Willliam Morris, The Wood Beyond the World

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

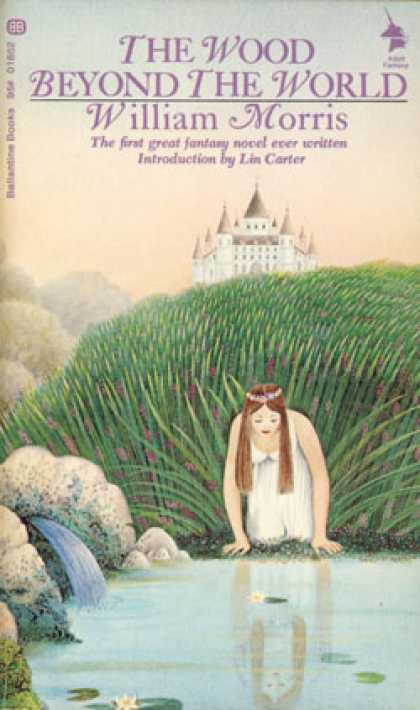

The Wood Beyond the World Publisher: Ballantine, 1974 Paperback: $12.99 Length: 237 pages ISBN: 345-23730-7-125 |

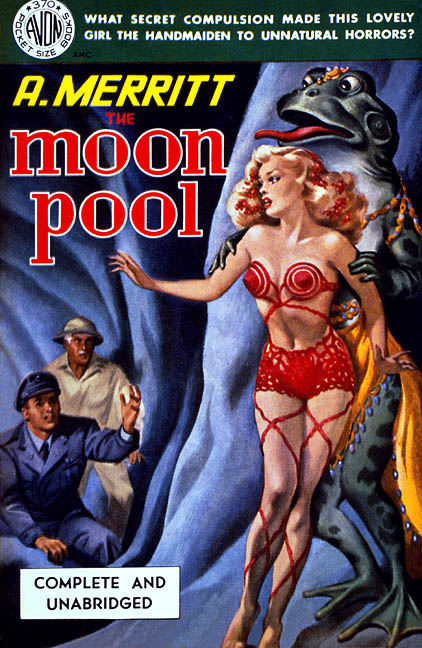

Accordingly, when I attended SPOCON, I picked up a few hoary paperbacks from one of the booksellers. The Wood Beyond the World had such a colorful fairy-tale color. I wanted an early version of The Moon Pool too, which had an equally lovely cover, but the bookseller knew to the penny how much that original paperback was worth. I was forced to settle for a much later edition featuring a naked lady (humongous rear view) in front of, naturally, a pool. In the old days, I see I could have gone without my occasional dieting resolutions.

The nakedest I could find. — Ed.

We could get nakeder, but lurid is good. — DLP |

The good news is that The Wood Beyond the World is still readable. The language is an archaic fairy-tale thee and thou, and suffers a lack of paragraph breaks to modern readers. The Wood Beyond the World was written in 1895, so Morris’ language wasn’t naturalistic to his contemporary readers, either.

But after a while I settled down to it, and the language suits the fairy tale themes perfectly. At least Morris — yes, he is that Morris, the multi-talented 19th-century designer and artist — does not belong to the wearisome yea, verily! school of King James Bible imitators (like Tolkien at his very, very worst).

And we’re all familiar with fairy tales. In this one, a young man of a good house makes a bad marriage. We’re never told why his new wife loathes this handsome, charming, well-to-do fellow (typical: he’s oblivious to his faults). But happily ever after they’re not, and being a noble fellow, young Walter mopes and pines for a change rather than setting her out on the street, divorcing her, or busting her chops. Rich Daddy owns a merchant fleet, and Walter determines to sail away from his misery aboard a ship.

But strangely he sees repeated visions of a beautiful woman, her sweet-faced maid, and a hideous dwarf servant. The three apparitions vanish almost as soon as glimpsed. Walter takes sail, and a dreadful storm blows his merchant’s ship to an unknown shore. There a hermit with a guilty conscience and evasive answers points out a mysterious pass through the mountains. Walter, afire with his visions, can’t resist.

His adventure takes him into a strange wood where he first finds the sweet and lovely maid. She is under a mysterious enthrallment, of course, by her jealous mistress. Her beauteous mistress already has a princely boy-toy in attendance, but when Walter appears, she casts her eye on him (and pretty soon, her clothes get cast aside, too).

Things get complicated, for though Walter has (in the best tradition of courtly love) pledged his troth to the sweet maid, he’s got an eye for her mistress, too. The boy-toy Prince is suffering the same urge to try greener grasses. All the while, around go the ugly dwarves, yelling mysterious warnings and threats against maid and suitor both.

Both the mistress and her maid are enchanters, and I was sure this book was going to turn into some kind of Triple Goddess deal (maybe missing the crone), where the maid was actually the mistress, and the mistress the maid, somehow. The roaring dwarfs I assumed to be Circe-like victims and former boy-toys in real bad humors.

But no: all the elements are there, dragging the reader on in real fascination, and then it’s as if Morris lost his nerve. He tacks on a familiar fairy-tale happy-ever-after ending, and leaves me scratching my head on what the relationship between maid and mistress ever really was. And how about the bad wife left behind? Walter takes up with his sweet maid, and Morris forgets about the bigamy problem. Guess divorce was a problem in those days.

The last book I reviewed (Consider Phlebus) had a sudden bad end, and this one had a sudden good end. They should have swapped. I had fantasies of re-writing this fairy tale with the story I was sure Morris really had in mind. You might find it a fun exercise, too. Have fun! And you can find the entire text free on Project Gutenberg. Even better.

Copyright © 2009 by Danielle L. Parker