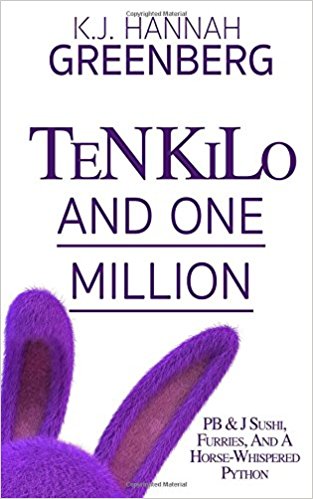

Channie Greenberg, Ten Kilo and One Million

excerpt

Ten Kilo and One Million Publisher: Crooked Cat Books Retailer: Amazon.com Date: July 29, 2017 Length: 174 pp. ISBN: 1974026698; 978-1974026692 |

Synopsis

Until she collected one million dollars, mild-mannered Professor Tabatha Davis knew no one-eyed, steampunking oncologist, ate no anatomically correct marzipan, and paid for no Catalina Islands trip. Nonetheless, after winning a furmeet’s jackpot, she became shadowed by a second rate media crew, befriended by a peanut butter and jelly sushi entrepreneur, and blamed for the python strangulation of a horse whisperer. What’s more, she was abandoned by her cat, stumped by infatuations, nearly killed by a draft horse, and coerced to lose ten kilo. Tabatha’s snort-chocolate-milk-through-your-nose-funny story entertains with stoned visual artists, with wild thespians, with random academics, and with a confused HVAC technician, while, most importantly, challenging the worth we attribute to fortune and fame.

* * *

from Chapter Two:

Whistling in Chicago

Maggie moaned as she reached for the bucket. After slopping her guts therein, she dabbed at her head with a damp cloth. It was December and her boatswain had long since become history.

“More crackers,” Maggie ordered. “I will barf without salt.”

Tabatha slanted her eyes at the behemoth that had displaced Mr. Phillips. Though Beverly’s reptiles had sometimes frightened her cat, it was a onetime Furry who had succeeded in completely vanquishing him. Maggie had claimed, in an exaggerated southern accent, that felines harbor toxoplasmosis and that toxoplasmosis is deadly to unborn children.

While Mr. Phillips looked relatively happy chasing mice amidst the malodorous haze that wafted through the ceramicist’s digs, Tabatha missed his sneezes and his tendency to uproot her windowsill herbs. Neither Maggie nor Beverly snored into her face as had that cat and neither of her human roommates had ever offered her as much as half of a dead crow.

On the ceramicist’s side of the wall, no one paid much attention when Mr. Phillips sat on their work. Over and above, those artsy types released him outdoors on his command and gave him the best vitamins and cat food money could buy. That they deducted all of those purchases from their rent money was not their concern.

Neither Mr. Phillips nor Tabatha grasped that those performers were fattening him up in order to stuff and mount him. Theirs was an ongoing search for the ultimate in visual expression. One among their crew, who had espied Beverly’s albino boa, would have readily made a plaque out of the snake had it not been for the small pistol, and a license to use it, both of which the veterinary assistant possessed.

Chicago was that year’s Rhetoric and Semantics Conference destination. The urban planners, who had had the foresight to understand that persons stupid enough to accept the Windy City as an airline hub would also be stupid enough to flock to meetings there, had made sure that the city built a surfeit of hotels.

No urban planner advertised, though, that the area’s blustery, lake weather made Chicago as desirable, in December, as Tampa was in the summertime. Nothing needed to be said; the same parties that regularly scheduled Boca Raton for the Syntax Society’s July meetings, regularly reserved space, in Chicago, for the Rhetoric and Semantics’ wintertime congresses.

“I’ll feed her and make sure she wears her slippers,” Beverly promised as she tried to shove Tabatha out the front door. “Bring us back snow globes.”

Tabatha grunted about the agathusian habits of both certain Greeks and of certain friends. In that moment of rhetorical glory, she missed that her front door had already slammed shut and that behind that access both the girl who liked animals, and the girl who like men dressed as animals, were struggling over her television’s remote control.

Regardless, until she passed the highway’s Springfield exit, Dr. Davis pretended she was commuting to the university. After passing that exit, she tried to imagine herself as a young professor driving to the airport for a conference flight. Tabatha nearly hit the sixteen-wheeler in front of her.

She was no longer a professor and she no longer had an academic future. Also, because of her tenant, she had almost failed to leave her driveway. When Tabatha was warming up her engine and defrosting her windows, that man had run outside and had jumped into the passenger side of her car. He had pressed into her hand a copper and enamel key chain shaped like a grove of New Hampshire birch trees. He had palmed a small zip bag full of herbs into her carry-on, too.

“The key chain’s good luck. The cuttings are Mexican oregano. Mom’s a healer. She taught me that oregano’s flavonoids and phenolic acid make wonderful antioxidants.”

Tabatha glared, glanced at her watch, and tried to shoo the ceramicist away.

“I’m not just a potter, you know. I took my first degree, in chemistry, from M. I. T.

I had a wee problem, there, with an explosion that cleared out half of the life science’s wing, so I declined a graduate fellowship. I was going to study organometallic chemistry. Instead, I made peace with glass and clay. My work still relies on high temperature ovens.”

Tabatha nodded, and promised to take the tributes. She released the brakes.

“They’re not for you; they’re for a friend, a friend from school, from chemistry. He worked at The University of Chicago, in the Biology Department, but now he’s dying at John H. Jason Hospital. Nasty type of cancer.”

Copyright © 2017 by Channie Greenberg