Beverly Forehand, Haunted Homeplace

excerpt

Wake the Dead

Haunted Homeplace Publisher: 23 House, Sept. 8, 2014 Length: 238 pp. ISBN: 1939306019; 978-1939306012 |

“Then away out in the woods I heard that kind of a sound that a ghost makes when it wants to tell about something that’s on its mind and can’t make itself understood, and so can’t rest easy in its grave, and has to go about that way every night grieving.” — Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Prosper Vance was not a young man. But he wasn’t an old one either. He’d sat as sheriff for the County for forty long years coming straight off of a hitch with the Army. He’d put down one gun and taken up another and a cause along with it though he didn’t suppose he’d known that at the time. He’d sworn with his hand on a Bible to protect and serve, and, he reckoned, he’d done his best. He hadn’t realized all those years ago, just what service really entailed. That he had given up a piece of his life and maybe a bit of his soul to the folks in the County. That boy of forty years ago may’ve understood he was signing on for long days and sleepless nights, but there was no way he could’ve fathomed how dark men’s hearts could be or how the sight of a gold band laying on your palm could fill you with a cold despair for which there were no words.

Prosper thought about that boy sometimes and he wondered if he would’ve made the long drive to the Old Man Everett place or if he would’ve dared to ask for so dark a favor. Prosper was not a church-going man, but he believed in God all the same. He’d sat with his Mama and brothers through a childhood of tent revivals and Sunday sermons. He knew for a fact that Heaven and Hell were as real as the lines on his face though he often thought they existed as much in the here and now as in the hereafter. He couldn’t imagine there were devils any worse than the black-hearted men who walked among us or angels kinder than folks he’d seen forgive time and time again those that did them wrongs so great that Prosper had to steel his own heart not to take a vengeance for them.

A sheriff’s badge was a heavy thing. It bound the man to the law whether that law was just or not. Prosper reckoned that there were some who just didn’t deserve to walk this green earth. But that was not his decision to make. He’d taken up his burden and bound it to his chest. And, after forty years, they were as wed as any for better or for worse.

There was no reason, really, to have doubted the facts of this case. They were hard and cold and clean. Amy Green was dead. Plain and simple. There was no need to call it murder, and yet murder, Prosper believed, it was. It pricked at him. That was it in the end. He had no proof and no reason to doubt the coroner’s words or his own eyes, but there it was. Even after the case was closed and Amy safely put to rest, Prosper could not let it be. He read his case notes each night and he found that any walk he started would take him past Amy Green’s house with its white-washed fence and little tire swing. He saw her widowed husband walking their puppy, a dog Prosper had seen the girl playing with on the town green not a month before, and it caught at the edges of his mind. In the end, the only reasoning he had was the simplest arithmetic — it just didn’t add up. A happy girl, just married, with the sold sign still on her new lawn and a bright pup in the yard does not walk out into Silver Pond and drown. She just doesn’t.

Amy Green had a common, happy life. It was not the stuff of stories. It was the welt and waft of reality. She worked at the bank, she walked her dog, she shopped at the local Piggly Wiggly on Thursdays, and she was happy. She was happy. Any fool could see it. But one night she had laid her wedding ring on the kitchen table, locked the doors behind her, and walked barefooted down the long gravel drive and then down the Interstate Road. She’d climbed the split rail fence surrounding the Hayborne pasture and walked straight into the pond. She kept walking til she was at the center where her feet couldn’t touch the ground and then she’d let go sinking into the goose grass and mud. If she had any final words, only the frogs and catfish heard them.

Her husband found her ring on the kitchen table, the car in the drive, and Amy gone the next day and raised the alarm. Even though only a few hours had passed, Prosper and his deputies started their search. Amy was not the kind of girl to leave in a huff. She was a careful woman, a bank teller and a regular member of the Clearmont Primitive Baptist. She volunteered at the community center once a month when local relief passed out necessities to those who needed them, carefully sorting out bags of floor and rice, boxes of cheese, and cans of beans and putting them in cardboard boxes for the folks who would come by throughout the day.

It was Prosper’s newest deputy, Michael Allen who found her floating in the pond, her long black hair tangling with the weeds. When Prosper arrived at the scene, the boy was weeping, but, as he’d been taught, he’d left the body as it was found, though you could tell it pained him. The coroner confirmed what Prosper’s own eyes could see — there wasn’t a mark on her other than her bloodied feet. She had simply walked into the water and let go. She left no note, only the ring and a fresh bowl of food and water for the pup. There was simply no call for it, and, after forty years of suicides, homicides, robberies, and lies, Prosper knew the smell of a case that just didn’t add up.

He didn’t mean to take the ring. It should’ve been given back to Amy’s husband or slipped on her hand in the casket. But the bereaved man didn’t think of the ring and it had remained tagged and sealed in an evidence bag along with the clothes Amy had been wearing and the barrettes from her hair. Prosper had found the ring along with the other things when he was closing out the case, slipped it from its bag, and after a moment of thought, dropped it into his pocket. He could not have imagined the heaviness of that small band of gold. He felt it whispering to him on his long drive, but he didn’t turn back. He couldn’t now. They say the dead don’t talk, but Prosper knew that wasn’t rightly true. The speak to us every day. A piece of ribbon, a quilt of calico and velvet, or a tin soldier can hold the weight of a thousand conversations past and others never completed. But it wasn’t memory and regret that drove Prosper on. It was certainty.

Prosper had seen things in his life that he could not explain. He didn’t let them worry him much. Life was filled with mysteries, and God had not made men to understand them all. Still he knew of a man who understood more than most. He was, what country folk, called uncanny, and what Prosper called a witch. There was a time that Prosper hadn’t believed all the talk about Old Man Everett, but that day was long past. He’d seen with his own eyes what the man could do. Here was a man who could wake the dead and put them to rest. Whether it was right or wrong Prosper didn’t know. It was probably best for men not to meddle in such things, but here he was with a cold ring in his pocket and a mind full of doubt. And ahead he could see Old Man Everett’s cabin and he knew somehow that the old man would be waiting for him.

The Old Man was sitting still as a statue in his rocker. If the moon hadn’t been high, Prosper mightn’t have seen him. He was a shadow in the darkness with only the lit end of his cigarette to betray him when he took a long drag. Prosper shut the truck door and the song seemed to linger on the night air. It took him a long time to walk to that porch and all that time the Old Man said nothing. But when Prosper reached the steps, he stood and ground out his cigarette.

Prosper stood staring at the Old Man for a long time and then said, “I reckon you know why I’m here.”

“Reckon I do,” he said, “I conjure you think you did me a favor.”

“I never did you any favors,” Prosper said, “That I do know.”

“I guess not,” the Old Man said, “But all the same, here you are, with that girl’s ring in your hand.”

“You don’t miss much,” Prosper said.

“I don’t miss anything,” the Old Man said, “Leastwise nothing that happens in this Valley. I make it a point not to.”

Prosper held out the ring, a simple band of white gold, and the Old Man took it and held it up under the light. “A thing of blood and bone,” the Old Man said, “That’s what this is. You want me to call that poor girl from her rest for this. For a truth you already know.”

“I don’t know,” Prosper said, “That’s why I’m here. If I knew, if there was some way to know, then some son-of-a-bitch would be in the jail.”

“You know.” The Old Man said, “And that’s why you’re here. If you didn’t know what this was, then you wouldna drove up here in the dark with the weight of a dead girl hanging around you like a storm.”

“Alright then,” Prosper said, “I do know what it is — murder, plain and simple. But I can’t prove it. The coroner and the law have ruled it natural causes, but you and I both know there’s nothing natural about it.”

“That’s so,” the Old Man said.

“So, you’ll do what you can?” Prosper asked.

The Old Man hesitated then nodded. “I will for the girl and for you and because there’s a law for these things as well. Though, like all laws, it can be broke.” The Old Man reached for another cigarette and Prosper could see his hand was steady as a tone. “I could tell you what you need to know,” the Old Man said, “But I reckon you need to hear it from her own lips. You didn’t drive all this way in the dark to talk to me.”

Prosper nodded and the Old Man held out the ring to him. “There’s some that might need such a thing, but I’m not one of them,” he said, “The Dead come when I call whether they like it or not.” Prosper took the ring and sat down on the stair while the Old Man lit another cigarette. Everett took a drag and said, “Filthy habit. I quit near on thirty years ago, before my Boy was born, but I found I had a need to the things again. You can quit and start many a thing if you live long enough,” he said, “Life’s a long path and a winding one.”

The old man picked up a twisted ash cane that was leaning against the railing and set to drawing a circle in the dirt, every now and again stopping to flick ash into the red soil. After a few minutes he stood back, took a look at the circle and then crushed out the rest of his cigarette on edge of the thing. He stepped into the circle and then said some words that Prosper later couldn’t remember although when he thought back on the moment he thought he had felt the words more than heard them. They were great, slow things that cut through the air like water through stone. There was a crack like lightning striking a tree and then Prosper could see a figure coming reluctantly up the dirt path like it was being pulled by wire. The shadow twisted and pulled but kept coming forward while the Old Man stood impassive in the circle looking down the road. After awhile he moved his hand and the figure sped up, as if he was a fisherman reeling in his catch.

Finally, the girl stood before them on the outer edge of the circle looking as she had the day they pulled her out of the Pond. Shoeless, dressed in a dark skirt and a pale blouse, she stood wringing her hands and looking back toward the way she’d come. “We’ll let you go soon enough,” the Old Man said, “Only this fellow has a few questions to ask you. I reckon you know what they’re about as you know who he is. There’s no getting away from the law,” the Old Man said, “Not even in the grave.”

The girl scrunched her face like she was about to cry, but said nothing. After a while she nodded and the Old Man said, “Ask your questions then.”

Prosper stood and started down the stairs toward the girl. He knelt in the dirt in front of her with his hand in his pocket wrapped around the ring. Finally, he held it out to her. “I never meant to take it,” he said. The girl reached out and plucked the ring off his outstretched palm. The moment she touched him, Prosper felt a light shock and smelled lilies and fresh spring dirt. The girl smiled and put the ring on her finger. “You left it on the table,” Prosper said. And, after she had nodded and held her ring hand up to the light admiring he asked, “Why?”

The girl who had been Amy Green wrapped her arms around herself and shivered though the air was warm. “I never meant to leave it,” she said, “I never meant to go. But it was always in my mind, every moment of the day. I could feel it even in my sleep and, in the end, there was no other way to get away. I never asked for it. I never wanted it. I prayed and prayed and prayed, but it just wouldn’t stop and in the end it was the only thing I could think to do.”

“What wouldn’t stop?” Prosper asked.

The girl looked sad and looked away. “He’s not a bad man,” she said, “I can see that now. But I didn’t love him. I told him I never would, but he just kept at me. At first there were notes and flowers and later I could hear him whispering in my head, “Love me, love me, love me.” But I didn’t. I would’ve if I could just to stop the whispers. But it just wasn’t in me. I thought he would give up after the wedding, but he didn’t. He just kept whispering until it was all I could hear. It was the worst at night. But it was there all the time. All the time,” she said and shivered.

“Who?” Prosper said and she gave him a name.

The Old Man moved his hand, but the girl didn’t move. When the she whispered, “You should have saved me,” Prosper blanched til he saw she was looking at the Old Man.

“I could have,” he said, “But I didn’t. There’s no malice in it. I was occupied with other things. Mostly with feeling sorry for myself. I let things slip that I shouldn’t have and you were caught between them.”

The girl nodded and started down the path and Prosper watched her until she was gone. Behind him, the Old Man said, “I won’t make any excuses. A man has to bear his burdens.”

“I can’t understand it,” Prosper said.

The Old Man just shook his head and sighed. “Don’t see why not. You’re a smart fellow and a witch is easy to understand. There’s one thing all witches have in common — they’re folks that just can’t let well enough be. They kick against the pricks instead of just letting them slide. They’re meddlesome. Could be some think they’re meddling for good. Others have a mind only for themselves or maybe they don’t think much about it at all. But at the core of it is a great want, a great emptiness that they can’t quite fill. Lots of men have it. Some turn to drink, some turn to religion, and others turn to witching. Once you start down that path, there’s no end to it. There’s just the need and that little whispering voice in the dark that says “Just one more.” But it’s never just one more drink or prayer or spell. In the end, the only way any man can stand is on his own two feet. The rest is just cowardice.”

Prosper didn’t say anything for a long time and then just as he was about to speak, he decided better of it. “That’s right,” the Old Man said, “I should know. But knowing doesn’t make you stop. Maybe it only makes you more arrogant. I’ve been where this fellow is. I’ve walked in his shoes, and he’s not going to stop, not anytime soon anyway.”

“You’re not a bad man, Everett,” Prosper said.

The Old Man said nothing. He turned his back and walked a little down the path and then he stopped. “You see that moon?” he asked. It was hard not to see. It hung full and low and orange-red in the sky. “That’s a harvest moon,” he said. “There’s a harvest moon and a wolf moon and a cold moon each year, but not like this. This is a true harvest moon full of bitterness and blood. Because, it’s been my experience, that’s the only real harvest there is in the end. The path may be long and it has many a turn, but in the end, we all end up in the same place.” He turned back on Prosper and twisted his walking stick in the dirt, “I’m tired,” he said.

Prosper knew that he was though no one in the Valley knew just how old. Even the grannies who sold herbs and dumplings in the market on fair day called him the Old Man. Some claimed that he was older than the Valley itself. But men are prone to telling tales around a wood stove with a bottle of whiskey passed hand to hand. No one lived forever.

“That’s right,” the Old Man said as if he’d heard Prosper thinking. “There’s not a fellow save Elijah who never died though there are words to wake the dead. This is an old magic called up out of the dark places of the earth. It has no name and the words are as old as the flickering of flames, the churning of waters, and the fiercest of storms. They are built into the fabric of things. Men were never meant to hear them, let alone utter them. They are the words of God. But men are curious creatures prone to meddle where they shouldn’t. Some say that fire was God’s gift to man, others that man found it, and others that it was stolen. But of these words there can be no debating. They were given. Spoken to raise a man. Once heard, they can never be forgotten. They burn and whisper in dreams. They’re hungry words. The only way to be free of them is to give them to someone else and until you do, you’ll never die.”

The Old Man stopped a bit and stared up at the moon. Prosper stood as still as an oak uttering not a sigh. He had a feeling the Old Man had never told this story before, not even to his son, maybe especially not to his son. There was a wait to his tale that bore on the air and made Prosper feel, for a moment, as ancient as the stones and as weary as the Old Man himself. The Old Man turned his back to Prosper and stood looking at the moon for a long time and then he spoke, “Most men think that immortality is a wonderful thing. But men weren’t built for it. It’s hard enough to live and love and hate all in a span of three score and ten or twenty or thirty. After that, a man starts to go ragged around the edges like a piece of cloth too long in use. He starts to think that those words that he begged and bargained for weren’t a gift. Maybe they were a curse. He starts to remember the way the fellow he had them off of smiled and sighed when he whispered them in his ear, and that when he crumbled slowly into the red dust the look on his face hadn’t been one of despair, but one of desperate relief.”

Prosper said nothing only waited and after a while the Old Man continued, “Of course a man of twenty or even twenty and ten doesn’t notice things like that. But they stick in the mind’s eye and creep up on you years later so that the last thing you see when close your eyes is the look on that old man’s face — a look so full of hope and peace that you long for it. You look for it in the mirror each and every day, but all you see is tired eyes and a bitter scowl because you know deep down in your bones what it means to pass the words along. You know what a horror it is to live through the ages, but you just can’t bring yourself to do it. Not because you’re afraid, but because you’re afraid of being that cruel to another living soul.”

The Old Man turned back to him then, “You may think you know a thing about cruelty, Sheriff. But you surely don’t. A good man may think he can understand such a thing, but he never can.”

“All men sin,” Prosper said.

“They do,” said the Old Man, “But only one with a good soul would admit it.” He waited a minute or maybe ten and then he said, “We best be going while the moon’s high. Tonight is a night of power, for him and me. If it’s to be done, then we best get to it. He’ll be waiting by now.”

“Why would he?” Prosper asked.

The Old Man looked back and his smile chilled Prosper to the bone, “Because,” he said, “He knows just as plain as you and me that there’s only one way for this story to end.”

The Old Man walked and Prosper followed. The air was heavy and damp like it gets sometimes in early October right before a storm. Prosper could hear the Old Man breathing heavy and sometimes he leaned hard on his cane, but in the end, they came to the grave yard, as he knew they would, and he could see a man standing with his hand on Amy Green’s grave. Even from this distance, Prosper could hear him weeping big ragged sobs and every now and again he’d strike the rough-cut granite with his fist.

“I didn’t mean it,” he said.

“Doesn’t matter,” Prosper told him, “What you meant and what you done are two separate things. She’s dead all the same and none’s to bring her back.”

The Boy looked at the Old Man with hope, “You could,” he said, “I know you could.”

The Old Man shook his head, “I conjure I could,” he said, “But I’ve tried that before and it never turns out the way you’d hope. Might be this time that she’d come back the same sweet soul she always was, but maybe she wouldn’t. Like as not, she wouldn’t thank you for it. She’s at rest now. Let her go.”

The Boy knelt and wept and after a time he pushed himself up and wiped his eyes with the back of his fist. It left a smear of mud beside one eye. “I only meant to make her love me,” he said, “It’s all I wanted. Just for her to love me like I love her.”

“You can’t push a thing against its nature, son,” the Old Man said, “Sometimes you can bend it for awhile, but sooner or later it will snap clean in two.”

The Boy nodded and started to weep again. “What will happen now?” he whispered. To Prosper he looked pitifully young, and, he supposed he was. But young or not, he still had a death on his hands, and sorry or not, he had to account for it.

The Old Man looked at him hard. “You knew what you were doing when you did it and damned the consequences. You only cared for yourself and maybe you should have a taste of the same medicine for surely there’s not a court made that believe the truth of it.”

The Boy kept on sobbing. Looking at him standing with his hand on the grave and the other against his chest, it was easy to forget that he had one death already to his name. One anyway that Prosper could lay at his feet. It would be simple to forget except for the empty space in Prosper’s pocket that kept reminding him. The weight of the ring was even heavier now that it was gone.

”He’s young,” the Old Man said, “There’s some that might say that given time, he might change his ways.”

“And, what would you say?” Prosper asked, “What do you think would come of such a fellow with time.”

“Likely, more dead folk,” the Old Man said, “But I been wrong before. And, I’ve never taken it on myself to be the judge of another man.”

“Maybe that’s just the problem,“ Prosper said, “Maybe you ought to have at one time or another. “

“You wouldn’t be the first to say so,” the Old Man said, “But that would make me no better than this Boy and we both know that love and pride have led me down roads I knew better than to take.”

“I been doing this a long time, “Prosper said, “Some days, most days lately, I think too long. It’s not the place of the law to judge a man’s right or wrong, just to gather the facts. And, I reckon, we both seen what’s true tonight, though no jury ever will.”

The Old Man nodded. “You done your work, Sheriff,” he said, “And, whether you believe it or not, I do owe you a debt. The laws that govern my kind are old and when a man decides to buck them, there’s a price to be paid. There has to be a balance to things and even if that black-haired girl laid down the coin this fella was owning, that doesn’t make his debt paid in full. Go on home, Sherriff. I’ll see things put as right as they can be.”

Sometime during the conversation the Boy had started listening to them and he now stood still and wide-eyed in the moonlight. Prosper almost felt some pity for him. Almost. He turned his back then and walked back down the path and, after a while, a cloud passed over the moon and all was dark save the moon and the stars. It was a long walk back to the Old Man’s cabin and a longer drive back to Prosper’s own home. He didn’t mind though. He was in no mood to face sleep. He thought some day he might have to ask the Old Man what became of the Boy, but maybe he didn’t want to know. There were truths in this world too fearsome for a mortal man and mercies too terrible. Maybe it was enough to know that his was not the only law and that the Dead could forgive you. Or maybe it wasn’t.

On Stories

Stories are living things. They want to be told. It’s the way they grow. Each time you share a story, it changes a bit. It becomes a part of the storyteller and the listener. A good story may stick with you for a lifetime, and a good ghost story never stops haunting you.

I’ve collected stories all my life and in my line of work I’ve been lucky enough to meet many people with a passion for a tale well told. There is, after all, no greater pleasure that sitting in front of a fire, with a warm mug listening to someone tell a story that chills you to the bone. Those are the stories you remember. Those are the stories that you pass on.

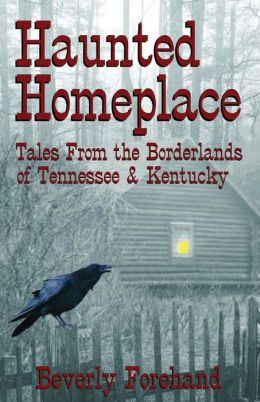

If you enjoy Southern Gothic ghost stories and you’d like to support my habit of books, boots, bourbon, and cats, then you might want to check out my book, Haunted Homeplace: Tales From the Borderlands of Tennessee & Kentucky. You can find it on Amazon.com and at Barnes & Noble.

I hope you enjoy my stories. Most are about ghosts, some are about the supernatural, and all are about the South. Take them, make them yours, pass them along, and maybe I’ll hear them again sometime, slightly different, but always the same, around a campfire.

If you want to check out my other stories at Bewildering Stories, just click on my Author’s Page.

Copyright © 2014 by Beverly Forehand