner and his family when he had opened the business before the second World War. The place probably still looked much the same as it did back then: a living room with a kitchen off one end and the bedroom right in line after that. The living room faced Canal, the bedroom looked out on an alley and the bathroom still had a pull-chain toilet, but I had gone to some small lengths to make it look a little less like I was reliving someone else’s tenement days. I had painted the walls white, hung posters, draped Indian-print blankets on the couch (paisley prints in one living room, elephants and temple bells on the bed) and piled my books and tapes on wooden planks separated by thick glass bricks that I had found tossed out as scrap. The place was perfectly presentable, but — for a number of reasons — I wasn’t about to invite John Benton up for a viewing, or anything else for that matter. I said goodnight to him in the cab and stepped out, heading towards the door next to the store’s front entrance, which led upstairs.

But John called after me. “Hey,” he said. “Come back a minute.”

I knew what he was going to ask and I could have pretended not to hear him, but that’s not what I did, Maybe I should have just gone up to my apartment and these days, in a certain frame of mind, I might be inclined to hold long arguments with myself about what kind of difference, if any, that would have made to everything that happened later. Perhaps a lot. But in any case, that’s not what I did. Instead, he asked for my phone number and I gave it to him. Maybe he wanted to see me again for no other reason than to try to solve whatever mystery he thought was involved in his attraction to me, but I had something else on my mind, so it’s possible that I gave John my number just because I was too distracted to come up with a reason not to. There were other issues I had to deal with at that moment.

Facing my front door, I was facing the rest of the night, which meant I had to get to the top of the stairs and then down a long hallway to reach my apartment. The apartment itself had never been violated, but the hallway had been, more than a few times. Tonight, all I could do was steel myself for a confrontation but hope, as I always did, that nothing — literally, no thing — was waiting for me once I went upstairs.

II

John called a few nights later and asked me out to dinner. He suggested a restaurant on Jane Street, not far from his house, and I said I’d meet him there around eight o’clock. I had been on the Upper East Side all day, where I had two apartments to clean in the same building, so after I finished work, I took the subway downtown to my apartment and let myself nap for a while.

I got up at the hour when the stores were closing and the bumper-to-bumper traffic on Canal Street was beginning to ease up. Because it was so warm outside, I had my windows open, and I could hear cars and trucks rumbling along and even the voices of people walking beneath my living room window as they headed home. The sky was streaky, blue on blue on blue, displaying a small moon shaped like a thin white disc, rising as slowly as if it wasn’t sure it was really supposed to appear tonight. It was easy for me to feel isolated and a little lonely at such an in-between time, so I turned on the lamps in my apartment and put on the radio to try to lift my mood. And then I tried on clothes, hoping to find something that didn’t make me look like a cleaning lady playing dress up. My closet didn’t provide many options but I settled on black jeans and a black top. The outfit was a little severe looking, but it was going to have to do.

I got to the restaurant a few minutes late, and found John waiting outside. He was wearing slacks and sports jacket over an open-necked white shirt — the doctor at ease, I supposed. We looked unmatched, in age, in dress, in everything. And yet, once we sat down, just like the other night, we fell into easy conversation.

John told me a little bit more about himself — he had been born in Chicago, had done his medical training at Harvard, come to New York to do his residency and then never left. He had been married, was long divorced, and had no children. In addition to seeing patients, he told me that recently, he had been writing and publishing a lot — mostly articles in various magazines and journals, though he had also just started a book. When I asked about what, he said, “Oh, I guess you could say I’m considering the mysteries of human experience.”

I waited for him to elaborate, but he didn’t. I wasn’t going to pry, so I turned my attention to the menu. Maybe then John thought he should tell me a little bit more, so he said, “I’ve written a book about depression and another on the treatment of mental states that manifest hallucinations and behavior predicated on hallucinatory directives, but I guess I’ve gone off into some unchartered territory now — both in my writing and my research. Which is why I’m not teaching at the moment. The university takes its Ivy League status very seriously — and its fundraising. So, they would rather that I stick to more standard pathways.”

“Can they actually tell you what you can do?”

“I certainly don’t think so. That’s why I have a lawyer who’s trying to work things out with the academic review committee that’s been set up to evaluate my work, as well as with the president of the university — he’s not too thrilled with me, either.”

|

The waiter came to the table and we ordered food and wine. When we were alone again, John said, “So now your turn to tell me about yourself.” He took my right hand and turned it over, so that the inside of my bare wrist was exposed. “Let’s start with that tattoo,” he said.

The tattoo. I’d had it since I was a child: two dark blue circles separated by about half an inch from three smaller circles, all inked with points, like Christmas stars. It had long ago occurred to me that if you connected the three small stars, the result would be an almost perfect isosceles triangle.

“My mother did it,” I told John.

He seemed to need a moment to process what I’d just said. It was a measure of how comfortable I was already feeling with him that I’d even mentioned this fact, which I usually kept to myself; I’d told other people before and I was aware that it seemed peculiar. Well, more than aware, really — when I was growing up, the kids around me made sure I knew that. When I was a child, nobody had tattoos except bikers or guys who were in the Navy. Mothers certainly didn’t go around tattooing designs on their little girls. But then, my mother was different. Everybody knew that, but especially me.

“Your mother?” John said, sound incredulous. “Why in heaven’s name would she do that?”

I shrugged. “She had the same thing on her wrist and she said that it made us both special. She told me that she read about how to do it in a book. The ink is actually some kind of plant dye; it never seems to fade. I’ve had it since I was about six or seven.”

John looked at the tattoo again, seeming to study it. Then he looked back at me. “She must have been an interesting person, your mother. What’s her name?”

“Her name was Laura.” I said.

“Was?”

“She died when I was thirteen.” I rushed on, not giving John a chance to say he was sorry about that and he didn’t try to interrupt me. “But yes, she was an interesting person. She always had her own ideas. Her boyfriend, Nicky said she was a hippie before there were hippies.”

Now I could tell that John was doing mental calculations in his mind. “She must have been very young when you were born.”

“She was seventeen. I was born in 1963, in Rochester, and from what she told me — which was never very much — her parents kicked her out. After that she — we — lived in a couple of different towns upstate until she met Nicky and ended up in Freelingburg. I was about eight years old by then. He owned a bar and she worked there. We had an apartment upstairs.”

“So you’re still living above the store.”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” I said, picturing, first, my bedroom above the bar and then my rooms on Canal Street and the uniform store downstairs. There really wasn’t a similarity, but still, it made me wonder if I wasn’t being analyzed. Gently, maybe, but analyzed all the same. I looked over at John and asked, “Are you maybe in psychiatrist mode?”

“I don’t think so, but if you do, I promise to stop,” John said genially. Then he asked, “Did you ever meet your father?

“Nope. He was some high school infatuation of my mother’s. I got the message that she wasn’t interested in connecting with him and I wasn’t really, either. Nicky was around for most of my life and he was a good guy. I mean, he was always very nice to me. I didn’t feel like I was missing anything. We still keep in touch. After I graduated from high school, I might have even stuck around except there really wasn’t much for me to do in Freelingburg. He did ask me to stay; he said he’d be happy to pay me a salary to work at the Stargazer’s Embassy, but...”

John suddenly interrupted me. “He would pay you to work where?”

“The Stargazer’s Embassy. That’s the name of the bar.”

“I love it,” John said. “It’s a wonderful name.”

“It was Laura’s idea,” I told him. “When she met Nicky the place was called the Whiskey Wind or something like that. But Nicky changed it for her.”

Impulsively, I reached into my shoulder bag, which was hanging over the back of my chair, and pulled out my wallet. Tucked into one of its compartments was a piece of laminated cardboard with my name written on one side under the word “Passport,” which was stamped in big, block letters. Printed on the other side was the following information: Official Document. Issued by the Stargazer’s Embassy to the World. Underneath, in dark blue ink, was a mirror image of my tattoo: the two dark blue stars with the three smaller ones off to the left. I showed it to John and he laughed. “I guess you all had a whole script you were working from up there in Freelingburg. Though it is taking the joke a little far to brand your own child,” he added.

As I put the passport back in my wallet, a feeling came over me that I decided was embarrassment, but maybe really wasn’t. Why did I hold onto that thing? I asked myself, probably for the millionth time. I had such mixed feelings about it and everything it represented. Sometime after he changed the name of the bar, Nicky had begun giving them out to customers, but had presented me with the first one. I remember that even as I took it, I wasn’t sure that it was something I wanted. And yet, here it was, with me still.

I led the conversation elsewhere. John told me about a trip he’d taken last summer to New Mexico to interview a Native American tribal leader named Richard Killdeer, who had spent hours talking to him about shamanistic practices and beliefs. “One of the things he told me,” John said, “is that we are all capable of traveling though time and space. He said that human beings have always known how; they’ve just forgotten. He said that if you ask the moon to invite you, it will and your spirit will fly away for a visit, just like that. I was thinking about what he said when we were watching the meteor shower the other night; I wondered if I was watching traveling spirits instead of just interplanetary dust.”

As John talked about what Killdeer had told him, the tension in the sharp planes and angles of his face seemed to relax; his whole aura of intensity seemed to lighten. It was obvious that he was talking about something he found fascinating.

“Is that what got you into trouble at the university? Are you doing research into things like that?”

“That’s a part of it,” John said, and I assumed he was answering both my questions. “But it’s a little more complicated.”

Again, he didn’t seem to want to say any more on the subject, so I didn’t push. We talked about other things for another hour or so, through dessert and more wine. Finally, as he was paying the bill, John asked me if I had to work the following morning and I said no; I didn’t have a job the next day.

“Then come back to my house,” he said. “There’s a garden. We can sit outside and have another drink.”

We walked the few blocks from Jane Street to Paper Lane, and if he hadn’t shown me where the top of the lane was, between two longer streets that ran east-west from the river to Sheridan Square, I wouldn’t have realized it was there. Halfway down the cobbled lane was a heavy wooden door set in stone façade; again, it was something I would have missed if it hadn’t been pointed out to me. The squat, square stone building, with dark stained glass windows on the second floor, hardly looked like a cozy place to live.

But inside, everything was different. The front door opened into a small vestibule where a straight-back chair sat beneath a framed canvas on which some artist had painted bands of sea green, one on top of another, like layers of a summer ocean. This was a waiting room; beyond it, another door led into John’s office, which held a desk and a more comfortable-looking chair than the one outside. There were no more paintings because the walls were all covered by bookshelves that held hundreds of volumes along with an assortment of artifacts that included a woven basket, decorated with a zig-zag pattern, that appeared to be wind-weathered and well-used; a small ceramic vase as deep red as the rug; and a stiff-legged metal horse that looked like some kind of totem object. Yet another door led into the main area of the house, which was smaller than I had expected. There was only one bedroom, and that was at the end of a hallway; just beyond the office was a kind of sitting room that did, indeed, open onto to a small garden with a square of paving surrounded by flowering bushes and potted plants, all enclosed by the brick walls of the surrounding buildings. Inside, showing me around, John led me up a short flight of stairs to the second floor, which, he explained, had been a hayloft at the turn of the century — this was, after all, a carriage house. Here, there was a small kitchen with a trestle table and two wooden benches, a living room with a television on a stand, a well-used couch and two armchairs all covered in dark yellow corduroy. The stained glass windows, which went from the floor to the ceiling, were the replacement for the original hayloft doors.

I loved the house from the first minute I entered it. There was something about it that reminded me of Freelingburg, an old north central New York town with a two-block main street where most of the buildings had a history that reached back before the turn of the century. And like John’s carriage house, they were all reclaimed from some earlier purpose: one had been the company store for a now long-abandoned mill; another had been a bank that made loans to farmers. But by the time I lived there, as a child, the businesses that had replaced their outmoded ancestors — the “new” hardware store, the produce market, the pharmacy — had themselves become obsolete because a depressed economy and changing times had driven many of the locals out of their small upstate towns. From the Hudson Valley to the Finger Lakes region, people were leaving and businesses were closing up shop.

It was only the Stargazer’s Embassy, under a dozen different names, that had survived in its original incarnation. It had always been a bar — after all, everyone drank; the mill hands, the farmers, the mid-century workers who drove to the factories in nearby towns. But just as it seemed to be in its death throes, Freelingburg — and in particular, the Stargazer’s Embassy — was born again because of the influx of hippies and back-to-the land types who started moving up to central New York State in the 1960s. Cornell University in nearby Ithaca also provided new customers for the bar. Bikers mixed with the long hairs who mixed with disaffected professors marking anthropology papers in the corner, nursing a Genesee Cream Ale.

I had a complicated relationship with Freelingburg; it was home but it was also a place where I had been deeply unhappy. And angry — viciously so. But from the first time I saw it, the carriage house on Paper Lane seemed to soothe those feelings, which I still nursed. The wood and stone, the iron fittings on the doors, the beamed ceilings and creaking floors reflected the same long, repurposed history as the houses of Freelingburg, but in its current incarnation as John Benton’s home, these elements of the house combined to make me feel at ease. Not safe, exactly — I was never safe; that I knew well — but for the moment, I was willing to settle for standing down from the constant state of alert that was my usual condition. Sometimes, when I was working, or plugged into my headphones, or lost in a book, the needle on the internal meter that measured my level of watchfulness would move down to middling. Tonight, though, when John and I went back downstairs and I settled myself into a chair in his walled garden, with just a small square of late-night summer sky above me, I closed my eyes and felt almost relaxed. The meter was hardly registering any disturbance at all.

John brought out a bottle of wine. We sat for a while and had a drink, then, without either of us saying a word about our intentions we went inside, to bed. I hadn’t slept with anyone in a long time and I got the feeling that neither had he, but the attraction between us was strong, and from the beginning, I think we both knew this had already gone far beyond whatever we had — he had — originally thought was happening between us. This felt serious. It seemed so very quickly.

His bedroom, probably the horses’ tackle room once, was small, and so was the bed, which meant that when we finally fell asleep, we continued to be entangled. I liked that, I liked feeling his arms around me, I liked feeling the strength of his body, even deeply at rest. I slept for a few hours; whatever dreams I had did not linger with me when I woke around three a.m. John was lying on his side now, facing away from me, but still close enough that when I slid out of bed, I was careful to move as slowly and as quietly as I could so as not to wake him.

I put on his shirt, which was too big for me but comforting, as if we were still enveloped in each other. But why was I awake? I went upstairs, to the kitchen, and drank some water. I opened the refrigerator and ate some grapes out of a bowl. But I was neither hungry nor thirsty, and I knew it. I also knew where I was going next.

Down the stairs, out into the garden. A familiar sense was pulling me: the state of high alert was back. The needle on my internal meter was threatening to push past the edge of the dial. That hadn’t happened since the night I had met John, though even though I had felt some inward tremor of concern when he’d left me on the street outside my building, the rest of the night had been uneventful. I had gotten upstairs and locked the door behind me without incident. But that was days ago. That time was past. I knew this time was going to be different.

It was dark outside as I entered the garden, but there is always ambient light in the city. People are up late and their windows blaze; the sodium glow of streetlights is ever-present; cars drive up and down the streets with their headlights pushing through the heaviest hours of the night. So I could see well enough in the small, enclosed garden to make out a figure standing in a corner just at the point where the walls of two of the surrounding buildings met.

It was wearing a long, ill-fitting tan raincoat with prominent epaulets and a pair of what looked like white go-go boots. On its head was a baseball cap pulled low over its face, and it had completed this ridiculous outfit with a pair of oversize sunglasses that might have been worn by some would-be glam rocker a decade ago.

“Is this what you think people look like now?” I snapped at the thing.

The thing — my own word, the only one I would use to describe these beings — took one step away from the shadowy corner and made a high-pitched sound that varied in tone. Perhaps, as always, this was some attempt at communication, but I never understood what was being conveyed and I had no idea if they understood me — though that didn’t compel me to keep silent.

“I’ve told you and told you,” I said, “You and all the others. I don’t care what you want from me. I never have. I never will.”

And then I turned away and went back into the house. I would have slammed the garden door, but that would have awakened John, so I just quietly closed it behind me. But before I returned to bed, I found my shoulder bag and removed my CD player so I could fall back to sleep listening to music. In the next moment, though, I changed my mind and put the device away. Instead, I just wanted to fold myself back into John’s arms, hoping that would be enough to take my mind off the thing in the garden, which was probably gone by now anyway, since they never seemed to hang around very long. And it was hardly about to come into the house because then it would have to show itself to John and I knew it wouldn’t want that. It — they — never did. I was always alone when I saw them; I was the one they always approached, never anyone else I was with though of course, I rarely was with anyone else. Except now, maybe, I was.

As I slipped back under the blankets and closed my eyes, I conjured up a picture of the carriage house and imagined myself moving through its rooms, talking to John, doing everyday tasks, simply living my life. In this scenario, the things not only stayed outside, they grew so tired of my ignoring them that they stopped showing up — though perhaps by the time I invented that possibility I was already asleep and the story I was telling myself was just a dream.

Copyright © 2017 by Eleanor Lerman