The Day I Hit Sulaiman

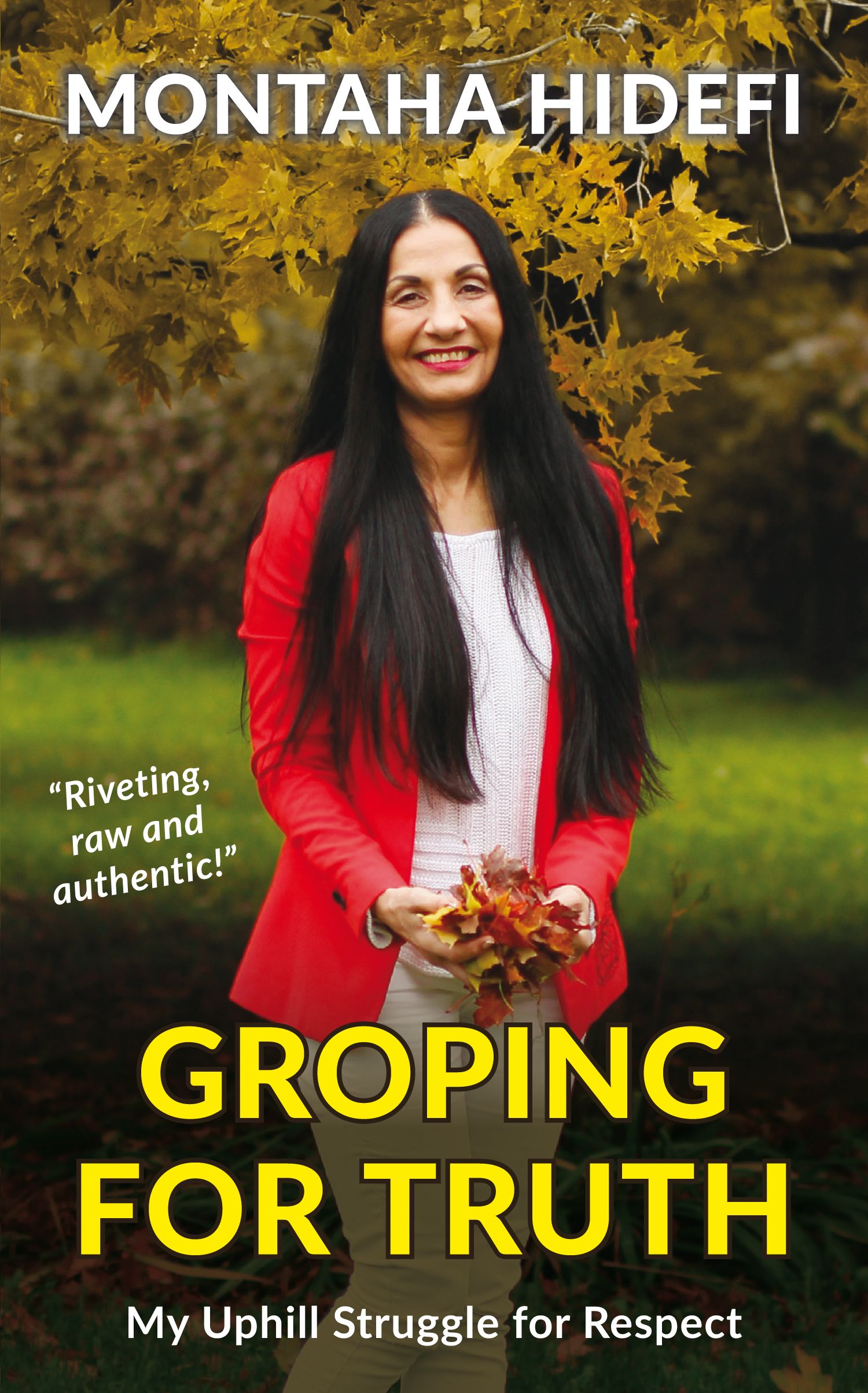

by Montaha Hidefi

|

One scorching summer evening in San Fernando, Venezuela, in August of 1965, Mother went out to buy caracol, a mosquito-repelling incense, and a refresco, a soda, to quench her thirst. She asked me to accompany her.

The hardware store — quincallería — that sold caracol was at the other end of the block, five minutes away. The bodega selling the drinks was another five to ten minutes further down the road, on Santa Ana Street.

As we reached the entrance of the quincallería, a black hearse followed by many cars passed by in a funeral procession. It was not the first time I witnessed a funeral procession. However, for some mysterious reason, this one piqued my curiosity. As soon as we entered the quincallería, Mother ordered the caracol from Mr. Chung, the owner. Mr. Chung fetched a green package and placed it on the counter.

At that specific instant, I shouted, “Chino, quien se murió? — Hey, Chinaman, who died?”

Mr. Chung got so infuriated by my question he picked the package off the counter and chucked it at my face while yelling, “Tu misma! — You did!”

The force of the package hitting me was so strong it propelled me backwards. I did not understand Mr. Chung’s reaction to my innocent question. All I wanted to know was who died. I did not know then that calling him “Chino,” as we referred to him at home, was a racial slur.

I picked up the caracol package from the floor where it had landed and threw it back at him with all my might. I quickly turned towards the door and said to Mother, “Vamonos! — Let’s move!” and ran out of the store. I did not look back and never set foot again in Mr. Chung’s quincallería. Mother, who was expecting to give birth to her sixth child at any moment followed me out, feeling embarrassed and confused.

I scampered down the sidewalk, shaking with fury. Mother yelled for me to slow down. When she reached my side, she demanded an explanation. I could not deliver one. All I knew was that Mr. Chung went too far in mistreating a five-year-old child because I had asked him an innocent question.

We continued walking in silence until we reached the bodega. Mother was tired, her legs swollen, her pregnant belly overhung. She allowed her heavy body to rest on the tightly woven, red rubber of the Scoubidou chair outside the bodega and ordered two bottles of Orange Hit, which was the name of Fanta in Venezuela.

We sat in silence sipping our refrescos while Mother looked distressed. The bodega did not sell caracol, and she desperately needed it to repel the relentless mosquitos. On the way back, Mother was exhausted. By then, I was in a better mood and told her I would get the caracol next morning from another bodega.

The next morning, when I got up, I could not find Mother. I ran towards my parents’ bedroom at the back of the store. The door was open. I stepped in and saw Mother lying in bed, looking weary, with an irregular-shaped light blue bulge looking like a bursting burlap bag on her right side. I stopped, confused. Mother asked that I come to her. I walked slowly until I reached the bedside. She uncovered the bulge to reveal the face of a little, sleepy baby.

“Last night, while everybody was deeply asleep, a white stork came in from the skies and dropped your brother wrapped in a light blue flanella blanket on my bed,” she said. “Can you see how beautiful he is?”

Perplexed, I glimpsed at the baby to make sure his face had not been smashed by the drop. It was the first time I had seen a baby boy, and he was my brother.

I delicately leaned forward to have a better look at him and smelled the pleasant scent of baby talcum emanating from this cherubic creature. His face was not smashed. On the contrary, he was sleeping like an angel.

“Your brother’s name is Sulaiman,” Mother whispered.

In Arab cultures, bringing forth a male offspring used to be — and continues to be in many societies — the ultimate and most significant goal of a couple. Males carry forward the clan’s heritage and preserve their House’s name through history and time.

Despite their dreadful economic condition, my parents continued having children with the hope of bearing a male child. Sulaiman was the sixth child. Mother was shunned by her in-laws for bringing to life five consecutive females. She was outrageously considered to be of an inferior reproductive blood-line. She felt under pressure to keep reproducing until she had a male, even if that meant a dozen children.

My sisters Danela and Yusra were in Syria when Sulaiman was born. Two years earlier, they had been sent to Syria in the company of Tio Salman’s family. Father felt it would be best for them to spend time with our grandparents in Al-Kafr and attend school to learn Arabic. Soon after Sulaiman’s birth, Danela and Yusra returned to San Fernando as they were considered a burden and a liability that the family in Al-Kafr didn’t want to deal with. In addition, Mother needed help to cope with the new baby, the other children, Father and the store.

To put food on the table for a large family, Father purchased an industrial sewing machine, installed it at the back of the store and learned how to produce cauchos, ponchos. The cauchos were made of synthetic black, and sometimes brown, leather, probably two metres square in size and were destined for the vaqueros, cowboys, to wear while working the ranches and riding their horses in the rainy season. To help Father, Danela and Yusra also learned how to sew and worked hard next to Father.

The arrival of Sulaiman changed many things at home, especially for me. I noticed that Father treated him differently from the way he always treated us. Sulaiman was being gifted with little toys and, once he started walking, Father started taking him to the abasto, supermarket, an activity that was not permissible for us girls. During the journeys to the abasto, Sulaiman could have whatever he wanted, no matter the price.

On one occasion, Sulaiman came back from the abasto with a cluster of white shiny things in his hand.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“Grapes,” he replied.

Venezuela is not known for growing grapes. At the age of six, I had never seen or tasted grapes. The white, greenish transparent colour of the fruits looked so enticing to the palate and appealing to the eye, I wanted to touch the skin of the grapes and savour one. Sulaiman was extremely generous, and he gave me two or three grapes. I took the grapes in my right hand, my intense look almost penetrating their delicate skin. I brought my hand under my nose and took a deep sniff.

The soft, earthy scent had a hint of freshly smashed green grass, which made me think I was in the park down the road, where I used to play. I must have waited a long while before inserting the first grape into my mouth. I closed my eyes and lifted my tongue up smashing the grape against the roof of my mouth. The subtle skin of the grape shattered under my palate’s pressure, dispersing its pulpy sweet membrane onto my taste buds. I was thrown into a place I never knew existed; a garden of flavours and colours. I would never forget that instant and I fell in love with grapes that day.

Later, I started improvising tactics to obtain a share of the goodies Sulaiman was bringing from the abasto. I seized the notion that being a boy was totally different than being a girl. Being a boy meant being taken to the abasto, being gifted a variety of fruits not accessible to girls, being gifted a tricycle, being dressed and scented differently and being loved differently.

It wouldn’t be wrong to presume those were the days that set the foundation for my rivalry and further rebellion against my brother and parents.

My rebellion against the family’s new living conditions began exhibiting itself first with unfriendly behaviour that escalated into hostility against my little brother.

I could not understand why Sulaiman was being given better treatment than me. No one at home was concerned about me or my feelings, and I never received an explanation. The more affection Mother and Father wrapped Sulaiman with, the more rejected I felt and the more hard-headed I became. I was so envious of Sulaiman that all I wanted was to get rid of him or become a boy like him.

One day, I was so upset because Sulaiman did not want to share with me a bar of chocolate, I ran after him around the back yard bearing a metal squeegee in my hands. He was running in front of me shouting for help. By the time Mother came to the rescue, I had knocked him on the head.

It was a minor cut, but the bleeding had alarmed the entire family. Mother, storming and menacing, shouted, “Inagsek ala umrik! — May your life be short!” She picked up Sulaiman from the ground and took him inside to take care of his wound. I felt satisfied, yet petrified, of what my punishment would be.

Gradually, I instinctively discerned that I was not Mother’s most favourite child. I was aware I looked ugly in comparison to my sisters and behaved differently from my siblings, but I was too young to understand if the exclusion was due to my dark pigmentation, my skinny body, my almond-shaped eyes with double eyelids or because I always operated at a hyper level.

The physical punishments inflicted by Mother escalated from isolation in the corner of our dining room in El Tigre, to whippings on my tiny legs with my own black nylon belt that I wore over my white school uniform in San Fernando.

Mother would hold me by the left arm and strike me until red blotches swelled up on my legs like purple dragon tree leaves. My sisters would then tease me by singing in Spanish, “Le florecieron!” which meant “her flowers have blossomed.”

This new type of punishment was psychologically tougher than being secluded in a dark corner, because it left distinctive marks visible to everybody at home and at school. So not only was it physically painful, but it also produced emotional wounds that would bleed on my memory’s walls for years to come.

The day I hit Sulaiman, I remained alert, expecting Mother to come for me to draw more purple leaves on the back of my legs. Hours later, when I had almost forgotten about it, Mother emerged from the kitchen carrying the black nylon belt. My sisters’ murmurs alerted me: I jumped off the sofa where I was sitting in the family room and started running around the house. Mother ran after me. We were dashing about and squealing like two wild boars, from the bedroom to the kitchen and across the hall to the dining room.

The six-seater rectangular, wooden table, covered with a colourfully embroidered, white table cloth, occupied most of the space in the middle of the dining room. I spun left and right around the table while Mother tried to catch me, again yelling, “Inagsek ala umrik!” and “Badi idbahik! — I will kill you!”

After many revolutions around the table, I felt I was about to get cornered. There was a slim opportunity for me to escape the clutches of my infuriated, abusive Mother, so without thinking of the consequences, I turned behind me and punched the glass fascia of the dark wooden cupboard with my little fist.

The punch was so robust that half the orderly-placed glasses and china dishes went cascading down and crashed on the polished concrete floor. Mother could not believe her eyes. Neither could I. I took advantage of the distraction and fled the dining room.

I sprinted across the back yard, scattering the hens and rooster pecking around the yard, until I reached the pond where our two pet ducks swam peacefully. I took a seat on the tarnished old barrel turned on its side against the red block fence that separated our back yard from the outside world. The rusted barrel served as a hatching nest for the hens and sleeping area for the ducks. It took me several minutes to calm down as I gulped and gasped to catch my breath.

Distressed and apprehensive, I could not comprehend then that my aggressive and destructive behaviour, particularly towards Mother, was an unconscious response to years of psychological abuse and physical punishment inflicted upon me.

I remained in the yard with the hens and ducks for many hours. I contemplated what a fortunate life the poultry enjoyed, not having a mother who openly hated or mistreated them.

I recalled then, one time three years earlier, when Mother almost killed me.

For mysterious reasons, there were days when Mother was so irritable and unapproachable, she could not even tolerate seeing me and my two younger sisters, Rasmille and Mima, playing around the house or making any noise. When we did, she would shout at us to stop. She also got easily infuriated and started big fights with Father.

That day, as I was playing with Rasmille and Mima in the bedroom behind the store, Mother shouted from the living room for us to stop the noise. I continued playing, ignoring Mother’s demand. I did not hear her coming down the hall, but when she walked inside the bedroom I saw the black nylon chancleta, sandal, she clutched in her hand and knew what that meant.

As I sat on the barrel reminiscing about that day, I could still feel the sting of the last slap from the chancleta on my back. She had chased me around the family room invoking the usual wicked prayer “Inagsek ala umrik!” and adding “Inshallah bit mootee! — I hope you die!” It was difficult for her to run with one shoe on, so she paused and threw the chancleta down, slid her foot in it and started running after me again. When she got hold of me near the entrance to the kitchen, she threw me onto the floor and started kicking me.

“No! Stop!” I screamed. “I will not do it again!”

Thinking about that incident, it is possible that at that specific moment, Mother was reliving the events of the night her father found her hiding in the potato sack and kicked her until her ribs almost broke. Maybe her inability to face her father then and her repressed resentment were being channeled against me as a way of retribution. But even then, this behaviour could not be justifiable.

No matter the reason, lying on my right side on the floor, I was practically being kicked to death! Mother’s foot, chancleta on, then landed on my fragile neck. It was then that I felt I was choking under the heavy pressure of her foot.

“Mootee! Mootee!” she was shouting while I was slowly being strangled.

I could feel the blood vessels on my forehead and temple begin to bulge. I thought I saw a black devil hovering above me as the chancleta kept me nailed to the floor. The more I resisted, the more I lost the capacity to breathe. I was immobilized under the weight of Mother’s hatred.

The crowing of the rooster brought me back from the terrifying memory.

I looked around me and took a deep breath in relief, realizing I was still alone, surrounded by the poultry. I closed my eyes for a second and remembered how Father, who had been alerted by the commotion, came to my rescue. He had come rushing from the store to find Mother choking me. He pushed her aside, reached down to pick me up in his arms and placed me on the couch almost unconscious.

“How could you do such a thing?!” I heard him yell.

As always, they ended up in a huge fight. Father retreated to the store, and Mother disappeared inside the kitchen, crying, while I lay on the sofa, gathering my breath.

That was the first time my father saved me from my mother’s infernal tentacles.

I stayed in the open-air shelter until the panic created by that awful memory faded, the sun plunged onto the horizon and the ducks went inside the barrel.

I then slowly walked back into the house and to the girls’ bedroom, trying to avoid Mother, who by then had completely calmed down and was preparing dinner in the kitchen. I sank into the hammock hanging in the middle of the bedroom and fell asleep.

Copyright © 2020 by Montaha Hidefi