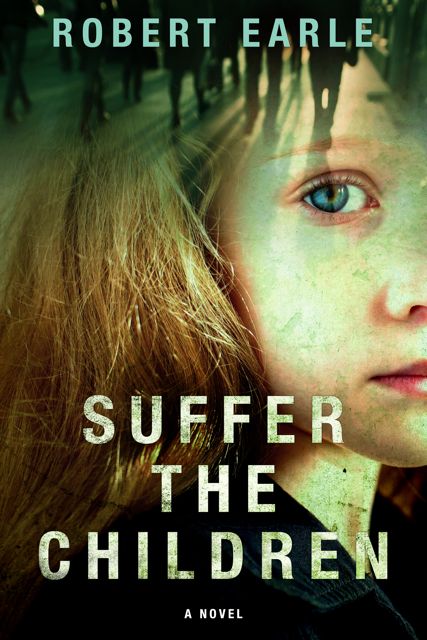

Robert Earle, Suffer the Children

excerpt

Suffer the Children Publisher: Vook Publishing, March 2015 Vendor: Amazon e-book ISBN: 9781681059228 |

Synopsis

Reigniting her notorious affair with disgraced General Budge Kleeforth, Pru Malveaux urges that he redeem himself by devising a way to protect school children from lethal assault, such the one that occurred in a town close to Glenwood Park, Connecticut, where Budge grew up.

Gun lobbyists fear Budge’s ingenious plans to counter their products. With connections as high as the Vice-President, they conspire to destroy Pru and Budge’s renewed liaison and buy out their project.

Meanwhile Glenwood Park’s teenagers believe they ought to be able to identify the next assailant through their knowledge of community secrets, not anticipating the effect of their cynicism on someone in their midst.

The arms industry’s plot threatens Pru’s ulterior motive--regaining custody of her own two children. She unintentionally drives Budge toward a young schoolteacher they have been training and discovers that her actions have cost her everything.

When Suffer the Children’s multiple story lines collide, the ensuing tragedy raises the question: If the arms industry can keep the nation’s guns safe, how is America going to keep its children safe, too?

As a general, Budge had not traveled alone for many years; he always had staff: at least one officer and a sergeant, as well as three personal security guards for consecutive eight-hour shifts. That was his package on civair. Milair it could be twenty or thirty to give more people a chance to come into his cubicle and go over things.

Everyone conformed to his schedule. 4 AM wake up; 4:30 AM workout; 6 AM breakfast; meetings beginning at 7AM; reading time from 11 to noon (and 6 to 7 PM); lunch at noon; the second workout if possible at 3 PM; meetings before and after the second workout; phone time 4 PM to 5 PM; light dinner inside at 7 PM or some caloric disaster outside; more phone time afterward; then 10 PM to bed, dead man falling.

In Budge’s view a warrior’s objective was to go 95-98% forever. If he had to attend a party or an awards ceremony or even a morale exercise (watching a basketball game on a big screen with some guys), he treated them as meetings, all of which he ended with three notes: 1) what did I learn? 2) what was the outcome? 3) was the outcome worth the time and effort? His instruction to his staff was to make sure these questions could be answered positively or else don’t schedule a meeting or an event or somehow push it to rise to standard-include more people, distribute a pre-brief questionnaire to get people on their toes, or simply advise that if the general wasn’t going to learn something and see a positive outcome, then go see someone else.

He was 28 when he acknowledged to himself that Katie was staff. Katie probably understood that when she was 21. He wanted 3 kids; she produced them. He wanted a spotless house; she produced it. She managed their money and looked after everyone’s health. When he was simultaneously working at the Pentagon and earning his PhD, she would occupy the kids full-time and do things like take them to Disneyland or Six Flags by herself. You could not marry a better woman, but you could not sustain a marriage when married to someone as programmed, worn-out and subordinated as Katie. She had no time for exercise, watching what she ate, reading, or just doing things with him. He didn’t just do things. He stopped that the day he went to West Point.

Budge lived with this realization for the next 20 years. He needed and depended on Katie but he didn’t love her. In sex he was quick on and off. He kept his eyes averted when she was getting dressed. Many times he told her they were moving (36 times) on the phone or in a note, not face-to-face, and if she wanted to take the family up to Glenwood Park to see her mom and pop, he did his best not to go along because that would mean he’d have to bring his own mom and pop over to her place to pay court to the great man, mayor of Glenwood Park, a guy who liked to tell Budge, over and over again, how lucky he was having caught Katie, making Katie giggle like she did when she was a teenager. In fact, Katie’s dad wanted Budge to retire from the Army and run for mayor of Glenwood Park himself. The problem for Budge wasn’t the huge step down from being a general to becoming a small town mayor; it was the supposed upgrade he’d experience coming from his rank and career to assuming the mantle of the family into which he’d been lucky enough to marry. Budge’s father, Otis, was a bookkeeper for three local drug stores; Budge’s mother was a librarian in the school system, and not the head librarian. West Point was the best thing that ever happened to Budge and his family because it was free, but would Budge have gotten the appointment without Katie’s father’s intervention with the congressman at the time? Katie’s father doubted it. “You picked the right girl to get sweet on,” Katie’s pop would say, meaning, of course, Budge had picked the right father-in-law if he wanted to make something of his life.

Budge went into special forces, then combined ops, then tactics and weapons, then joint command rotations, then force training, and then combat followed by the training command in Iraq and the lateral over to Afghanistan with no promotion because foreign force development wasn’t a four star posting.

Pru visited Iraq a few times on a research grant from a war and peace institute at UNC and eventually got his attention because she knew so much more about Iraq than his intel staff. She had the bigger picture, the deeper insight into the tribes, the regions, the Sunni-Shia split, the evolution of Saddam’s regime. If you wanted to talk about the role of the religious hierarchy in Najaf, she could do that. If you wanted to talk about what she called “Euphrates” culture, she could do that. Mosul, that. The western reaches of Anbar Provinces, that. Syria, that. He was annoyed with himself and his staff that they were fighting a war without understanding what they were doing as well as an adjunct UNC academic who wasn’t active duty anymore. She was an historian, odd major for a West Pointer, and she was really an historian. Remember, she’d say, irritating everyone, the past becomes the future before the present can blink. She was the one who validated his belief that a few guys in Iraq working on local scales could capture the deeper dynamics of the place, and that success to the extent possible would come from relating Iraqis to Iraqis and not Iraqis to Americans.

“Talk to me,” Budge said to her one afternoon in his office at Camp Victory outside Baghdad.

She returned to the era of Mohammed and spun a tale from that point forward in which the entirety of the Middle East was neither an assemblage of what we call nations, nor a system of states, the Ottomans notwithstanding. “Sovereignty in our sense is an entitlement of a people. Sovereignty in their sense is the subjection of a people to a king or tribal leader, who can be considered a sub-king to Allah. Sovereignty in our sense has a geographical beginning and an end. Sovereignty in their sense is limitless until proven otherwise.”

She knew Arabic and Islam and ancient history and the political history post-WWI. In a way Budge began to feel stuck with her the way you feel you’re stuck when you’ve got to hurry up and do a job but there’s someone telling you to stop what you’re doing because you’re doing the wrong thing.

“Do more politics and less fighting,” she said. “You know this is true, you’ve written it yourself: Everything will improve if you give them an incentive to take on what you oppose for their own reasons and then get out of the way.” She was self-assured and cool, far cooler than Budge who had never been cool in his life. Wore tight fatigue pants and tight T-shirts and desert boots and a ball cap. No insignias. She’d given insignias up when she’d resigned her commission and gotten married, but look at her. She was in her element. She was happy. She was as fit as anyone, and it was as though she understood him perfectly: You became a monk without intending to; you know you shouldn’t be happier in the field than at home but home is worse, including a wife you don’t love who doesn’t understand your intensity.

She came through Iraq a few times, and then he was transferred to Afghanistan and worked like the devil, becoming a tired man who welcomed the opportunity to give a talk at Chatham House in London. So tired he wanted to just go there alone and say what he had to say under the Chatham House Rules, which were sacrosanct: you said what you had to say and no one repeated it (more or less).

As he transited Dubai, the staff he left behind looked at him like abandoned animals. Who would feed them? What would they do? He said he’d been through London so many times it was like a second home to him; he didn’t need anyone. What about security? He said he’d fought in three wars now and could take care of himself. He’d wear a baseball hat as a disguise, how about that? His old Yankees hat. Would he wear his kevlar undershirt? He said it depended, but kevlar might be just thing for a stroll through Hyde Park in October. He really wanted to be alone. He was whipped. No gas left. Stalled. Battery dead.

Now Pru was a visiting scholar at Chatham House working in conjunction with a NATO cell supporting IFOR in Afghanistan on multinational special ops. At the opening reception she said she was working hard to learn as much about Afghanistan as she could.

“I’ll bet you already know more than me,” Budge said.

“But, General, you’ve been there ten months.”

She was by far the most attractive woman in the room and that’s what triggered his response, personal in nature, sidestepping all he knew about Afghanistan, which was a lot. He’d been everywhere, high and low; he’d seen depthless beauty in the northeastern mountains and staggering wastes in Baluchistan, the eyes of murderers, cowards, and bullshitters, the lassitude in an Afghan recruit’s posture the instant he donned a uniform, and the skeptical, haughty expressions of Afghan leaders, including some women, who somehow conveyed sorrow that such a man, such an army, such a country, should lose itself like all the others in the pursuit of one grain of honesty that would stay stuck to another so that a poor foreigner would have something to stand on, two grains of sand, and not slip, fall and fail.

“Is that how long since we’ve seen each other?”

She said, “Yes, it is.” As if she’d been counting.

“I didn’t know you’d be here.”

“I was excited to hear that you were coming.”

He wasn’t in uniform, to be discreet, and she wasn’t either, but indiscreetly so. She wore a dress that knotted behind her neck and exposed her shoulders. Her rich chestnut brown hair was pulled up tight and drawn into a chignon in the rear. The peculiarity of speaking to someone so elegant and so intelligent made him think, briefly, of Katie and the incongruity of Katie becoming a stout middle-aged woman while he relentlessly maintained the same body he’d had since he was 22.

Of course he looked at women. Men never stopped. But he had a peculiar means of evaluating come-ons. Would this woman attempt to seduce him if she knew him as Katie knew him? If not, and usually not, what the woman wanted was not the real him. He was celebrated too much; he had claimed too much glory that wasn’t his; he had made a lot of mistakes, especially in Iraq, that he would want no one to know about, deals with sheiks that he regretted. In a way it could even be said Pru had made him less appealing to himself by being so smart, a woman who, if she’d known him as a boy, would have reached for another dish.

“Oh, I’m just bringing the usual canned Spam,” he said. “These conferences . . .” He didn’t finish his sentence.

“I know but for now it’s as close as I can get to what’s really happening.”

“You mean in Afghanistan.”

“I mean in Afghanistan.”

“What would you give to get yourself to get a TDY there?”

“Anything,” she said without hesitation, her brown eyes large and enveloping. “I already have read a mountain of books, and there’s a professor at UNC, an old fellow, who’s teaching me Pashto.”

Budge said something to her in Pashto. She replied in better Pashto than his. Then they laughed because it was silly; neither of them would ever get any good at it. Who had Budge laughed with recently? He couldn’t recall and had another glass of champagne and finally realized they’d have to stop talking to each other or people would notice.

Chatham House paid for his lodging, and he’d asked if it could be a hotel of his choosing, a place called Queen’s Gate Suites. Out of the way. A favorite place of his. All through dinner he debated with himself. He knew that if he invited Pru to the Queen’s Gate Suites for a post-event drink, she’d agree. She was married, he was married, didn’t matter. The idea that he might not suggest it probably never occurred to her. That laugh; that smile when they parted ways to talk to other people. How she dressed. How she let her eyes rest on him light as feathers. He was used to hard things, not soft things; resistance, not yielding. She’d tease him if he tried to explain that his driven asceticism was essential to him; it was him; if he let it go for an instant, what would happen to him? Women did not believe that any higher order or calling ever trumped a man’s lust. They didn’t believe it with priests, why should they believe it with soldiers?

He figured out a half step. After the dinner he asked her if she’d like to take a stroll with him through St. James Park and have a nightcap at a bar he knew. She said she’d love it. It was a chilly, misty evening. She slipped her arm through his immediately.

“Gosh, it can be so cold here, can’t it?” she said. “Feel my cheek.”

He felt her cheek with the back of his hand, not the fingers. It was soft and cold and enticing. He turned his hand over and pushed his fingers into her hair, tracing the shape of her lovely head, just grazing her ear.

She laughed the way you laugh when something is too much. Stop now. She hugged his arm a bit tighter.

“Feel mine, too,” he said, meaning his cheek.

She shook her head, not taking the bait. In his taupe overcoat and Yankees cap, he resembled neither a general nor a London dandy, more an eccentric gentleman on a visit from the country for whose pleasure she was somewhat overdressed, thinking me, you, London, the silvery mist, the steady traffic and eye-catching shop windows and yellowish street lights barely scraping the sky’s low ceiling. She’d felt an urgency about him two or three days after she arrived in Baghdad, having seen him conduct a meeting, the way he questioned people, the sense he gave that when the meeting was over there would be a smaller meeting of intimate advisors gathered in his office. He was attentive but not committed to what he heard in the large meeting; resolutions would occur quickly in the smaller meeting. She wanted to get into that meeting, and she felt she could do it. She’d slip in, she’d go to the map, and she’d point out that someone in the larger meeting had said a certain place was northwest of another place, but it wasn’t, it was due east, and there was a desert/river cultural division in that place between how the adjacent tribes behaved. The desert tribe retained a loyalty to insurgent resistance. Meanwhile the river tribe tended to look south and wished it could get back to the life of fishing and shipping and the ancient formalities of courtesy, respect, and deference because the river was the river and could not be revised by taking a different route the way the desert-oriented tribe could could revise the sandy wastes however they wanted. She didn’t have to go into all that. She just had to say that someone had misspoken: east, not northwest. And then confuse things by being a beautiful woman not in uniform who nonetheless was a West Point graduate whom someone would have to introduce to the general who then, if she were lucky, and she was, might invite her to sit down.

The club was attached to the Queen’s Gate Suites. Their affair began upstairs. What mattered, initially, was the satisfying shock and pleasure of a new partner, in neither case a commonplace or anything trustworthy, likely to crumble with the dawn, but when dawn came they were still talking. She told him about herself-her frustrating decision to go into the dead end of military history because it would make her marriage to an Army doctor more feasible (fewer or no deployments; he could intern and do his residency at Walter Reed and she could spin out as necessary into research or just put up with Pentagon assignments)-and the problem posed by his life, which was now centered at the medical center in Chapel Hill, neither of them commissioned officers anymore, him in the Reserves, she not even that, a UNC adjunct who flirted with teaching at the Citadel and at VMI but they had two kids. These overseas stints she engineered were the best she could manage for herself until . . .

“Until when . . . ?” he asked.

She swung over him and began making love again instead of answering, pressing herself against him and then drawing up so he could see her breasts, her hair loose, the way she smiled when she saw him start to lose it.

What he liked were their dates and rendezvous not just in London but in D.C. and New York and Amman, their intimate emails, their conniving to have her dispatched to Afghanistan where she spent more time in his headquarters than in the historical unit. The guys in the historical unit just gave up on her.

His proposition was that he wanted her involved because she had one of the best strategic minds he’d ever encountered. An historian? Yes, but the truth was she did have a fine mind and she did work like a demon at Af/Pak Issues, and something came up that he felt required a unique if risky maneuver. There was a presidentially appointed Af/Pak coordinator Budge despised whom he thought Pru could handle, acting as both liaison and spy despite the inevitability that this guy, Sandy Markham, would try to seduce her away both physically and intellectually.

She didn’t like the idea at first, but it just made sense. “You’re the person I trust most in the world,” he said, “and Markham could be the guy I trust least. He spends more time in the back channels than a catfish, has for decades. Big donor, big ego, big problem.”

“Budge, even his friends hate him. He manipulates everyone.”

He thought this through for several days. The question that disturbed him most was whether, out of fear of being exposed and wanting to just go back to the safety of marital eventlessness, he was putting her in jeopardy-putting them in jeopardy-as bait he’d like Markham to strip away. He felt he had one thing in his life that worked, really worked, but did he deserve it? Did she deserve what their relationship could do to her life? He didn’t feel comfortable with his decision to keep pressing, but he began to see the challenge flattered her.

“Maybe I can contribute something none of us can foresee,” she said.

“Maybe you can. I just know I can’t let the guy chopper back and forth from Kabul to Pakistan trying to make deals that are diametrically opposed to what we’re doing. He wants Pakistan to take over here. That’s obvious, but since when have we been able to trust the Paks? I need you engaged. I need you to be inconvenient, pointing out the historical odds against what he’s up to.”

She let slip, deliberately, “And people can speculate about me and him, not me and you.”

“You think they are?”

“Of course they are.”

She said that as if she liked it, but Budge didn’t. They’d been reckless; he realized that.

“Go on, then,” he said. “I’ll set things up with Markham. He’ll know exactly what we’re doing and do his best to turn the tables on us.”

“But I won’t let him,” she said.

And then she kissed him in that way he’d never been kissed. Had she been really naughty learning that? She wouldn’t say.

With Pru in his entourage, Markham, a large, whining man who laughed only when someone took a poke at him, bulled ahead demonstrating his cocky contempt, never stopping his meetings with the top leadership on both sides of the border whether he had something new to say or not. To him life was a game without rules you played hard and in your opponent’s face. Pressure was everything, make yourself an irritant, raise irrelevant questions and inflate them with phony importance.

Pru liked him the way you liked things in the reptile house at the zoo; his tongue was that quick, his fangs were that sharp, his scales were that armored.

“Which means you don’t like him at all?” Budge asked.

“Which means I find him despicable. He kicks people around, bad mouths them to their superiors, forces all of us to go places we really shouldn’t be.”

Oddly, this escapade brought Budge and Pru closer. Markham said Budge was a “wuss.” He pestered Pru to agree. Pru retorted that Budge was a decorated combat veteran with a PhD who’d reached general as fast as anyone in the history of the U.S. Army.

“But will he get his fourth star if he doesn’t see the wisdom of going big and fast in Afghanistan to make the Paks deal? I doubt it, no matter how deep he has you in his camp.”

“No,” Pru agreed, “I’m certainly not the one who makes decisions on giving out a fourth star.”

“But you could be,” Markham pressed. “You could turn Budge around. You could make him see going slow and small is stupid. I’ve got the the Hill on my side; I’ve got the Afghans chafing to get their hands on more loot; all I need is enough leverage to force the Paks’s hands and make them get serious so we can turn this meaningless hell hole over to them and go home.”

Markham would sit up until one in the morning talking to Pru, scheming, pleading, threatening, trying to turn her against Budge. When Budge listened to her reports, he wondered why she didn’t capitulate and kept asking himself if it wouldn’t be better that way. Lose her to Markham, create a scandal for Markham, not Budge. How else was this going to end? That they both divorced and got married? No, he doubted it. He couldn’t see himself letting Katie go yet here was the conundrum, here was the pain: Pru made him uniquely happy. When he saw her, he immediately realized he had something he wanted to say and no one he wanted to say it to but her. And then they would hoot at Markham’s propositions, which definitely veered toward sex.

“If I could get as close to you as Budge is,” Markham told her suggestively, “the two of us could end this war in six months. I could get you any appointment in Washington you want. The White House owes me for what I’m doing out here. Believe me, I tell them that every day.”

From that coffee incident as a plebe at West Point on, Budge knew that taking down enemies mattered. But he probably never had an enemy of Markham’s scale he disliked so much. One day Markham would take a new recruitment and training idea to the president’s office in Kabul, totally without clearance, and sketch it out, as he liked to put it, “conceptually.” And Budge would have to get over there and stop it. Or Markham would show up at a transit point en route to Kabul-Jordan maybe or Abu Dhabi-and accompany a congressional delegation on its last leg so that he could criticize Budge and all the other senior officers in Afghanistan.

The idea was that the congressmen would get off the plane convinced that everything on the ground was going badly because Budge wouldn’t help force the Paks to buy into an endgame. Knowing this, Budge would fly to Islamabad and be there, not in Kabul, when the codel arrived, thereby undermining Markham’s jeremiads about him not cooperating with the Paks.

Inevitably things got personal and dirty. Before he died in a chopper crash, Markham set the leaks in motion that would reveal Budge’s affair with Pru, putting it in the worst possible light: a senior officer exploiting a married civilian with two children under ten. Pru was in that chopper crash, too. It wasn’t enemy fire; it was bad maintenance, too much dust, heat, and use. Markham had pushed his pilots beyond their comfort level and good judgment.

Having survived with only a broken collarbone and wrist, Pru was sent back to Washington, checked into Walter Reed, and before she could be released, was confronted by her husband with the Washington Post: Diplomat and General at War Over a Woman: Markham’s Death Leads to Kleeforth’s Demise.

Copyright © 2014 by Robert Earle