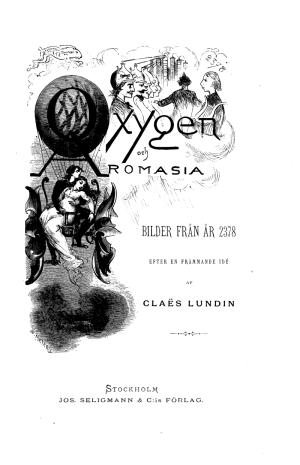

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 19 Chapter 20 appeared in issue 270. |

|

Chapter 21: Away from Earth!

part 1 of 2 |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

When Apollonides, without anyone noticing, left Aunt Vera’s evening party, he did not go the ordinary way through air. Quietly, he lowered himself down to the street and walked with uncertain steps into the district that was called the block of Hasselbacken. It was named after a refreshing institution with the same name, supposed to have been situated on the spot and have been very famous in the 20th and 21st centuries, making important contributions of the Scandinavian cultural history.

When Apollonides, without anyone noticing, left Aunt Vera’s evening party, he did not go the ordinary way through air. Quietly, he lowered himself down to the street and walked with uncertain steps into the district that was called the block of Hasselbacken. It was named after a refreshing institution with the same name, supposed to have been situated on the spot and have been very famous in the 20th and 21st centuries, making important contributions of the Scandinavian cultural history.

Apollonides entered Davidsonsgatan, one of the richest and finest business streets in Stockholm, the palaces of which were filled with shining market halls, all the way from the first floor up to the fifteenth and sixteenth rows of rooms. As usual, air cycles and other vehicles floated up and down in front of the warehouses.

The stores were illuminated in rich colors, and all the excellent products of the latest times could be bought there; and they were lined up inside the walls of kresim in artfully arranged rows that sometimes overhung the street in order to attract attention.

It was a travelling, a coming and going, a bargaining, an offering, a price-fixing, a chatting, a striving that people on the ancient business streets never could have conceived of.

”Ugh! What a noise! What a mad life!” Apollonides exclaimed, and he hastened forward to get to calmer parts of the city, but Davidsonsgatan was very long and the streets that ran into it were no less noisy.

“Why didn’t I stay in the ruins of Karlsborg!” the miserable poet complained.

This evening he was unhappier than ever, he thought. His love for Aromasia was more hopeless than ever. He had not been able to avoid noticing the artist’s coldness to Oxygen, and that had put new heart into him, spurred him to new efforts to win the love of the beautiful girl and let him see the world with more happy eyes.

But he could soon not conceal to himself that while Aromasia no longer showed the same affection for Oxygen as before, her behavior towards himself had not changed. It was still the same kindness, but a kindness without any tender feelings, without any encouragement, without signs of hope of the kindness that could be turned into affection. There was no prospect any more, not one single ray of hope. Everything seemed Apollonides to be swept into impenetrable darkness, while he groped his way in the midst of the flood of light on Davidsonsgatan.

And then he saw the picture of Oxygen again. That horrible man, who had once been his friend become his bitterest enemy. Oxygen had once tried to kill him. Apollonides was sure that it had been Oxygen’s intention that morning, when they floated above Lake Vättern and Oxygen’s vehicle decscended toward the scald’s air cycle. He did not know why the intention not had been carried out, but neither did he think very highly of it.

Had not Oxygen just this evening given Apollonides to understand that he belonged to the kind of people that were on his list for being abolished? Had the ruthless materialist not declared that it was the duty of the majority to walk over the dead bodies of the minority?

Apollonides thought he heard all this once more, and he also heard the cheers of those present and saw their scornful smiles. He had not listened to Aromasia’s disapproving words. He did not think of Miss Rosebud. He only remembered that this evening, as many other times, yes, as far back as he could remember, he had never found any encouragement but always mistrust, scorn, mockery, rejection, dislike, loathing, until these people now openly told him that he should be removed.

“Yes, it’s perhaps true. That would be the best!” the unhappy ancient scald exclaimed. “I don’t belong to the time I live in. My existence has come some hundred years too late. I should have lived in the 19th or 20th century. Then people would have understood me.”

He had just reached the block of Rosendal and bent down over the parapet of one of the aluminum bridges leading across the narrow watercourse, where the surface of the bay of Brunnsviken had once spread.

Around him and above his head, life roared cheerfully as noisy as before, on the Davidsonsgatan. He shivered at this noise. He trembled when he heard the sound of human voices.

“How happy the merciless are!” he whispered. “They don’t feel any pity for misery.”

He looked down into the water, where thousands of light from habitations on both beds and the lighting of the air-vehicles were reflected. “Shall I go to my ancestors?” Apollonides no longer whispered it but said it aloud.

“You want to go to your forefathers?” a voice was heard behind the poet.

Apollonides gave a sudden start and turned around. He saw an old man, whose dress did not seem unusual, a man who looked at him with roguish, perhaps scoffing eyes, it seemed to the poet.

He moved aside and wanted to continue, but the stranger forestalled him in a not very inviting way.

Another one who wants to scorn me, Apollonides thought, but the old man kept close to him and continued looking at him with the same strange eyes and the same roguish or elusive smile.

“Is it really your intention, young man, to go to your forefathers?” the stranger asked.

Apollonides remained silent and sped up his pace, but the stranger walked as fast and did not take his eyes off of him.

“May I ask what’s your name?” the old man said.

In wrath, the poet turned to the pushy questioner and was about to break away from the man by force, when he was surprised by the changed expression on the man’s face. It still smiled, but there was no more the taunting and scornful expression. On the contrary, there was a mild and sympathetic smile. It seemed to inspire confidence.

“Have I met a human being with mild feelings, one who feels pity for misery?” Apollonides said to himself, but the stranger seemed to understand all his thoughts and hear everything he said, even though they were not said aloud.

“My name is Apollonides,” he said aloud and stopped in order to look straight into the wonderful eyes of the old man.

“You’re not happy,” the old man said.

“Nobody understands me,” the scald burst out. “Everybody scorns me.”

“You want to die?”

“I would like to move to times that vanished long ago.”

“Yes, I heard that you wanted to find your ancestors.”

“Can you help me to do that?” Aspollonides exclaimed. He thought that when he talked about his ancestors, he had found a certain confidence in the old man’s expression.

“No, young man,” the old man replied, shook his head and smiled again.

Once more Apollonides turned away from the strange man, whose smile once more seemed abominable.

“Calm down, Apollonides,” the old man comforted. “In my odd moments I walk out and look for unhappy people in order to help them. It’s an old-fashioned profession. I know that. And I practise it only when I need some diversion.

“Most of the time I don’t have to walk far in order to find someone suffering. There’s never anyone who is afflicted with hunger, as it was in the past, but the unhappy ones are no fewer than they were in the old days. I try to comfort them, but I seldom succeed. The claim to happiness is mostly of a kind that cannot be satisfied. Even so, I do what I can.”

“You certainly seem to be a friend of humanity,” Apollonides said, and he once more approached the old man and trustfully offered him his hand.

“But a friend who cannot arrange a meeting with your ancestors. I’ve not the slightest idea of where they are now. But I know my own forefathers. I can tell you that I’m of a very old family and I’ve found out that at least the earliest branches of my family tree goes back all the way back to the Laurentian times.

“I can tell you, Mr. Apollonides, that I own a whole list of systematically arranged fossils and bones, which unquestionably have been my ancestors. For they’ve gone through all of evolution from the lowest degree of organic life to species of vertebrates and within that group up to higher forms of life.”

“It must be a beautiful collection,” Apollonides said, but he felt very little sympathy for ancestors in a petrified form.

“The collection is really valuable,” the old man uttered, “and I can show it with pride. Among the remnants of younger forefathers, I have a tooth that belonged to a marsupial, of which I’m a lineal descendant.”

“I congratulate you,” the poet said with a deep sigh.

“I have even more remarkable memories,” the stranger went on. “For example, in a kitchen midden I hit on an oyster shell with a signature inscribed by Nature itself.”

“Then what’s your name?” Apollonides asked, more in order to say something and not to be impolite to the friendly old man than because of a desire to know his name.

Proceed to Chapter 21, part 2...

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk