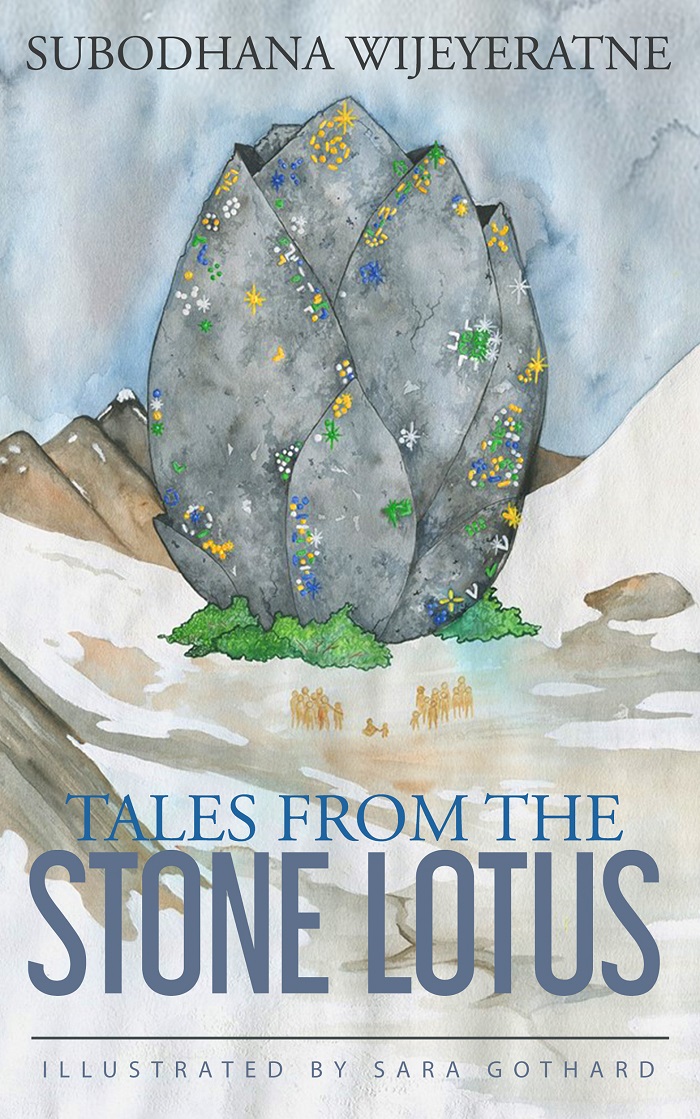

Subodhana Wijeyeratne, Tales From the Stone Lotus

excerpt

Tales From the Stone Lotus Publisher: The Writingale Publishing Date: October 15, 2017 Retailer: Amazon.com Length: 312 pages ASIN: B0755BKZYT |

From "As Kazanuhr Falls"

Rushung

Rushung sits under the twin moons, thinking of his home.

How different these southern reaches are to the steppes, he thinks. In the north the wind bites and the land is hard and the ponies’ hooves leave only the most fleeting of trails in the tough grass that clings to the dust like dirty green fur. The trees are gnarled and the beasts fierce and by now winter will have already arrived in a fit of screaming storms. When he closes his eyes he can see the icicles hanging like giant daggers from the beams of his house and the snowoxen huddled for warmth in the snow outside, like boulders with horns.

His pony tugs at its reins, and he snaps back to the present. He pats the creature’s thick neck.

“Hush,” he says. “Hush’.

The creature subsides, but world around them does not. It is still summer here, though late, and the air is full of insects. The breeze skims over knee-high grass, setting it rolling in waves. Still, he thinks, it is better than where they have been. Better than the cities they have burned, in kingdoms stinking of sin. Better than the gutters and parapets where people fought to stay unfree.

He uncaps the bottle at his side and takes a sip of rice wine and nudges his pony forward. They follow a chuckling stream down into a shallow valley. Farther along, where it widens into a rolling basin, is a city of yurts. Dotted between these are small fires and a few large ones and swarming in their unsteady light is a multitude of shadows-ponies and men and women and mammoths and snow-rhinoceroses and, clustered together behind a giant palisade of spiked tree trunks, two de-winged dragons, rumbling as they sleep.

He sets the pony cantering down the main path, past cages full of slaves and sacks of booty. He cannot stand to look at any of it. He just closes his eyes and imagines his wife by the hearth, and his daughter next to her, staring slack-mouthed into the flames, a finger in her nose. No, that is not right. She is nearly fourteen winters old now, a marrying age. Already married, perhaps.

One of the women in the cages is sobbing. He halts his pony and stares at her. She sees him looking and buries her face in her hands.

“It’s fine,” says Rushung. “You’ll be alright. We aren’t permitted to mistreat slaves.”

The woman doesn’t say anything. Rushung turns his pony around and rides back out of the camp.

A mile or so away-far enough that the sounds of the camp have dwindled to a distant murmur-he finds a man sitting alone on a knoll, staring up at the stars. He draws his sword and rides up to him. Then he realizes who he is and slips out of his saddle and kowtows in the grass.

“Rushung of the Skelian Arnay humbles himself before the Messenger of God,” he says.

The man looks down at him. Skinny-faced and large-eyed and his chin capped with a fringe of hair that reaches down to his waist. He smiles.

“Sit,” he says.

Rushung ties his pony’s reins to his hands and sits at the man’s feet.

“What did you say your name was?”

“This one’s name is Rushung, lord,” says Rushung

“Are you tired, Rushung?”

Yes, thinks Rushung. Exhausted. In my bones. At the heart of me.

“No, my lord. We are well-rested, since Kiwupan.”

The Messenger of God nods. Then he looks up again.

“The strangest thing of all in your world is not the peoples-for we had those also in my world,” says the Messenger of God in a voice like the crackling of a low fire before dawn. Rushung leans in and loses himself in it. “And not the animals. What is strangest to me are your skies. In my world we have stars also-the Almighty in his wisdom put them there so we may know the time of year and many things besides, simply by looking at them and using mathematics. You do the same here.” He pauses, and leans back. “But here I see nothing familiar. I see no pictures I know. I have been told of your constellations, and they are beautiful, but sometimes I long for something I know.”

Rushung says nothing.

“You wish to return home, do you not, Rushung?”

“This one wishes to see his family again, lord.”

“You have children?”

“A daughter.”

“And your wife?”

“From the mountains, lord. This one wooed her but as this one was from the plains her father made this one win her in a competition of archery. Our daughter was born fourteen winters ago. She was so small this one did not take her outside for a month for fear that the cold of the spring would chill her into a little pillow of ice.”

The words come and he does not regret saying them or think for a second that the Messenger of God might not be interested. The Messenger listens intently and when Rushung is done he reaches out with a cool hand and squeezes his shoulder, once, hard.

“That sounds like something well worth returning to, Rushung of the Skelian Arnay,” says the Messenger. “Ten years is a long time. I too wish I could go home and see familiar skies. But He is with me, Rushung, and He is telling me to keep going. Golden and full of love, righteous and all-embracing, the only salve for our sins, each of which he sees and forgives and loves us despite them. His is a mind beyond understanding and yet we, insects as we are, a given little drops of His grace like nectar.’

So you are saying that we will not go home, thinks Rushung. So you are saying that we must stay here, and wreck, and reave, and topple.

“Yes, my lord,” says Rushung.

The Messenger of God chuckles, and gets to his feet.

“Now. We did not meet here by chance. I have a task for you. I am told you stalk well and are difficult to evade.”

“Whatever you command, lord.’

“There was a kondraumin who escaped the last city we seized. He is not far from here, and wounded, and he is heading for the next village, to find a horse. He carries information with him. Details of our numbers and our weapons.”

Rushung looks back over his shoulder but the camp is indistinct in the distance. He cannot see the palisade or the dragons from where he is.

“You wish me to find him, my lord?” he says.

“Yes. Find him and slay him. Do you see yonder star, between those two peaks?”

Rushung sees it, winking between the hills, a wan and tremulous thing.

“Yes, m’lord.”

“Follow that star.”

“This one shall obey.”

The Messenger pats him on the shoulder again. Then he walks off without another word, hunched and stumbling. As if something vast and heavy was weighing on him. Or else as if he was so distracted he had forgotten how to.

Maybe it is both, thinks Rushung. He is, after all, the Messenger of God.

The star is inconstant company and disappears behind the slightest wisp of cloud or puff of dust or at the first watery hint of dawn. Rushung follows it to the mountains and then along a steep pass slathered with moss with great slabs of stone protruding on either side, nude and jagged-edged, through the green. On the third day he is in a ravine and looks up and for an instant he sees a goat silhouetted against the sky, splay-legged and mid-jump, hundreds of feet above him. It is the only creature he sees for days, though he hears the call of eagles circling on the wind and the screech of rodents high on the inclines, signaling to their families that some strange beast has come stumbling through the valley.

He picks up his quarry’s trail on the second day, but it is only on the fifth that he finally sees him. He is riding one of the long-legged horses of the empire and from its tracks he can tell that it is hurt, that it is female, that it is young and not quite broken in yet. It is faster than his pony, but it will tire, and they have time.

He pats his beast on the muzzle.

“How’re you holding up, old friend?” he asks.

The pony flicks its ears and looks away. As if to say, I am not one of those demon horses of the south. I do not speak. And you know as much as I do that if I could, you would have killed me long ago. So stop asking me questions, and let’s get to hunting, you hairy bastard.

His quarry does not know he is being followed, or else he would not light a fire, thinks Rushung. By the seventh day he is close enough that he can see it burning, a little reddish nub amidst the spearing black silhouettes of some firs. He thinks of sneaking up in the dark, but it is too far.

The man heads off at dawn and Rushung sets off after him. His pony’s thudding footfall echoes off the valley walls and just after the sun rises the kondraumin emerges into a flatland studded with scrubby brush. He looks back. An instant later he urges his horse forward and the creature takes off in an explosive gallop, trailed by a billowing cone of dust.

Rushung smiles and tightens his reins.

“Come on, fatty,” he says.

He guides his pony off to the left, out of the dust, and digs his heels in. The creature tenses and sets off at a canter and though it is not as fast as the horse it can keep this speed up for hours, Rushung knows, without complaint. Already the distance between him and his quarry is opening, but he knows this will not last. He will have him by sunset.

He closes his eyes and gives himself up to the rhythm of the ride and the lick of the hot wind on his face. For a few moments he is home in the spring, with vivid green tentacles of life reaching up from the damp soil and bears waddling like hairy drunks down to the rivers to fish. He is riding out of the valleys into the river-plains, southwards, where great herds of shaggy ponies swarm over the grass, wild and near-impossible to tame. The air is tangy with the scent their dung. He and his friends are riding alongside them, whooping and tossing a skin of wine from one to another, knowing that if they dropped it they would have to finish the whole thing and return home drunk and be beaten by their wife.

The kondraumin’s horse begins to flag after an hour. An hour after that, Rushung strings his bow and fires. The arrow falls short. Twenty minutes later Rushung fires again. The arrow just barely misses the horse’s rump. An hour after that, Rushung fires, and the arrow thuds off the kondraumin’s helmet.

The man sits up, looks back, and draws his sword. He loops his horse around and dismounts, blade glinting like a thin mirror, and straps a shield to his arm. Then he points at Rushung’s pony. The creature halts dead in his tracks and Rushung flies over his head and lands on his neck in the dust.

“Dammit,” he hisses, clambering to his feet, sword ready. The kondraumin twirls his blade and circles Rushung slowly and the golden sun motif on his shield blazes in the hot light almost as fiercely as the thing itself.

“Nisan kani,” says the kondraumin. He flicks down his visor and it is a leering face, large-toothed, nostrils flared, and eyes wide and empty like a ghost’s. “Nisan kanyeri.’

“I don’t understand you, heathen,” says Rushung. He hefts his blade. “I don’t understand anything you’re saying.”

They watch each other for a moment. Then Rushung charges. He has barely taken five steps when the kondraumin holds out his hand and something colossal crashes into Rushung’s chest. An instant later he is flying back the way he came, arms akimbo, his blade spinning off towards his pony. He lands in time to see it bury itself in the creature’s neck. The beast falls thrashing to its side.

The kondraumin falls to his feet, wheezing. He fiddles with his helmet and rips it off and vomits onto the ground.

“You bastard,” says Rushung, scrambling for his blade. “You killed my pony, you prick.”

The kondraumin is not listening. He crawls over towards his horse, hand glowing. Rushung reaches his blade and turns and charges again but again the kondraumin holds out his hand and again Rushung flies back. A moment later the kondraumin’s horse takes off with a whinny, galloping in a straight dust-churning line towards the horizon.

Rushung gets to his feet, blade in hand.

“Shit,” he says.

Now the kondraumin gets up too, grinning, wiping the vomit from his mouth, and Rushung realizes that it is not a man at all, but a woman. Not a woman-a girl. Not a fully fledged kondraumin, then, but a page. That is why she is so exhausted. That is why when he charges her again she cannot knock him back. That is why after a few moments of clashing he can drive his sword with ease through the side of her neck. She falls, gargling, leaving swathe of blood like a giant stroke of red calligraphy on the dust.

Rushung waits for her to stop moving, and then searches her body. There is nothing on her, no scroll, no paper. Then he looks at the horizon, where the horse is now just a tiny dusty fleck in the distance.

He sits on the hot dust and sighs.

“Shit,” he says.

Copyright © 2018 by Subodhana Wijeyeratne