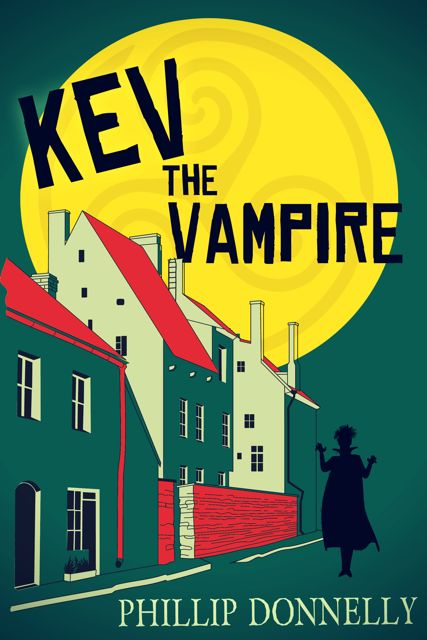

Phillip Donnelly, Kev the Vampire

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

Kev the Vampire Publisher: Rebel ePublishers, 2014 Length: 394 pp. ISBN: 0692329161; 978-0692329160 |

When I was in the eighth grade, unbeknowst to my father, I forged into the adult section at my local library. Although my teachers complained on my report cards that I was too quiet in the actual classroom, underneath the meek, I was a brassy bold adventuress. I feared nothing on the printed page.

Two books, though, knocked my youthful cockiness right back on its heels. One was Jerzy Kosinski’s horrifying The Painted Bird. That one taught me the necessity for age-appropriate self-censorship. I lay awake for nights with the horrifying pages perfectly visualized in front of my eyes. It took me weeks before that terrible eidictic recall went away. I read De Sade in later years with far less trauma than that book inflicted on me then.

The other ego-smasher was Finnegan’s Wake. Somewhere, I’d heard it was THE most difficult book ever. Hah, my juvenile self smirked. Maybe for the dingle-heads — I meant my classmates; I was an arrogant little twerp at that age — not too hard for me. Sound the idiot buzzer! I tried it. I did not get it. Stumped and smarting!

But after all these years, I still have two clear impressions of that book. The first was a weird sense that the settings were like the fuzzy images I saw when I took off my thick glasses — well, high-prescription contact lenses, actually. Thank goodness! Is that dim, distorted image coming through the prose a bridge? Hey, did we just cross a river there?

I’ve since concluded that unless you intimately know the setting of Joyce’s book, you’re wasting your time with Finnegan’s Wake, that Irish writers, in general, are almost too intimately connected to their native soil and really most comprehensible to the rest of us when they’re forced into exile. Distance is actually good for their art.

The second impression was: Joyce wrote like a bravura pianist banging out Scarlatti with his left hand and Chopin with his right — at the same time. The man was drunk on his own gift of glorious words. In love with his prose, carried off in flights of glory and raptures to psychedelic heights no mere reader could ever follow. In fact, readers need not apply. The ecstasy of prose reaches its own masturbatory high for its writer.

Phillip Donnelly’s blackly comic Kev the Vampire fits right in there with Joyce: the rhapsodized love affair with its insiders-only Dublin setting; the narcissistic flights of words, divine words. As it happens, almost everyone in the book is a failed but fervent writer.

The surrealist triporama begins at its end, with said teenager Kev in the loony bin, convinced he is Dracula. In the course of trying to unravel the threads of their patient’s madness, Kev’s psychologist and his teacher follow the same path and meet the same doom. What doom do they suffer? Modern urban misery and narcissistic flights of escapist fancy have a fatal collision with the unfortunate Self squished between. Xanadu — or, rather, Transylvania — must look better than Dublin.

Skip the author’s foreword. Authors should resist the temptation to explain their works to dim-bulb readers. That mistake is made worse when the author’s explanation isn’t really what the book is about.

What comes out of an author’s head is part conscious and part subconscious. And we’re not always aware of what rises to the surface from those deep, hidden pools. So try not to write your own forewords until plenty of others have had their say first.

Readers who prefer to avoid graphic language and over-the-top blasphemous imagery should be advised Kev the Vampire has both.

Donnelly is a Bewildering Stories contributor, and we’re glad when one of our own gets the novel out here. Congratulations, Phillip!

Copyright © 2015 by Danielle L. Parker