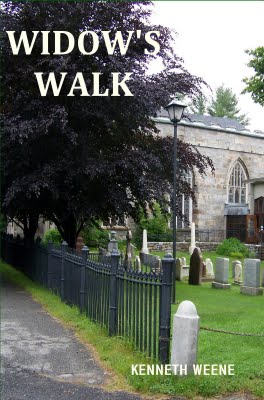

]. Kenneth Weene, Widow’s Walk

excerpt

Widow’s Walk Publisher: All Things That Matter Press (August 2009) Length: 220 pp. ISBN: 0984098429 978-0984098422 |

In all her years of faithful attendance, Mary has never before been in the rectory of Saint Margaret’s. It isn’t that she has never been invited. Indeed, Father Frank has often suggested that she stop by for a cup of tea. It has been, rather, an integral part of her self-negation. How could she possibly intrude on the fathers or even on Mrs. Walsh, their housekeeper?

Today, however, is different. As she had knelt in the confessional, Mary had fainted. Father Frank, hearing the soft thud of her body hitting the floor, had rushed from his compartment into the penitent’s and gathered Mary in his arms. He had been surprised by her lightness as he hurriedly carried her across the courtyard and, kicking at the door to get Mrs. Walsh’s attention, brought her into the parlor and laid her on the red-brocade couch.

Mary awakens. The priest and housekeeper are both hovering over her. A capsule of ammonia has been broken under her nose, and her eyes are tearing. She can feel the reflexive gagging and tries to control it.

“Get some tea, Mrs. Walsh,” Father Frank commands.

“Yes, Father. Oh, Mrs. Flanagan, are you all right?”

“What? Yes. I don’t know.” The words stagger out.

“The tea, Mrs. Walsh.” The anxiety in his mind mocks the command in his voice.

“Yes, Father.” The housekeeper, all-aflutter and confusion, scurries from the room, trots into the kitchen, and sets the kettle on the stove. “Oh my,” she mutters. “My, oh my.” It is not the first time a parishioner has fainted, but each time Mrs. Walsh has been overwhelmed. She takes personal responsibility for the smooth running of the rectory, and any disturbance is more than she can accept — it is as if some evil force has dragged dirt and disarray into her carefully cleaned and ordered world.

That evening Mrs. Walsh will once again offer her resignation. She has done so whenever one of the priests has had to speak to her twice. Of course, the offer will be refused, and she will be reminded how valuable a member of the team she is. The priest will ask who else could make such delicious meals or keep the large, old rectory so spotless.

In her way Frannie Walsh relishes these periodic offers to resign. They reassure her of her great worth. But, when they are made, they are made in an earnest sense of her shortcomings. Although they barely know one another, Frannie Walsh and Mary Flanagan are sisters-under-the-skin — sisters in the harsh faith of their upbringing and sisters in their determination to maintain order and cleanliness in a world given to the terror of disarray.

Mary looks around at the ornate rectory parlor. It was furnished at the turn of the twentieth century, yet every item is still in perfect condition. The silver candlesticks on the mantle shine from Mrs. Walsh’s almost daily polishing. The oriental carpet is a deep wine red with intricate designs in blues and gold. The couch on which she lies and the chairs in the room are all stiff and straight backed. She wonders if the priests sit at attention while saying their evening prayers.

“We don’t use this parlor very much.” It is as if Father Frank has read her mind. “There’s a much more comfortable room where we can lounge and watch television.”

That information at once reassures and frightens Mary. She wonders why she has been brought into this formal parlor. Surely she has broken a serious rule. She knows that she will have to say an extra penance for it. “How did I get here?”

“I carried you from the church. You’re not very heavy.” For the priest to have carried her — now that surely was a sin on her soul.

“Frannie,” he calls in a voice that is not so loud as it is imposing, “Where’s that tea?” Then more softly, “I think you’d better eat something and have a cup of tea before you try to get up. Would you like me to call the doctor?”

“No, no, I’m feeling fine now. I can’t imagine what happened. I remember starting my confession, but I don’t remember anything else.”

“No, I don’t imagine you do. You must have fallen forward in a dead faint. I heard you hit the floor and came in to find you crumpled up. Have you been ill?”

“Ill, no. It’s only...” The enormity of her emotions suddenly breaks through. Mary starts to sob. She can barely breathe with the heaving of her breast and the tears clogging her nose and dripping down into her throat. She has never cried this way in her life. Never, not when she had learned of her parents’ deaths, not when Sean had died at the wheel of his bus, not when Seany had come home more helpless than he had been born, not when her daughter had lost the baby and her womb, certainly not when Lois had announced her leaving. She has shed few tears since she had come to America. Her strength, rooted as it is in her deep faith, doesn’t allow tears. Indeed, the few times that she has cried over the years have been confessed as times when she has doubted God’s grace and Christ’s love. Now, however, Mary Flanagan is sobbing with an intensity that makes the compassionate parish priest step back and clasp his hands in dismay.

It is at least fifteen minutes before Mary has stopped sobbing — before she has caught her breath and is able to eat a bit of carefully-buttered toast and drink some of Mrs. Walsh’s strong tea laced with the fathers’ best brandy. Her face is deep red, and her eyes are even redder. Her nose is still stuffy so the priest gets her a tissue, which, having used, she tucks neatly under the cuff of her blouse. The orderliness of her soul is beginning to reassert itself. She unconsciously fusses at the hair over her ears. “I’m so sorry, Father. I’ve been such a silly bother.”

“Mary, you have a right. This is your parish. We’re here for you. In all these years I’ve wondered how you’ve stayed so strong. You’re entitled to cry. We all have bad times.”

May cannot help but protest. “Not compared to the Holy Mother, not compared to Our Lord. We don’t have...”

“Mary, we’re human, not divine. We have human frailties. Don’t you think God understands that? He created us. He cares about us. He suffered for us. Surely, He also understands us.”

Mary Flanagan snuffles one last time. “Thank you, Father. You’re right of course. It’s just — it’s my son. He’s leaving me, and I don’t know what to do. I know it’s selfish, but I’ll be all alone if he leaves.” She pulls the letter to Sean from her pocketbook. “Father, what should I do?”

Father Frank reads the letter carefully and then again. “You must let him go,” he says with as much concern and comfort as he can give. “If Sean can have a more normal life, if they can help him, you must let him go.”

“I know that, but what should I do?” This time she stresses the “I”, and the priest understands the total emptiness of Mary Flanagan’s life.

“Without service, without responsibility: how can she go on?” he wonders. He knows many women like Mary, like Fannie Walsh, like most of his parishioners — women whose lives are all about duty never about self.

On one wall of the parlor there is a mahogany bookcase with glass doors. Decorating the doors are filigrees of mahogany. The shelves of the bookcase are filled with books bound in beautiful red leather with real gilded lettering on the covers. The books and bookcase are collectors’ items. Nobody ever opens the doors or reads the books. Indeed, as most are written in Latin, younger priests would have a difficult time making much headway in them.

Father Frank looks at the bookcase with its precious yet in some way meaningless books. He thinks of the value men put on such external things never thinking about their inner value. “How strange,” he thinks, “this woman has such great inner value and none on the surface and over there is so much external value and none within.”

He offers the only help he can, the advice that Mary has come to hear. “Let us kneel down and pray to God for guidance.”

The three of them kneel: Mary, the priest, the housekeeper. “God we ask your guidance for this woman. She has to find direction in her life. She has served you faithfully these years, and now she is as Jonah, tossed on the sea of life. Help her, we pray in Your Son’s name.”

The three kneel on the wine red oriental carpet in front of the stiff backed sofa and they pray. They pray silently for an hour. One thought runs through Mary’s mind like the refrain of some long lost song, “Mother of God, I need to know. Mother of God, I need to know.” She is not sure what it is that she needs to know nor how The Holy Virgin will answer her.

Suddenly, without understanding why, Mary changes the cadence of the words which have become a mantra. The emphasis changes from “Mother of God” to I. “I need to know,” iterates Mary. “I need to know!”

It is then that Mary crosses herself and silently says, “Thank you, God.” She quietly rises, puts the letter, which has been lying on the sofa, back into her handbag, and leaves. She walks out the front door of the rectory with her head held high, knowing that she had every right to have been there. She walks out of the rectory also aware that she has changed and that her life will be taking a new road.

When Mary gets home Sean says, “I was worried about you, momma. Where did you go?”

“To talk with God. Where else would I go?” Unconsciously, she reaches up, removes her glasses, cleans the lenses and pushes them back on her nose. Then she slips her hands under the feathers of her hair and fluffs it.

“I hope He heard you,” says Jem, who has stayed with Sean while Mary has been out.

“So do I.” Mary pauses. “No, I’m sure He and The Blessed Virgin both heard. They hear everything. I just don’t know how They’ll answer.” She pauses again. “But answer They will — that I know.”

Copyright © 2011 by ]. Kenneth Weene