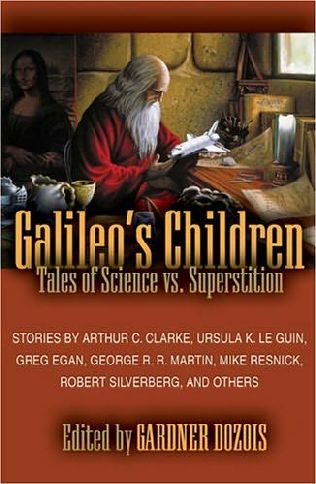

Gardner Dozois, ed. Galileo’s Children:

Tales of Science vs. Superstition

reviewed by Lewayne L. White

|

|

Publisher: Prometheus (Pyr), 2005 Hardcover: $25.00 U.S. Length: 346 pages ISBN: 1-59102-315-7 |

“I do not feel obligated to believe that the same God who endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect intended us to forgo their use.” — Galileo Galilei

With the above quote, Gardner Dozois opens the preface to Galileo’s Children. It’s the first sign that this collection won’t be simple religion-bashing with science always victorious, rather it offers further evidence of the unfortunate entanglement of the two.

There are a few stories with a straightforward assault on progress by religious forces, most notably Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Stars Below,” in which an astronomer is burned from his home and forced to hide in abandoned mines.

A few others, like Brendan Dubois’s “Falling Star,” in which an aged astronaut eventually faces an angry mob, and Edgar Pangborn’s “The World Is A Sphere” in which a future society wrestles with ancient knowledge that conflicts with current belief, have a similar theme, but more interesting execution.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Star” we have the viewpoint of a Jesuit priest / astrophysicist / astronaut as he uncovers an event that for him “proves” the existence of his God, or at least reinforces his waning faith. For me, it had essentially the opposite effect. At the very least, it made me wonder what would make that particular version of God appealing.

Mike Resnick’s “When The Old Gods Die” tackles the transition from superstition to science by tossing a “European” (white) doctor onto a space colony created as a Kirinyaga (Kenyan) utopia complete with an ancient shaman who uses curses, herbs, and spells. It also addresses the effect of progress on a culture’s dependence on religious faith for its identity.

Conversely, Robert Silverberg’s “Pope Of The Chimps” shows progress (by boosting the intelligence and language skills of primates) begetting superstition, as the chimps develop a religion with their scientists/observers as gods. The story also shows how easily, by accident or intent, superstition can be manipulated for good and evil.

Chris Lawson’s “Written In Blood” provides an interesting use of science as the ultimate show of faith by enabling the Koran to be “written” genetically into the blood of believers.

Continuing the blood/religion theme, James Allan Gardner creates a world in which the Catholic/Protestant schism may be biological in “Three Hearings On The Existence Of Snakes In The Bloodstream.” In both “Written In Blood” and “Three Hearings...” the genetic imprint of religion poses the risk of faith-targeted bio-weapons, though the authors handle the common theme differently. The protagonist in “Written...” undertakes the task of scientifically protecting believers despite her own lack of faith in her father’s god. The final protagonist of “Three Hearings...” (also a female scientist) finds herself caught in a Cold War-style buildup, with Catholic/Protestant-specific weapons instead of nuclear arms creating the risk of Mutually Assured Destruction.

One of the most unique takes on the religion/superstition theme comes from George R. R. Martin’s “The Way Of The Cross And Dragon.” An alien archbishop (an interesting concept in itself) sends his human chief Inquisitor to yet another planet to investigate rumors of a heretical sect called the Order Of St. Judas. The Inquisitor’s discovery shakes not only his own faith, but his understanding of the origins of religion, and perhaps the very nature of Truth and Lies.

One story I found to be particularly relevant to our times, but ultimately unsatisfying was “The Last Homosexual” by Paul Park. In this story, religion again serves politics. With the help of Creation science and Christian genetic theories, corrupt politicians of a dominant religious party have concluded that immorality (i.e. obesity, chronic poverty, theft, homosexuality, and whatever else offends those in power) are symptoms of disease. To stop the spread of viral immorality, the “contaminated” are isolated in facilities which bear striking resemblance to zoos. Apparently, no one works very hard at finding any cures.

Also included are: “Oracle” by Greg Egan, which features a C.S. Lewis-like Christian apologist author, and a scientist he fears has made a deal with the devil.

James (Dr. Alice Sheldon) Tiptree’s story “The Man Who Walked Home” in which a scientific experiment gone awry gives rise to superstition, then faith, as the survivors of a post-apocalyptic Earth come face to face with the title character.

And Keith Roberts’ “The Will Of God,” which I regret not having the chance to read before the book was due at the library.

Though a bit uneven, “Galileo’s Children” is an impressive collection, packed with well-known authors and great ideas. It has the potential, as with any great science fiction, of changing minds. Unfortunately, as is also the case with great science fiction, the anthology preaches to the converted.

The people who most need to read and learn from Galileo’s Children are those least likely to do so.

Copyright © 2006 by Lewayne L. White