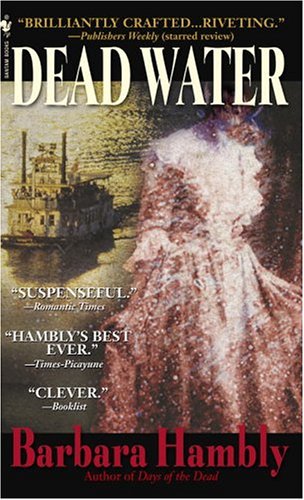

Barbara Hambly, Dead Water

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

|

|

Dead Water

Author: Barbara HamblyPublisher: Bantam Dell, 2004 Hardcover: $24.95 U.S. Length: 297 pages ISBN: 0-5553-10964-2 |

To me, it seems as though Hurricane Katrina has done more than flush New Orleans with the filth of oil and sewage laden storm waters. Before the wind exposed the ineptitude and unreliability of its politicians and police force, before revelations of its poisoned race relations and brutal murder rate made the watery invasion seem like some kind of divine retribution, New Orleans was a magic place to me. I’ve never been there, of course. Perhaps that’s a good thing. Shambala and others cities of our hearts are often better kept dream than reality. I know now what tarnished fact would do to my fantasy.

But my mother spent a good part of her childhood in Louisiana, and it was her stories that made New Orleans a fabulous place to me, burdened with a mystique that only San Francisco, of any other American city, could match. In my nostrils I can smell the peppery aroma of chicory coffee; in a hot night scented with honeysuckle an enigmatic black coach pulls away from a fanciful iron gate; black men with gleaming horns at their lips play the inexplicably merry notes of When the Saints Go Marching In as they stroll away from the newly filled graveside. There was something about New Orleans as alien and inexplicable as an artifact taken from an ancient African tomb. It was at once both the most American of our cities and the least.

I have to thank Barbara Hambly for giving me back that sense of wonder that I once associated with New Orleans. In the pages of Dead Water, nineteenth-century New Orleans comes alive just I imagined it. In the humid streets of the city that was already old by the 1830’s, the races mix with a fatally easy fascination for each other. That mingling of culture and genes forever changes both, and like metals fused in a fiery cauldron, something new and unguessed at is formed out of their heat and friction. In Hambly’s story we can see the crucible that both nurtured and destroyed slavery and its evils. There is the whole cast of characters here, from the gullible abolitionist waving tracts promoting freedom for slaves and vegetarianism to the two-footed beasts who sold other human beings for profit and those prepared to die to stop them. There are all the ordinary souls caught in the middle of some of the greatest events of our nation’s history.

This is no more than a background to an involving mystery, though. Benjamin January is a black free man, but as any immigrant to American shores knows, there are no guarantees that come with freedom. January is an educated black man, a musician and a Paris-trained surgeon. But with the freedom to earn one’s own precarious living comes the deadly consequences of failure. America, then and now, exemplifies St. Paul’s warning if he will not work, he will not eat, more than any other nation.

So when January is offered a chance to remove the heavy breathing of the wolf at the door (and to fund the small school he and his wife have started), he takes it. A bank official has absconded with a hundred thousand dollars in gold and securities. The president of the bank wants the money back quietly, and fast, before the word gets out to depositors. There’s a nice sum in it for January, who’s earned himself a small reputation for being the man to turn to in private problems of this kind.

But to get it, January, his wife Rose, and his partner, the opium-wasted, Latin-quoting white musician Hannibal Sefton, will have to follow the trail of the thief up the river. Up the river means that January has to leave the relative freedom of New Orleans for lands whose cane and cotton plantations require an endless supply of slaves. Soon January and his two companions are involved in a cat-and-mouse game of bluff and counter-bluff played out on the cramped confines of the steamboat and the raw river ports it docks at. Where is the stolen gold? Which of January’s fellow passengers are confederates of the larcenous bank official, and which are scheming to steal the loot from the thief... and to kill anyone who gets in the way? When the thief’s dead body is found tangled in the paddles of the steamboat, there are more candidates for the murder than January can keep track of. By the time January finds the key to this mystery, there’s been more than one murder done...

Many of you will recognize Barbara Hambly’s name from her many fantasy and science fiction works. I think I enjoy her continuing series of mystery-thrillers featuring Benjamin January more than her (generally excellent) speculative fiction works. Beware, though. The story isn’t for the faint of heart; much of Hambly’s works have an element of horror, and Dead Water is no exception. There are some raw scenes (and language) in this story. It’s probably true it would be impossible to write realistically of that era without some disturbing scenes; the de-humanizing of our fellow man into an object of monetary value is one of the most evil deeds homo sapiens has ever committed against himself. I wish such discrimination were an evil of only the past. But if Ms. Hambly’s characters are to be taken as examples, we can have hope there will always be those who speak up against such horror.

And in the meantime, that fantasy New Orleans, in all its dark mystery and edgy glory, is once again firmly in my mind. I just need a time travel machine to reach it. Thank you, Ms. Hambly!

Copyright © 2006 by Danielle L. Parker