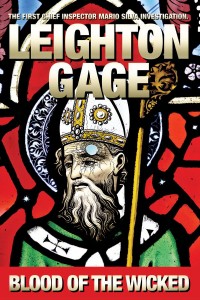

Leighton Gage, Blood of the Wicked:

a Chief Inspector Mario Silva Investigation

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

Blood of the Wicked Publisher: Soho Press, 2009 Length: 322 pages ISBN: 978-1-56947-470-9 |

Since I’m preparing to write a third Minuet James novel to be set in Brazil, I’ve worked hard trying to find what English-language translations I can. The poet Paulo Leminsky, a Portuguese-language e. e. cummings, has been one sly and fun surprise. Then Mr. Gage’s rare police procedural, Blood of the Wicked, turned out up at my local library.

The Scandinavians are known for gloomy police procedurals. Brazil, on the other hand, is a country known for a spirit of optimism (or is it denial?) even in the face of notorious social problems. I must say that summarizes Mr. Gage’s novel. We have worse social problems in this book than any gloomy Swede cop ever dreamed of, and yet — in the end — justice is done and his Brazilian counterpart goes home with a smile. I’ve never read a book so simultaneously hopeful and yet downright alarming.

Mario Silva starts on a life of the law in the same contradictory spirit. He burns for justice for his casually murdered father and the mother he lost in the same incident (a mother who first had to suffer rape). He can’t get justice, or even interest, from the police, so he becomes a policeman himself. In the end, he doesn’t even try to go the official route. He knows it’s no use. So he’s forced to dispense Dirty Harry style justice on the perpetrator with his own hands.

His early story parallels his current investigation, a tale of justice done in the end, but not by officialdom. A newly appointed bishop arriving to dedicate a new church in framing and agricultural town in western Sao Paulo state is shot as soon as he steps out of his helicopter. Silva is sent to investigate the politically charged case.

When he arrives in Cascatus do Pontol, more crimes fall into his lap. The local agitator for land reform, along with his wife and children, has just been horrifically assassinated by men in hoods. Silva discovers a string of street children killings that the insolent and on-the-take local police chief never bothered to report. The priest in charge of the new church wears sickening lilac-scented cologne, and casts insinuation on his fellow priest, a liberation theology supporter. The local landowners have hired guns from out of town and are breathing fire. Soon, the tough-but-not-tough enough local newswoman and her lesbian partner are found with throats slit, too.

Silva’s boss is screaming down the phone at him, and given the rash of killings that soon follows all of the above, his director’s bad mood is quite understandable.

Silva soon gets the picture, but just as in his personal past, finds he can’t do much in terms of official justice. Money, power politics, hired muscle and entrenched class divides tie his hands. Once again, individuals are forced to dispense justice since the state can’t do it. It’s cheering to see the bad guys bite the dust... but sobering that, in this Brazil, no vested authorities of law-and-order are able to execute that justice. Not many individuals have the capacity, or the means, of dispensing such violent justice themselves. We’re left wondering how many of the bad guys must get away in real life.

Gage’s book is a solid if somewhat slow-starting police procedural set in a society we don’t get the change to read about as often as we should. Check it out.

Copyright © 2011 by Danielle L. Parker