William Hope Hodgson,

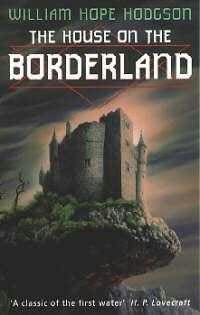

The House on the Borderland

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

The House on the Borderland Publisher: FrontList Books, 2003 Length: 174 pages ISBN: 1-84350-073-6 |

Like Hodgson’s The Night Land, lingering first impressions were powerful. Finding a recent re-issue of the book, I decided to re-acquaint myself.

H. P. Lovecraft later followed the same dead-pan this-is-real tone Hodgson first used. The House on the Borderland purports to be a diary found in an old Irish ruin by two vacationing fishermen. The ruin is situated in sinister abandoned orchards and gardens, perched on a lip of stone hanging over a deep chasm filled with a torrent. There is a scary lake, unexplained noises and jumpy vibes. The fishermen grab the book and make a run for it.

Let’s say right here Hodgson does spooky atmosphere as well as anyone, and the fact this book was first published in 1908 doesn’t make a bit of difference. The scenes played out like an old black-and-white horror film, creepy music and all. And frankly, for atmosphere and creepiness, the early ones were the greats. Later film creations confused blood-and-guts for creepiness, and I can scarcely think of a modern horror film to match those early ones for atmosphere.

Everything Lovecraft did later with atmosphere and pseudo-realism started here. Forget the occasionally Victorian prose and mid-story interjection of a romantic sub-plot in Hodgson’s story. No one conveys the existential loneliness of man in a vast, incomprehensible, creepy and evil universe better than Hodgson.

The diarist lives alone in the strange big house (which isn’t yet ruined), with his sister and his loyal dog Pepper. One day in his workroom, he suffers a strange cosmic journey that takes him to a remote plain surrounded by mountains. There in the empty plain of his vision, he sees an identical copy of his house in Ireland (only green, and much larger). The house looks empty and is shut and barred.

Weird mythological giant god-monsters surround the house from the mountain ranges, their gazes fixed on the barricaded house. Our bodiless visitor, the diarist, finds himself drawn toward the house. He encounters a hideous pig-man, also giant in size, attempting to force entry into the house. The pig-man becomes aware of him, and the diarist barely floats away in time to return to his consciousness and own house once again.

But all’s not well at home. The diarist finds a watery pit beneath a cellar trap-door. Rocks slip, the land changes inexplicably, and the little stream in a gloomy hollow outside becomes the great chasm and torrent of water later encountered by our two fishermen.

Human-sized pig-men launch an assault on the house. They want in, in both dimensions. The diarist barricades himself inside, fights the pig-men off (though they don’t seem able to die), and terrifies his sister, who doesn’t seem to understand what’s happening.

And things get weirder. Time slips, speeds up, and he watches his house decay around him, along with his own body. The inter-dimensional house takes him on more cosmic journeys. He sees the end of the solar system, dimensions that might be Heaven or Hell (did I mention Hodgson was the son of a clergyman?). In the end, he encounters the pig-men at “his” version of the house once more... and not so happily this time. The diary ends abruptly.

You won’t make sense of this book. The prose is sometimes difficult. It’s descriptive, not action-oriented. Doesn’t matter. For weirdness, scope of imagination, and creepy atmosphere, particularly that sense of terrible isolation and loneliness so peculiar to Hodgson’s works, this is the original, the seminal work. H. P. Lovecraft owes a huge debt to Hodgson, one he freely acknowledged. Download this book from Project Gutenberg and read it someday.

P.S. For another of my “classics” reviews, check out William Morris, The Wood Beyond the World.

Copyright © 2011 by Danielle L. Parker