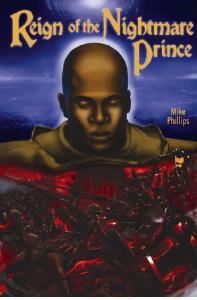

Michael Phillips, Reign of the Nightmare Prince

excerpt

Reign of the Nightmare Prince Publisher: Journalstone, July 8, 2011 Categories: young adult, fantasy, science fiction

Length: 262 pp.Price: $12.95 U.S. ISBN: 9781-936564-11-8 LCCN: 2011931053 |

The crusade against the invaders leads to battles against not only the mystic and evil terrors native to Rakam’s world, but also with the alien powers that wish to destroy everything. Survival means defeating an enemy with superior weapons and a thirst for blood. Although it seems like a fight he’s destined to lose, Rakam is willing to die to save his world from certain annihilation.

Chapter 1

Though his people were down at the village circle, dancing in celebration round a fire as tall as a man, the Chief felt ill at ease. Not long ago, just as he and his sons returned to the village with meat for the feast, he was troubled by an evil presence. Sitting in the doorway of his hut, he wondered now if he should have ignored the feeling. Of all times this was the most dangerous. The Long Night had come.

“Are you coming, grandfather?” the Chief’s grandson Kitpa asked in his small voice, fingering the ceremonial mask sitting proudly on his dark head.

The carved and painted likeness was of some terrible beast from the land of spirits, with features grotesque as only nightmares can make them. The mask had once been his, and he remembered wearing it with similar pride, a sign he was becoming a man. The memory made him smile, gifting him with a momentary distraction from his troubles.

“Grandma is looking for you.”

Much annoyed, the Chief said, “Tell your grandmother I’ll come when I’m ready, sometime before all the water has fallen from the sky and the lake has dried to its bottom.”

The boy said nothing, not knowing what he should do next. He bit his lip, fighting off tears, thinking he had failed in his errand.

The Chief was touched with sympathy for the child, set between such terrible adversaries as he and his beloved wife. Inspecting the mask with approval, he gave Kitpa a wink and a smile. “You’ve done well and earned a fine reward for your trouble. Tell your grandmother I promised you some of her best candied fruit. She can’t keep it all to herself. She’s already too sweet by half.”

The boy grinned.

Swatting his grandson affectionately on the bottom, the Chief said, “Now get! I’ll see you in a little while. Have fun and stop worrying about an old man.”

Released from his errand, the boy hustled off with both hands on the mask, careful not to let it fall. In the distance, drums started beating, crafting magicks of protection for the village and its people.

“Be safe, dear child,” the Chief whispered, “May the darkness work no evil upon you or this place in the Long Night.”

Yet, the prayer gave him no comfort. Turning away from the village circle, he looked toward the lake, searching for some omen or sign. What little celestial light that blessed the land revealed nothing. He tried to tell himself it was an old man’s imagination that was the cause of his fright, not some real threat. But he knew better. It had been real. It had been out there.

Earlier, when he and his sons were returning to the village with meat for the feast, his son Pakkea had felt it, too. “What care is it that wilds your mind?” the Chief had asked.

“Nothing, most honored father,” Pakkea replied hesitantly. “I thought I heard a noise, that’s all.”

“Hatcha ate too many beans,” Saska, the eldest son, joked.

Hatcha replied with an ill-tempered grunt.

“It gave me a strange feeling, but it’s gone now, whatever it was.” Pakkea made a laugh that held no mirth. “The Long Night will have me jumping at water beetles if I let it.”

Hatcha said, “If you’re done acting like a little girl, can we go? My belly aches like a katabo.”

“Go on. Mamma wanted me to bring back some good reeds if my arms weren’t filled with game.”

“You’ll spoil that wife of yours,” Hatcha said.

“When you get a wife of your own, I might take your advice.”

The rebuke was met with approval from his brothers. Even so, Pakkea did not relax as he handed his portion of the kill to his younger brother and set to work collecting reeds.

As he and the others departed, the Chief called over his shoulder, “Don’t be too long.”

Through the entire exchange the Chief had remained silent, and as he watched his people gathering for the feast, he thought about his own feeling of apprehension. He had felt something too, but had no better explanation for it than his son did. The thing, whatever it had been, had robbed him of his courage. Thinking on it, his mind turned again to the Shaitani and to the stories his grandfather told about the pale skinned, savage beasts that swept from the mountains like hunting packs. They destroyed villages, taking people away, never to be seen or heard from again.

It was said the Shaitani used children in the practice of their dark arts, that by hot blood or a still beating heart they could gain mastery over the forces of the cosmos. Many good warriors his age said such ideas were nonsense, stories to scare children into behaving well when the darkness came and danger closed in around them. But the Chief knew differently. If his grandfather said that such a thing was true, then it was true. He needed no more proof.

The drums quickened. Soon the ceremony would begin. The Chief leaned back on his elbows, staring deeply into the night sky. A new star shined in the heavens, lonely, as the clouds thickened and the consuming darkness seemed to press in all around him. Never before had he seen such a thing, a star beneath the clouds, so low in the sky that a man might pierce it with a well aimed spear. He wondered if this too were a vision, an omen sent by the Almighty to warn the faithful of coming danger.

“You’re as big a fool as Mamma always said,” he pronounced with conviction, slapping his flanks and rubbing the stiffness from his joints.

The Chief shivered. His skin pricked as with a hundred insects, a feeling as if he were being singled out as prey. He gripped his spear and stepped back into the night shades cast by the hut, standing very still, listening and waiting. Shadows gathered between him and the fire, slipping unnoticed in and out of huts, sliding round people and trees, mixing with the harried light stirred by dancers and the flickering flames.

“Honored Chief,” a brusque voice called out, nearly startling him.

It was the Kasisi, the holy man of the tribe.

“Please join us at the fire,” he said. “All is ready. They will want their Chief to give his blessing.”

“Yes, yes, thank you, Jakma. I was just on my way.”

“Is everything all right?”

The Chief had never much cared for this man, done up in a fearful mask he had no business wearing. His father had been a fine councilor and a good friend, but he had died young. Perhaps if his son had had the benefit of a more lengthy apprenticeship, his arts would be sharper.

“No,” the Chief said, “just an old man at the coming of the Long Night.”

The Chief looked up, about to point out the strange light he had seen above, but it was gone. Perhaps it had never been there. The shadows must have been just a trick of the firelight. Maybe he was getting old and his mind was indeed growing feeble.

“Tell me, Jakma, do the stars shine favorably upon us?”

“All is right in the heavens. We are truly blessed.”

“Good. Thank you. Tell Mamma I’m coming. She has no need to send others to fetch me.”

* * *

Down by the fire, the people danced. Crafting the ancient forms of the great beasts of the wild, they bared teeth and curled fingers into claws. As the drummers beat a fierce rhythm, they paced and circled, finding a victim amongst the crowd. First one child and then another was chosen, singled out and attacked. The children ran in horror and delight, screaming and laughing as they were chased down and made into a meal.

The Chief laughed as he saw them. The real dance had yet to begin, the ceremony that would give his village the much needed protection through this dangerous time. This was much more fun to watch. He remembered being chased as a child and in his turn chasing his own children. Halfway to the village circle, he stopped short.

Pakkea paced the outer ring of the fire, body tense, looking as though he truly intended to take a child as feast. The children sensed his mood, and they backed away, afraid some spirit of the forest possessed their playmate. Smiling in a kindly way, Pakkea sent them back to their parents. He paused to speak to his brother for only a moment before stalking off toward the village.

“What is it, my son?” the Chief asked, touching the handle of his knife. He was carrying his Chief’s mask for the ceremony, but also had a bow and a quiver of arrows slung over his shoulder.

“Nothing, father. Mamma sent me after a knife,” he replied, but the excuse didn’t hold true.

“The Long Night comes and many sorrows trouble the world,” the Chief assured him. “Tell me.”

Glancing into the darkness, Pakkea began, “It was the same as it had been at the lake. I heard a noise where none should be, felt like some peril lay hidden from me, some cloud covering my eyes. Hatcha was sitting nearby with his friends, but he was in more of a mood to taunt me than to look for danger.”

Nodding his head toward the fire, the Chief said, “And did you see anything?”

“There was a place in the dirt where a large stone had moved. A footprint was nearby, the like of which reminded me more of the cloven hoof of some beast of burden than a man.”

As they began walking toward the village, shadows swam upon the ground like serpents on the lake. Dark and foreboding, the trees swayed above them with the blowing of the wind, the ghost shapes of the leaves and branches working the complex patterns of destiny at their feet. But the shapes were strange, alive with purpose.

Something hard and cold brushed the Chief. He looked over his shoulder to see what it was, but nothing was there. Pakkea watched his father turn and reacted in kind. Saying nothing, he pointed to a dark patch on the ground and gave his father a fearful look. Ethereal, like a cloud shadow in high sun, it moved away, in a direction against the wind. The Chief set a hard look to his features and nodded agreement.

“Attack! Attack!” the Chief shouted, dropping the mask and putting an arrow to the bowstring, searching for the prospect of a target.

As if in reply, the nearest hut burst into flame. Wood and thatch caught quickly, the fire spreading with unnatural ferocity. The feral blaze gave rise to a cloud of smoke that fouled the air. Thick and putrid, the stinking smoke swallowed everything around it, clinging to the ground like the sky-form of some beast from the underworld.

Choking from the smoke and sudden stench, the Chief and his son bent over clutching their stomachs. Nearby, balls of flame leaped from what seemed the shadow’s place. The Chief pointed, disbelieving what he saw. Stories told of the ability of the great Kasisi of distant lands to control fire, but he had never before heard a tale of such power as he was witnessing now.

“Run!” the Chief shouted.

“I’ll not leave you.”

“Your family.”

“Take my hand.”

Together they ran to the village circle. Behind them the huts lit with fire as bright as dawn. Women were screaming. Children were crying out. But the warriors were making ready. They stood between the village and their families, holding whatever weapons could be gathered in haste.

“Do you see them? Where are they?” the Chief called out.

“No,” replied Saska. “We’ve seen nothing but the fires and our Chief coming to lead us.”

“More like running for my life,” said the Chief under his breath. Louder, he said, “Everyone get down. Take cover.”

Surprised to find that none were harmed, he pointed to a group of warriors and said, “Get ready. The others must stay. Pakkea, that means you.”

“But father,” Pakkea protested.

“Stop! Keep the children safe. There is no greater price among all the fortunes and glories of war.”

Pakkea nodded, ready to do what was commanded.

“Listen to me, all of you. There is some devilry at work here. The Shaitani have returned. There is a sorcerer amongst them. They have a great talent in working fire. We have nothing to make our defense but our hands and our lives, but fight them we must. They also have some trick, making themselves invisible, so be on your guard. They could be anywhere. Look for shadows upon the ground.”

Quickly ordering themselves for battle, the warriors marched toward the village. Huts were burning, but there was no sign of the enemy.

“Where are they?” Hatcha growled. “Why don’t the cowards fight?”

“I don’t know,” said the Chief.

“Maybe the fire is a curse brought down on us from the sky,” someone said in a weak voice, scared and pitiful. The Chief thought it sounded like Jakma.

“No, Pakkea and I saw it happen.”

Saska said, “Then where are they?”

“I don’t know.”

A moment or two longer, the Chief made a decision. “This is a night for death. Let’s search the village. We must bring the havoc of battle on our own terms.”

Silently the warriors gathered in formation, marching toward the still burning huts, the light of the flame hot and fierce. The air was thick with smoke, mixed with an odor beyond their knowledge, the remains of some witchcraft, perhaps.

A stiff wind blew and the fire crackled, sparks like dragon spawn into the night. The steps of the warriors were heavy upon the ground as they approached their burning homes. With a flash of light, something appeared.

The creature was tall and broad, standing upon two legs, but looking very little like a man. It was black as night, with a shining carapace like the dung beetles women coveted so much as jewelry. The Chief thought bitterly that the Shaitani would be much prettier if it too were strung upon a cord around his wife’s neck.

The Shaitani had no features, no ears or mouth or even hair, save two darker slits where eyes should have been. Those black slits seemed pitiless, cruel, and they held a cold menace the Chief had never felt before. The Shaitani just stood there, facing them, its hands loosely cradling what looked to be a long club of some kind, waiting patiently as the village was consumed behind it.

The Chief signaled his men to stop. Well trained in the arts of war, they went into a defensive posture. Reaching slowly into his quiver, the Chief’s fingers played across the many arrows with points of bone until he found one of the metal tipped shafts that were the prize of his youthful journeys upriver. Those points had ever been his treasure, awesome weapons that cut deeply into the flesh of even the most formidable game. Two were all that was left of the score he had once possessed. The others he had given to his sons or lost to misfortune. If any weapon in his possession would penetrate that shell, these were it. Hand shaking, he withdrew the arrows. Holding one in reserve, he set the other to the string and waited.

At some unknowable signal, two more Shaitani appeared. They were big, as strong and terrible looking as the first. The one on the left was banded with stripes of yellow and black, while the other was red as blood.

Thinking it time to make a show of strength the Chief stood, his warriors rising beside him. He readied the bow and called out the ancient curse to all the enemies of free people. With that, he and his warriors stomped and clapped and raised a battle song to the Almighty, preparing themselves for war and their enemies for certain death.

In rage and defiance, he let his arrow fly. Seeing the flash of metal, his people cheered, knowing what a mighty weapon their Chief had loosed upon the enemy. The arrow streaked through the air straight and true as a star in flight across the heavens. It struck the black Shaitani in the chest. The villagers whooped in delight, but as the arrow hit the shining carapace it snapped, shattering in pieces, falling without effect to the ground. The villagers went silent.

A line of Shaitani stepped from the shadows. They shined dully in the light of the fire. Their very skins seemed to be made of metal akin to the Chief’s prized arrowheads, strange symbols of some evil enchantment written upon their bodies. The line of Shaitani stretched from the village to within a few paces of where the women and children huddled together. Between the Shaitani and the fire, they were surrounded.

The Chief swallowed hard, doing his best to steady his voice. They had no defense against so great an enemy, but he hoped that perhaps a few of them could survive if he had courage to do what a Chief must.

“Pull them apart like bugs. That will be their weakness.” The Chief’s word was passed among them. “When the battle comes, Pakkea and those with young families must provide for the escape of the women and children.”

“Yes, my honored father,” said Pakkea in return.

“Take them deep into the forest, spread out. That is your only hope. We will fight them as long as strength remains in our bodies.”

“But where are we to go? Where will we be safe?”

“Courage, my son,” the Chief said, putting an affectionate hand to Pakkea’s shoulder. He looked deep into his eyes as if to remember him always. “Find your way to Pakali; but go in secret; the Shaitani will know the paths and will search the river.”

“To the Marsh King?”

“Yes.”

“But it’s so far away.”

“None of the villages have strength enough to challenge this threat. Warn them if you can.”

“Yes, father.”

They embraced.

“Hurry now, be ready. May luck and the Almighty be with you.”

Pakkea began to spread the word. Those men with young families nodded sullenly and collected what they could for protection, if only a rock or a burning stick to add to their ceremonial accoutrements. Those men with sons of a suitable age gave instructions and then ordered themselves near their Chief.

When all was ready the Chief said, “Now, we will attack first. Split into two groups. Saska will take the left side, and I will lead the right.”

A queer sort of horn blew, a sound harsh and piercing. The red Shaitani raised his club into the air and shouted. The stick made a crack like thunder and spewed a brilliant flash into the night sky.

The Shaitani army held their clubs out in front of them. The horn sounded again, and the weapons flashed and cracked. Many warriors fell to the ground, struck dead or clutching bloody wounds. The women screamed and the children cried at this new horror. With a last note from the terrible horn, the Shaitani charged. The Chief shouted the call for battle, and they rushed to meet the attack.

Copyright © 2011 by Michael Phillips