In the Rear View Mirror

by Bertil Falk

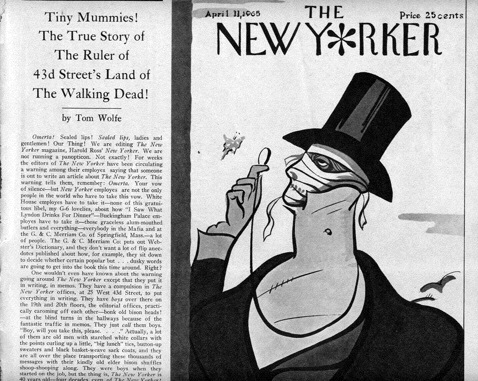

On April 11, 2008, it has been 43 years since one of the fathers of the New Journalism, Tom Wolfe, began his scathing essay on The New Yorker. It happened on April 11, 1965 in “New York,” the supplement of the Herald Tribune.

“The Walking Dead!” was what Wolfe called The New Yorker. And he appointed the editor William Shawn to be the embalmer of the corpse. The longish essay continued and was completed in a second installment the following week. The attack made great stir and caused a storm of letters to the editor.

|

What irritated Tom Wolfe was the fact that The New Yorker had the reputation of being the foremost literary periodical in the United States, both as regards fiction and essays. But, he explained, it was not The New Yorker but Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post that had published the real great writers over the years.

Wolfe: “Every so often somebody sits down and writes an affectionate summary of The New Yorker’s history, expecting the magazine’s bibliography to read like some kind of honor roll of American letters. Instead they come up with John O’Hara, John McNulty, Nancy Hale, Sally Benson, J. D. Salinger, Mary McCarthy. S. J. Perelman, James Thurber, Dorothy Parker, John Cheever, John Collier, John Updike — good, but not exactly an Olympus for the muvva tongue.”

Can you say things like that about Dorothy Parker? Perhaps. She has hardly accomplished any great literary work, but that was not her thing. What she was good at and still famous for was crushing replies, virulent one-liners, a kind of elegant and venomous jest, memorable cues.

What about James Thurber? Isn’t he a little bit immortal? And John Updike, who is still part of the game, isn’t he fitting? And lo, Tom Wolfe later on in his essay made an exception for Updike and even for Salinger, but he is careful to emphasize that Salinger was put on the market by Esquire.

Wolfe’s attack appears to be doubtful until he compares the short stories of The New Yorker with the stories that were published by Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post. Esquire published tales by Saul Bellow, Albert Camus, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Thomas Mann, John Steinbeck, many of them before they were awarded the Nobel Prize. Writers of that stamp did not jostle one another on the pages of The New Yorker.

And when it came to The Saturday Evening Post (which also paraded a cluster of Nobel Prize winners) Damon Runyon, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Alberto Moravia, Artur Miller, William Saroyan, Thomas Wolfe and Graham Greene graced its pages, to mention a few of the names Tom Wolfe dropped in 1965.

Tom Wolfe asserted that the stories published in “The New Yorker had been “the laughingstock of the New York literary community for years, but only because so few literati have really understood Shawn’s purpose. The New Yorker has published an incredible streak of stories about women in curious rural-bourgeois settings. Usually the stories are by women, and they recall their childhoods or domestic animals they have owned. Often they are by men, however, and they meditate over their wives and their little children with what used to be called ‘inchoate longings’ for something else.” Etc. The criticism, for this is criticism, boils down to what Wolfe describes as “a great lily-of-the valley vat full of what Lenin called ‘bourgeois sentimentality’.”

And Wolfe states that Shawn “knows exactly what these stories are like. He knows exactly what the literati think about them, and he doesn’t care what they think. Shawn has a more serious purpose.” And that purpose, Wolfe maintained, is preserving “the causal.” The empty faces of James Thurber’s cartoons reflects this attitude in an excellent way. Still according to Tom Wolfe.

Now, what happened. If we look back into the rear view mirror, we find that “New York,” where Tom Wolfe wrote his “obituary,” does not exist any more. It ceased to appear in 1966, just one year after Wolfe’s essay. The original Saturday Evening Post disappeared in 1969, four years after Wolfe’s essay. Esquire is still published, but rarely if at all has short stories nowadays. The Atlantic, which Tom Wolfe did not mention, has a fiction issue with short stories once every year. But The New Yorker is still around, turning out short stories on a weekly basis and on top of that has special fiction issues.

Tom Wolfe is still on the move out there. He was seen signing his books in April 2007 by one of my friends in Raleigh, North Carolina, at some kind of charity function. Still elegant, dressed in white. At the same time, in its capacity of a walking corpse, The New Yorker today must be considered to be very lively and vigorous and the ruler of the roost.

At least at one occasion, The New Yorker made a dramatic and over time influential departure from whatever editorial policy of “bourgeois sentimentality” there might have been. It was as early as on June 28, 1948, when the magazine published Shirley Jackson’s distinctive and haunting short story titled “The Lottery.” It caused violent reactions similar to those that greeted Tom Wolfe’s essay in 1965.

When Tina Brown, picked from Vanity Fair, succeeded William Shawn, the situation at The New Yorker changed in certain ways. Among other things, she let loose photographs on the pages. She was there between 1992-1998. Nowadays, The New Yorker after 2000 and 9/11 has put on a burst of speed when it comes to essays. The magazine has become somewhat of a forum for penetrating analysis and sophisticated political criticism. But that is another story.

Anyway, is there a lesson to learn when looking into the rear view mirror? One lesson is perhaps that the so-called literary establishment, whatever that is, never seemed to think that there could be good, indeed very good stories in the old pulps as well as in the pocket-sized mags. And I wonder, what does Tom Wolfe think today when he looks into the rear view mirror?

Copyright © 2008 by Bertil Falk