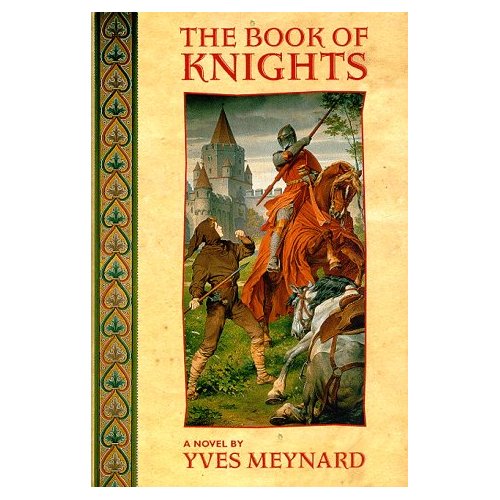

Yves Meynard, The Book of Knights

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

|

|

The Book of Knights

Author: Yves MeynardPublisher: Tor, February 1998 Hardcover: $21.95 U.S. Length: 222 pages ISBN: 0-312-86482-5 |

Quick! Mention a French-Canadian writer. Oops. Mention a French-Canadian anything (blush if all that comes to mind is maple syrup). Those of you from western Canada are probably mumbling something under your breath about separatism. South of the border, some of us are thinking dourly about that Hamas-handshaking, gladly-departed Jean Chretien. Does it sound like we need some happier associations?

Thank goodness for those happier associations. Yves Meynard is now writing in English. I hope he keeps it up, because I’d hate to have to work on my schoolgirl French just to read the rest of his books. But it might be worth it. The Book of Knights is Meynard’s first fantasy book in English, and thank goodness he decided to bust through the Gauloise Curtain. He has at least six previous French language books to his credit, and after I finished The Book of Knights, I picked up my dusty French language dictionary and wondered...

In The Book of Knights, little Adelrune is a foundling, an original sin he’ll never quite shed in the rigid, Puritan-like constraints of the village of Faudace. His step-parents have done their best for him. They’ve ensured Adelrune knows the Rules, Commentaries, and Precepts by heart, and that the rod is applied with stern measurement, never too much or too little. Adelrune knows how to sit without fidgeting or interrupting. He understands a found toy might lead to temptation and should be removed. Outwardly, he’s dutiful enough that his step-parents dream he might one day become a deacon.

But unknown to them, two events de-rail Adelrune from the straight and very narrow. First, in his stepparents’ dusty attic, he finds a magic book — the Book of Knights, of course. There is Sir Tachaloch, naked and tormented by monsters. There’s a giant in the teeth of an even larger beast. Mystery, terror, and concepts the Rules never really explain — honor, valor, sacrifice, and chivalry — are there to intrigue little Adelrune. Oh, it’s too late for the stepparents’ dreams of deaconhood. Adelrune is determined to be a knight.

But a knight-aspirant needs a quest. What noble goal will convince Riander, the mystic teacher of the Book, to accept Adelrune as his student? Fate soon provides Adelrune with his purpose. One day, lingering at the window of the town’s sole toy shop, a ray of light illuminates a mysterious doll. The doll’s face is stained with tears and blood; her expression, one of horror and despair.

Adelrune is strangely moved. He dares to enter the forbidden sanctum of the toy sop and question the toymaker about his strange doll. But the toymaker’s reaction is bizarre. He rages; he even raises his fist to strike the boy. The frightened child flees the man’s inexplicable anger. But it is the moment, all the same, that Adelrune has awaited: he has a quest, a purpose worthy of a knight. The doll must be rescued!

So Adelrune makes his long-planned escape from Faudace. Somewhere out there, over the hills and far away, he will find the mystical Riander. The Book has promised him. Like the knights in the stories, sacrifice, hard journeys, magic beasts, sorcerors and heroism lie ahead. But it is not until Adelrune returns to Faudace to finally fulfill his original quest that he truly understands what it is to become a knight: to reconcile both courtly ideals and fleshly temptations; honor and revenge; repentance and guilt.

These, perhaps, are the reasons the archetype of the knight has lived on into our culture, from Spenser’s Fairie Queen to TV’s Kung-Fu Knight. The Book of Knights is a worthy addition to the list. It should sit on your shelf next to Patricia A. McKillip and Robin McKinley and after Mallory’s flawed and tragic heroes.

And Monsieur Meynard, if you choose to read this — do please get the rest of your books translated into English. My French is terrible!

Copyright © 2006 by Danielle L. Parker