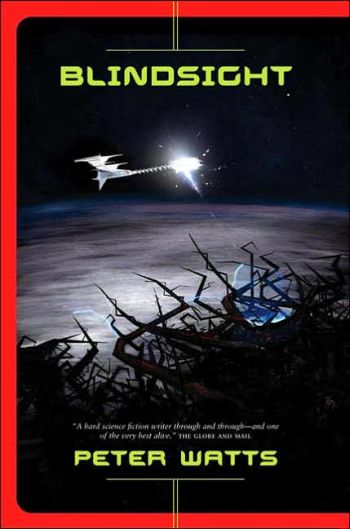

Peter Watts, Blindsight

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

Blindsight Publisher: Tom Doherty, 2006 Length: 374 pages ISBN: 978-0-7653-1964-7 |

But when a book’s about ideas, you’ve got to talk about the ideas in the review. So sorry, Mr. Watts. 374 pages for you, and one for me. So if I miss a few notes, fumble a few points, you can forgive me.

Blindsight belongs to the venerable science fiction genre of First Contact stories. One evening, alien machines visit the Earth and snap-shot the entire planet from orbit. Then they self-destruct before anyone can inspect them, but Earth soon learns a message has gone out to someone... or something. When the transmitter is discovered and found to be a decoy, Earth sends out an investigative team to track down the real aliens.

It’s slow going before the showdown, because there’s no magic faster-than-light in this future. The team gets a splice of vampire gene and a predatory vampire captain to help them survive their years-long cold sleep, and when they wake up, they’re face-to-face with a mysterious solo gas giant. The aliens are headed our way, and the team has to figure out what they are, what they want, and maybe save Earth.

That’s the classically simple premise, but this is far from a simple book. Blindsight was nearly too freighted with ideas to wade through at times. But like the best science fiction, the mirror Watts holds up is focused on humanity as much as it is on the alien.

I give the author credit for taking on some unusually daring questions in his work. Some of his questions include What is the nature of consciousness? and, more important, What is its value? Is self-awareness a survival trait, or is it an evolutionary dead-end? If we meet intelligent aliens, will they think? Will they be something completely different from our own self-aware, gene and DNA-based model?

Throughout the book the author tinkers with the whole concept of mind and self-awareness. The protagonist of the story, Siri Keeton, has a surgically-damaged brain which precludes him from understanding his fellow humans in the normal sense. The vampire captain is an utterly cold, cannibalistic predator and savant. The linguist has split her brain into four (or more) personas. Bates, the military expert, spreads her consciousness thin to control her robotic soldiers. Another scientist on the team has rewired his entire sensory circuitry so he can taste what he sees, feel what he hears.

Then there’s the protagonist’s smothering mother, who downloads herself into a virtual Heaven; and his girlfriend, who insists on experiencing life in the polar opposite of touch-my-sweaty-flesh (but can’t resist tinkering with her boyfriend’s mind, either). And the aliens, in turn, play various hallucinatory and tricksy mind games with the investigative team.

An untouched frontier of science even in our day is an understanding of the true nature of consciousness. How we form subjective self-awareness is too elusive to fully grasp. The mind seems more than the sum of its physical parts.

But every day now, we’re poking the brain with a stick. The author points out in his notes that:

“Sony has already patented a machine that uses ultrasonics to implant ‘sensory experiences’ directly in the brain. They’re calling it an entertainment device with massive applications for future gaming. Uh-huh. And if you can place sights and sounds into someone’s head from a distance, why not plant political beliefs and the irresistible desire for a certain brand of beer while you’re at it?”

Are you getting queasy yet?

In the modern day we look at science and religion as two polar opposites with nothing in common. Mutual scorn rules.

But science operating without moral and ethical constraints may be a more frightening scenario for the future than the past sins of faith. It’s not enough to say “in the name of pure science” or “We do it because we can.” Religion exists for many reasons, and attempts to figure out what we should do or what we shouldn’t do for our own good are two of the better reasons.

We brought to life the atomic bomb, nerve gas, and heroin in the name of scientific investigation. Where do we go next? I can’t help but hope a lot of scientists are on their knees praying to some kind of Deity that what we do in the future in the name of scientific advancement won’t be worse than what we’ve already done to ourselves. Sony, are you listening?

Copyright © 2009 by Danielle L. Parker